This is the sixth article in an ongoing series. The previous parts can be read here: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5.

![]()

In rhetoric, the term “prolepsis” refers to giving something a name before that name properly belongs to it. In Genesis 3:20 it is stated that Adam “called the name of the woman Eve, because she was the mother of all the living,” even before the birth of their first child. (The name “Eve” and “life” are etymologically related in Hebrew.) Likewise, Genesis 14:14 states that Abraham pursued the captors of his nephew Lot “as far as (the city of) Dan”, even though the city was then called Laish, and only given the name Dan when the tribe of the same name seized it, as recorded in Judges 18:29.

The sacrificial language of the Offertory, “receive… this immaculate victim … we offer Thee, Lord, the chalice … receive this offering” is an example of prolepsis, referring to the Sacrifice before what is actually sacrificed is present, namely, the Body and Blood of Christ. The literal Latin equivalent of prolepsis is “anticipation”, and it was dislike of this anticipation of the Sacrifice that ultimately led to the radical overhaul of the Offertory in the Novus Ordo. Fr Aidan Nichols writes about this beautifully in his book Lost in Wonder: Essays on Liturgy and the Arts. (pp. 40-41; chapter 3 “Eucharistic Theology and the Rite of Mass.”)

There are many other examples which might be drawn from the Secrets of various Masses written in all periods. With them should also be included the very title of the Secret commonly found in the ancient sacramentaries, maintained by the Ambrosian Rite, and restored to general use in the Missal of Paul VI, namely, “Super oblata – the prayer over the things that have been offered,” where it might just as well have been called “Super offerenda – over the things which will be offered.” There is no warrant for imagining that the proleptic use of the past tense form “sacrificed” or any similar terms indicates a belief that the Eucharistic Sacrifice, or some other adjunct sacrifice, took place before the Canon. The presence of such language in the Offertory simply extends backwards by a few minutes a traditional way of speaking which has been almost universally a part of Christian worship from the most ancient times.

There is also, however, a broader meaning of the term “prolepsis”, which is given by the Roman rhetorician Quintilian in The Institutions of Oratory. (Book 9, chapter 2, 16-18)

For this reason, we find that in his Book of Sentences, the principle theology textbook of the High Middle Ages, Peter Lombard devotes but a single article to the question of the Sacrifice of the Mass. (Lib. IV, dist. 12.5) Both St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas Aquinas, in their commentaries on the Sentences (the medieval equivalent of a doctoral thesis), do not comment on this article, although they refer to it in passing elsewhere. Marshall describes the situation thus: “Thomas, it seems, does not so much deliberately ignore the sacrificial side of the Eucharist as follow an established pattern that does not see this as a problem needing special attention.” (ibid.)

On the other hand, prominent heresies about the Real Presence have arisen at several points in the Church’s history. At the very beginning of the Scholastic period, Berengarius of Tours (999-1088) caused a huge controversy by attacking St Paschasius Radbertus’ teachings on the Real Presence, an attack for which he was condemned, imprisoned and forced to retract. St Norbert, who founded the Premonstratensian Order in 1119, famously combatted and extirpated the heresies of Tanchelm, which included the complete denial of the Real Presence. In the following generation, St. Bernard identified among the errors of Peter Abelard “his opinion…on the Sacrament of the altar,” summed up as the ninth on the list of the latter’s heresies. (Epistle 188.2; cf. 189.2) Less than 30 years after the death of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Dominican John of Paris, considered by his contemporaries one of the greatest theologians at the University of Paris, tentatively proposed that belief in transubstantiation was not de fide, and put forth a theory of “impanation,” looking back to some of the ideas of Berengarius’ followers. In our own times, Pope Paul VI found it necessary in the encyclical Mysterium Fidei to reassert the Council of Trent’s teaching on transubstantiation, and reject by name the new heresies of “transignification” and “transfinalization”, as well as the proposition that “Christ the Lord is no longer present in the consecrated hosts which remain once the celebration of the sacrifice of the Mass is finished.” (parag. 11)

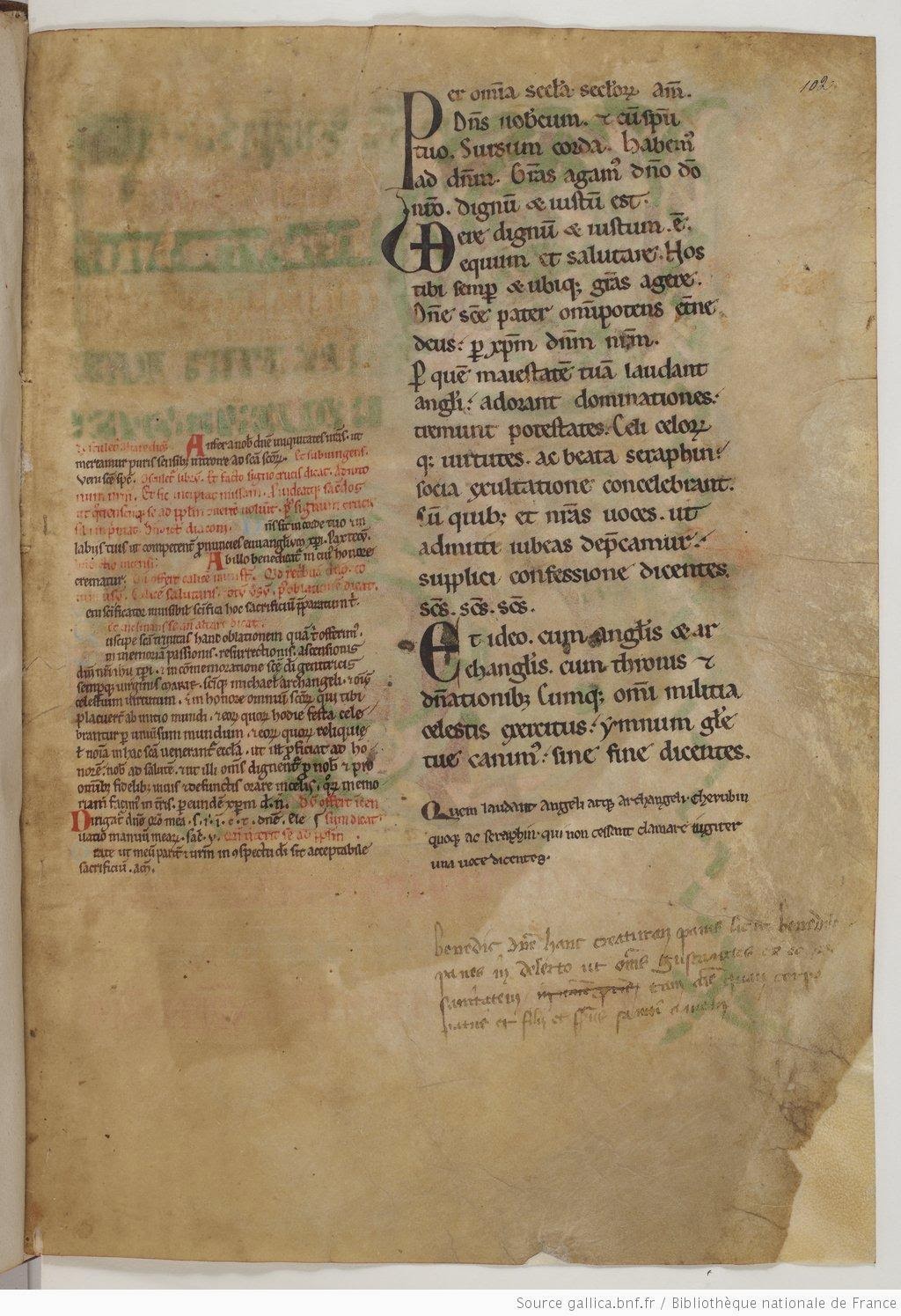

Now although the Offertory prayers predate the Scholastics, we may fairly say that their position in the liturgy of the Mass was consolidated in the Scholastic period, the era in which the missal would displace the use of the earlier sacramentaries, lectionaries and graduals. The medieval missals have various forms of the Offertory, some simpler and some more complex, but to take the most widely used example, that of the Roman Missal refers to “sacrifice” in various ways, but never uses the term “bread.” The most commonly used Offertory prayer Suscipe sancta Trinitas is found in many medieval missals that have none of the other Roman prayers, and also makes no reference to bread.

This constant use of “sacrifice” without “bread” is a prolepsis in the broader sense given by Quintilian; it establishes the proper meaning of terms, excluding in anticipation any idea that the liturgical act of offering offers bread. This declares in advance, against the many Eucharistic heresies past and present, what the Canon does not do. It is then left it to the Canon itself, the older part of the Mass of the Faithful, to declare right before the consecration what it does do, namely, make present “for us the Body and Blood ... of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

The sacrificial language of the Offertory, “receive… this immaculate victim … we offer Thee, Lord, the chalice … receive this offering” is an example of prolepsis, referring to the Sacrifice before what is actually sacrificed is present, namely, the Body and Blood of Christ. The literal Latin equivalent of prolepsis is “anticipation”, and it was dislike of this anticipation of the Sacrifice that ultimately led to the radical overhaul of the Offertory in the Novus Ordo. Fr Aidan Nichols writes about this beautifully in his book Lost in Wonder: Essays on Liturgy and the Arts. (pp. 40-41; chapter 3 “Eucharistic Theology and the Rite of Mass.”)

Though disliked by people with tidy Germanic minds, the anticipation of the Anaphora… is a frequent feature of historic liturgy. It is even more pronounced in the Byzantine Rite… as the dedicated bread and wine are transferred to the altar at the Great Entrance, the choir sings ‘Let us … now lay aside every earthly care, so that we may welcome the King of the universe, who comes escorted by invisible armies of angels’, even though that ‘King’ only ‘comes’ in the sense that the dedicated gifts are now brought in so that they may be offered in the Holy Sacrifice… to the worshipping mind of the Byzantine Christian they are, however, already images of the Lord’s body and blood, and, proleptically, the King does come with them, since he will come in them at the Consecration. Liturgical time is not ordinary time…The proleptic use of the term “sacrifice” and related concepts before the actual Sacrifice takes place is extremely ancient, being found first of all in the Canon of the Mass itself. In the Te igitur, the priest asks God “to accept and bless these gifts, these offerings, these holy, unblemished sacrifices.” (“haec dona, haec munera, haec sancta sacrificia illibata.” The word “munus” can also mean “sacrifice.”) It is also found in a great number of the Secrets of the Mass, which before the Offertory was fixed as a part of the rite, served as the only kind of Offertory prayers. At the Third Mass of Christmas, the Secret says “By the new birth of Thy only-Begotten Son, sanctify, o Lord, the sacrifices offered (oblata); and cleanse us from the stains of our sins.” “Oblata” is the past participle of the highly irregular verb “offerre – to offer”, and refers to that which will be offered in the action of the Canon as if it were already offered. This, despite the fact that Latin has a common future passive participle which might have be chosen, to say “…sanctify the sacrifices which will be offered.” (The form in this case would be “offerenda.”)

There are many other examples which might be drawn from the Secrets of various Masses written in all periods. With them should also be included the very title of the Secret commonly found in the ancient sacramentaries, maintained by the Ambrosian Rite, and restored to general use in the Missal of Paul VI, namely, “Super oblata – the prayer over the things that have been offered,” where it might just as well have been called “Super offerenda – over the things which will be offered.” There is no warrant for imagining that the proleptic use of the past tense form “sacrificed” or any similar terms indicates a belief that the Eucharistic Sacrifice, or some other adjunct sacrifice, took place before the Canon. The presence of such language in the Offertory simply extends backwards by a few minutes a traditional way of speaking which has been almost universally a part of Christian worship from the most ancient times.

There is also, however, a broader meaning of the term “prolepsis”, which is given by the Roman rhetorician Quintilian in The Institutions of Oratory. (Book 9, chapter 2, 16-18)

Anticipation, or, as the Greeks call it, prolepsis, whereby we forestall objections, is of extraordinary value in pleading; it is frequently employed in all parts of a speech, but is especially useful in the beginning. However, it forms a genus in itself, and has several different species. (After listing some of the specific types of prolepsis) … And, most frequent of all, there is preparation, whereby we state fully why we are going to do something or have done it. Anticipation may also be employed to establish the meaning or propriety of words,…In the first article in this series, I cited an essay by Bruce D. Marshall, who points out that the theological writers of the Scholastic period paid much more attention to the question of the Real Presence than they did to that of the Sacrifice of the Mass. While “the sacrificial character of the Eucharist had never been contested in the Western church, (or the Eastern, for that matter) at the time when Bonaventure and Aquinas wrote”, the Real Presence had been “a regular subject of theological dispute in the West for several hundred years”. (Rediscovering Aquinas and the Sacraments: Studies in Sacramental Theology, p.42; edd. Matthew Levering and Michael Dauphinais; Liturgy Training Publications, 2009)

For this reason, we find that in his Book of Sentences, the principle theology textbook of the High Middle Ages, Peter Lombard devotes but a single article to the question of the Sacrifice of the Mass. (Lib. IV, dist. 12.5) Both St. Bonaventure and St. Thomas Aquinas, in their commentaries on the Sentences (the medieval equivalent of a doctoral thesis), do not comment on this article, although they refer to it in passing elsewhere. Marshall describes the situation thus: “Thomas, it seems, does not so much deliberately ignore the sacrificial side of the Eucharist as follow an established pattern that does not see this as a problem needing special attention.” (ibid.)

On the other hand, prominent heresies about the Real Presence have arisen at several points in the Church’s history. At the very beginning of the Scholastic period, Berengarius of Tours (999-1088) caused a huge controversy by attacking St Paschasius Radbertus’ teachings on the Real Presence, an attack for which he was condemned, imprisoned and forced to retract. St Norbert, who founded the Premonstratensian Order in 1119, famously combatted and extirpated the heresies of Tanchelm, which included the complete denial of the Real Presence. In the following generation, St. Bernard identified among the errors of Peter Abelard “his opinion…on the Sacrament of the altar,” summed up as the ninth on the list of the latter’s heresies. (Epistle 188.2; cf. 189.2) Less than 30 years after the death of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Dominican John of Paris, considered by his contemporaries one of the greatest theologians at the University of Paris, tentatively proposed that belief in transubstantiation was not de fide, and put forth a theory of “impanation,” looking back to some of the ideas of Berengarius’ followers. In our own times, Pope Paul VI found it necessary in the encyclical Mysterium Fidei to reassert the Council of Trent’s teaching on transubstantiation, and reject by name the new heresies of “transignification” and “transfinalization”, as well as the proposition that “Christ the Lord is no longer present in the consecrated hosts which remain once the celebration of the sacrifice of the Mass is finished.” (parag. 11)

Now although the Offertory prayers predate the Scholastics, we may fairly say that their position in the liturgy of the Mass was consolidated in the Scholastic period, the era in which the missal would displace the use of the earlier sacramentaries, lectionaries and graduals. The medieval missals have various forms of the Offertory, some simpler and some more complex, but to take the most widely used example, that of the Roman Missal refers to “sacrifice” in various ways, but never uses the term “bread.” The most commonly used Offertory prayer Suscipe sancta Trinitas is found in many medieval missals that have none of the other Roman prayers, and also makes no reference to bread.

This constant use of “sacrifice” without “bread” is a prolepsis in the broader sense given by Quintilian; it establishes the proper meaning of terms, excluding in anticipation any idea that the liturgical act of offering offers bread. This declares in advance, against the many Eucharistic heresies past and present, what the Canon does not do. It is then left it to the Canon itself, the older part of the Mass of the Faithful, to declare right before the consecration what it does do, namely, make present “for us the Body and Blood ... of the Lord Jesus Christ.”