The following article was written by Fr. Martial Caron, S.J. and originally published in the June-September 1961 edition of Kateri (Volume 13, No. 3) -- a periodical whose purpose was to promote the cause of St. Kateri Tekakwitha. Given our interest in the fascinating subject of the Roman liturgy in the Native American missions, it only seemed natural to republish it here -- and we are very grateful for the kind permission of the editor of Kateri to do so, as well as to Claudio Salvucci who first brought the article to our attention. This was to be the first part of a longer article, though sadly it would appear Fr. Caron was never able to complete his piece -- at least so far as I can tell.

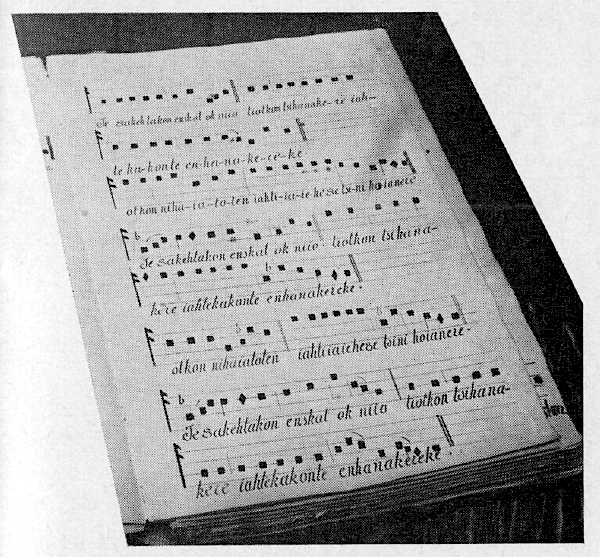

Finally, I should note that the image below did not accompany the original article, but rather appeared in another edition of Kateri.* * *Plainchant in Caughnawaga

by Fr. Martial Caron, S.J.The

Catholic Digest (December, 1960) carried an article condensed from the

Abbey Message by the Rev. Gabriel Frank, O.S.B. The title, "Gregorian Chant in English", is an eye-catcher. An eye-opener might be quite adequately applied to the contents. The facts related therein may even turn out to be Chapter One in the history of a well known and much written about problem-child: The-Vernacular-in-the-Liturgy.

Here is the fact. Each day at 4pm, the Benedictine Sisters at St. Scholastica's Convent, Fort Smith, Ark. sing Vespers; in the evening, Compline; and on major feast days they sing the Little Hours, in good plain English words adapted to plain chant. The article tells us the genesis of

The Monastic Vesperal completed and printed in 1958. We are informed that it is the first of its kind in English, but that it has counterparts in Spanish, Japanese, Chinese, Indian, and German.

The author of the article admits that "Adaptation was not easy. Even now the transcribers say that had they known the difficulties they would have never had the nerve to start." This concession will partly satisfy, or, at least, soothe somehow those who still accept the notion that Gregorian music and English words are incompatible. But, at Fort Smith, the Sisters like to tell of people, constrained almost by force to listen to Vespers in English, who were converted by one session in the Chapel. Many others who came to scoff have remained to praise.

This happens to be a long introduction to the few words about plain chant in Indian, at Caughnawaga, that I have been asked to write for

Kateri. The story at Fort Smith is short. Documents and witnesses are available. Not so at our Mission.

Singing hymns in Indian dates back to the very early missions. Most of us know of a Christmas Carol in Huron. The words were written by St. Jean de Brebeuf on a French folk song. Many other hymns have been added to the list since then. Many also are the attempts to adapt Indian words to classic and modern polyphony: motets, masses, and even cantatas --

The Seven Last Words by Theodore Dubois, to mention but one.

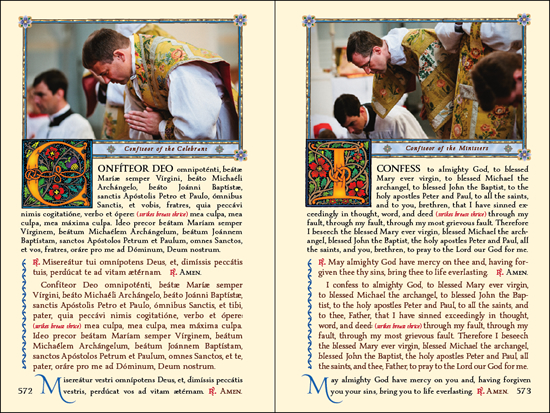

![]()

The adaptation of Indian words to plain chant is a well known fact to all our friends. They realize that the use of the Indian language in the liturgy is daily practice. On Sunday, at the High Mass, they can hear the choir singing in Indian the

Asperges me, the Proper, the Ordinary, Hymns, everything except the responses to the celebrant which are still sung in Latin.

When was the adaptation made? By whom? Where? To what extent? By what authority? These and many other questions are raised by some visitors and rightly so. In many instances, and in matters of history in particular, questions are much more readily asked than answered. In the present case, one may express an opinion. That is about all. This opinion has no professional pretensions whatever. It simply rooted from and grew with the frequent use of books and documents that happen to be the working tools of the choirmaster at Caughnawaga.

Among these books and documents stands prominently

Livre de chant en indien pour la messe et les vêpres composé par Mr Fr Marcoux missre de St Régis (1878).

The book is handwritten by the Rev. Fr. N. V. Burtin, O.M.I., then pastor at Caughnawaga, and preceded by a long preface of six pages. Here are a few samples of its contents:

The importance of singing in all religions, from Moses down to King David, through to the Catholic Church, to the Councils, to the popes, who have considered singing an important part of the liturgy and kept a watchful eye over its quality and uniformity: hence the exclusive use of Latin.

Nevertheless the Church, always a tender mother, has authorized or at least tolerated, singing in the vernacular during the services in some missions, in particular in the missions among our Indians. The Holy See has even authorized this practice by an indult to the missionaries among the Indians of the New World. It is in virtue of this indult, and by the consent of the bishops that this practice of singing in the vernacular exists especially in the three Catholic Mohawk villages of Canada.

Since many years, there were handwritten books for singing, more or less at variance, more or less faulty. Some years ago, the Rev. François Marcoux, missionary at St. Regis for forty years, had composed a book in the closest conformity with the edition of "

Chant Romain" in use in the diocese of Montreal. The present choir book is nothing more than a reprint of his work.

But Fr. Burtin tells us that: "We have added the antiphons for Vespers; some alleluias; some tracts for lent. We have revised the translation. We have inserted the notation for the entire mass of the dead with the absolution and also the notation of the hymns at the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. These were sung from memory and quite erroneously.

"We have recopied Father Marcoux's work in three large books to be used by the men and women singers; the present volume is intended for the Missionary of Sault St. Louis and his successors. Some members of the choir are making copies for their personal use and they know nearly all the present book. We are not sorry for having consecrated two or three years almost exclusively to this unpalatable labor, if it may awaken in the souls entrusted to our care, the sentiments of faith, piety, gratefulness, love and compunction which the Church endeavors to produce in the hearts of the faithful through her liturgy..."

Tekaronhianeken -- Father Burtin's Indian name -- completed his preface and his transcription of Father Marcoux's book on November 26, 1878.

-- Martial Caron, S.J.

Originally published in: Kateri (Volume 13, No. 3) June-September 1961. Reprinted with permission.![]()

![]()