The most frequently repeated criticism of the new

CDF decrees that allow priests

ad libitum use (albeit under clear conditions) of new prefaces and the feasts of saints canonized after 1960 has been that the decrees introduce or risk introducing into the celebration of the

usus antiquior an unwelcome and indeed uncharacteristic spirit of “optionitis.” Critics will say that the classical Roman rite is known and loved for its objectivity, stability, and fixity — these being the qualities of any perfected liturgical tradition — and that the clergy should not have options at their disposal.

While I agree that the classical rite has these desirable qualities, I think we should be careful not to exaggerate our case by speaking as if options do not have a longstanding place within it — a highly circumscribed place, to be sure, and one that does not threaten the integrity and “predictability” of the rite, but still, at the end of the day, options.

I will look at several examples: alternative readings; votive Masses and Masses

pro aliquibus locis; multiple orations; some minor matters; and, paraliturgically, the style of vestments.

Alternative ReadingsUnlike the new lectionary, the old lectionary, built into the missal, almost never gives an option as to what reading is to be used on any given day or for any given Mass formulary. However, there are a few instances in the Commons of “alternative readings.” For example:

- in the Mass Me exspectaverunt for Virgin Martyrs, the Gospel is Mt 13:44–52 or Mt 19:3–12;

- in the Mass In medio ecclesiae for Doctors, the Epistle is 2 Tm 4:1–8 or Ecc 39:6–14;

- in the Mass Salus autem for several martyrs, the Gospel is Lk 12:1–8 or Mt 24:3–13.

It gets really interesting with the Mass

Laetabitur justus for a martyr not a bishop, where

three epistles are listed: 2 Tim 2:8–10 and 3:10–12; Jas 1:2–12; and 1 Pet 4:13–19, as well as

two Gospels: Mt 10:26–32 and Jn 12:24–26.

There is a rubric in the Commons section of the Missal — first appearing, I think, in the 1920 edition — that states that the Epistles and Gospels printed within one of the Commons can be used

ad libitum for the Mass of a Saint, unless the Mass formulary directs otherwise. In the Sanctorale, there is either the minimal instruction to follow the Common or, more rarely, additional directions to use a specific Gospel. A rubrical expert I consulted had never seen diocesan

ordines specifying these in any way; he has a collection of about 50 which, though differing greatly in style and content, make no reference to the choice of pericopes where several are given. We should see this as a small example of liberty within the otherwise (blessedly) monolithic old missal.

In my admittedly limited experience over the past few decades, priests rarely avail themselves of these alternative readings. It seems they follow the principle articulated by a friend of mine: “Whatever text will be the least trouble to read is the one that is likely to be read.” (He initially came up with this principle to explain why, with the new lectionary, priests so rarely break out of the mold of the lectio continua that plods along from day to day, even though for almost any of the saints they could choose a more appropriate reading if they wished.) Yet hand missals always print these alternative readings right alongside the other readings for the Common, so it is hard to see why they should not be used, at least occasionally. This is a case where admirable Scripture readings already given in the old missal are being neglected.

Votive Masses and Missae pro aliquibus locisWe take it for granted that any time there is a feria, when the Mass of the preceding Sunday could be said again, a priest is also free to make a choice of any of the Votive Masses contained in the Missal. There is a longstanding custom to use the Mass of the Most Holy Trinity on Monday; that of the Holy Angels on Tuesday; that of St. Joseph, the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, or All Holy Apostles on Wednesday; that of the Holy Ghost, the Blessed Sacrament, or Jesus Christ Eternal High Priest on Thursday; that of the Holy Cross or of the Passion of Our Lord on Friday; and that of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday — but this is merely a custom and does not have any obliging force.

Beyond these popular Votive Masses are a host of others that some priests use quite regularly and others seem strangely unfamiliar with or uninterested in: Mass for the Sick (I have never actually been present when this formulary has been used!); Mass for the Propagation of the Faith (interestingly, this one has an alternative Epistle, 1 Tim 2:1–7; the Epistle listed first is Ecclus 36:1–10, 17–19); Mass Against the Heathen; Mass for the Removal of Schism; Mass in Time of War; Mass for Peace; Mass for Deliverance from Mortality or in Time of Pestilence; Mass of Thanksgiving; Mass for the Forgiveness of Sins; Mass for Pilgrims and Travellers; Mass for Any Necessity; Mass for a Happy Death. (I would add that when a priest is going to celebrate with one of these formularies, he should somehow announce it to the people, either in the bulletin if he has decided it in advance, or on a sheet posted near the inside church door, or in a brief mention after emerging from the sacristy and before starting the prayers at the foot of the altar.)

Moreover, altar missals usually feature a section towards the back called

Missae pro aliquibus locis, Masses for certain places. Like Votive Masses, these too may be chosen under certain conditions. My 1947 Benziger altar missal, with a commendatory letter signed by Cardinal Spellman, has quite a substantive “M.P.A.L.” section: page (131) to page (196). It includes such worthy feasts as The Translation of the Holy House of the Blessed Virgin Mary on December 10, the Expectation of Our Lady on December 18, the Espousal of the Blessed Virgin and St Joseph on January 23, the Flight of Our Lord Jesus Christ into Egypt on February 17, the Feast of the Prayer of Our Lord Jesus Christ on the Tuesday after Septuagesima, and many others.

All of these feasts share in common the trait that they are not normally prescribed but allowed to be used when there is no other impediment. Therefore, they must be chosen; they are, in that sense, options.

Multiple OrationsOne of the worst casualties of the 1960 rubrical revisions was the loss of multiple orations (collects, secrets, and postcommunions) at Mass and the Divine Office. This runs contrary to the Roman tradition in the second millennium, when multiple orations were a universal feature.

The history of the question of how many orations were allowed is quite complex and I intend to write more about it another time. Here it suffices to speak of the period after 1570, when it was normal for the priest to say the oration of the day, followed sometimes by a commemoration of a saint, other times by a required seasonal oration or required prayer (

oratio imperata), and concluding with a third oration at his choice (

ad libitum eligenda). There is a magnificent corpus of orations printed in the Tridentine Missal for precisely this reason, so few of which have remained in use after the draconian limitations imposed by the Roncallian rubrical reform.

We can see here, once again, that Holy Mother Church recognized a certain “ordered liberty” on the part of the celebrant, who was thus able to pray liturgically for his own needs, for those of the local community, or for those of the larger world.

Minor Matters

Five other areas in which a choice is required are:

1. Whether to precede the Sunday High Mass with the Asperges, or to start with the entrance procession accompanied by the Introit antiphon;

2. Whether to remain standing or to sit down during the Kyrie, the Gloria, and the Credo;

3. Which tone to use for the orations, readings, and Preface;

4. Whether or not to use incense at a

Missa cantata;

5. Whether to observe an “external solemnity” for Corpus Christi and/or the Sacred Heart of Jesus, to enable the maximum number of faithful to participate in the Procession for the one, and devotions for the other. It is important to recognize that here we are looking not as an obligatory transferral, where the feast is simply packed up and

moved — an aberration possible only in the Novus Ordo — but at a

separate additional celebration of some feast, which has already been celebrated on the correct day.

It is true that the foregoing choices are limited and the things being chosen are entirely defined (no room for creativity or extemporization). Nevertheless, they constitute options.

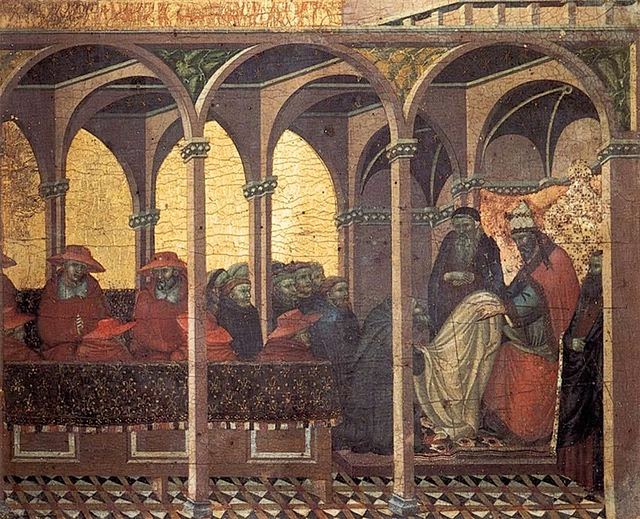

![]() |

| Gothic vestments |

![]() |

| “Roman” vestments |

Style of VestmentsWhile this final example does not concern something in the liturgical rite as such but only something associated with it, it is (oddly) one of the most controversial among traditionalists: I refer to the simple fact that the celebrant has, in theory, the option of wearing either Gothic vestments or Roman vestments. (I say “in theory” because not every sacristy is equipped with both kinds.)

As far as I know, while Eastern Christian vestments vary a great deal in quality of material and ornamentation, they do not vary as regards the fundamental design: there are not radically different “styles.” In the Western tradition, on the other hand, the original vestments received their aesthetic perfection in the so-called Gothic period, but, over the course of the Renaissance and the Counter-Reformation, a strikingly different style emerged, known (more or less accurately) as the Roman style. The difference between a Gothic conical chasuble and a Roman “fiddleback” chasuble could not be more pronounced.

Some, especially in the Liturgical Movement which first sipped the chalice of medieval romanticism before drowning in the cup of modern rationalism, insisted that the Roman style was an outrageous corruption; for others of a reactionary bent, it has become a shibboleth of Tridentine identity. One still occasionally hears enthusiasts explaining to their neighbors at the coffee hour (at least back when such things existed) that “at the Novus Ordo the priest wears this full draping kind of chasuble, but at the Latin Mass he wears the old-fashioned Roman fiddleback.” If I overhear something like that, I share with them photographs of glorious traditional Masses from Australia, where Gothic is practically the only thing in existence, whether architecturally or vesturally.

Personally I think there is room for both styles. Noble vestments have been created along the entire spectrum; aesthetic preferences are not only allowed but inevitable. Again, to my knowledge, the Church has never specified that one or another style of vestments must be used, as long as every essential piece is present (including the amice and maniple); she allows an ordered liberty of choice.

![]() |

| St Thomas Aquinas: fittingly honored on March 7, even in Lent |

Concluding ThoughtsThe decree

Cum Sanctissima permits, among other things, the observance of saints during Lent whose feasts were always impeded and reduced to commemorations by the 1960 code of rubrics’ insistence on privileging every feria of Lent. No one disputes that the Lenten ferias are absolutely wonderful, and they deserve their prominence. But it was poor thinking that allowed for no flexibility with regard to celebrating, even during Lent, feasts of saints who enjoy a particular prominence in this or that community. Surely for Catholic schools, St. Thomas Aquinas may get his full due on March 7; surely for seminaries and religious communities, St. Gregory the Great on March 12; surely for the Irish, St. Patrick on March 17. The CDF decree restores a reasonable flexibility, with the feria always commemorated. (The Novus Ordo runs into intractable difficulties because it has abandoned the wisdom of commemorations: when two things conflict, both should somehow be liturgically present, rather than one of them simply being dumped. The same problem, it must be admitted, already affects the 1962 missal to some extent —

yet another reason to return to the 1920

editio typica.)

In regard to the foregoing examples, I would say that clergy and laity are so accustomed to the choices involved that perhaps they do not even notice that a choice

is involved. What I mean is that we expect a priest to have the freedom to choose a Votive Mass on a feria, and everything else about the Mass is so predictable that it all seems inevitable, but a major choice was made beforehand to do the Votive instead of repeating the prior Sunday.

Not every choice need be construed as, or need have the psychological and pastoral effect of, the deservedly decried optionitis of the Novus Ordo. In the Tridentine rite, all options are safely folded within the dominating unity of its architecture and the exacting prescriptions of its rubrics, and therefore acquire the same rituality. In the Novus Ordo, in stark contrast, the options are so numerous, and concern such basic elements of the liturgy — its opening rite and penitential rite, the readings of the day vs. those of the Commons, whether the offertory is said aloud or silently, which Eucharistic prayer to use (!), what and when to sing, etc. etc. — that the rite itself can barely hold on to its rituality and becomes, in a sense, a giant Worship Option. This, it seems to me, is the fundamental difference between the

usus antiquior, even with the new options placed at its disposal, and the

usus recentior.

Visit Dr. Kwasniewski’s website, SoundCloud page, and YouTube channel.