For today’s feast of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary, here is the Virgin at Prayer by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato, generally known simply as Sassoferrato, who lived from 1609 to 1685.

Records of the commemoration of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary on September 8th go back to the 6th century; the Solemnity of Mary’s Immaculate Conception was later fixed to December 8, nine months prior.

Here is a bit of a commentary on the feast from Fr Matthew Mauriello: “The primary theme portrayed in the liturgical celebration of this feast day is that the world had been in the darkness of sin and with the arrival of Mary begins a glimmer of light. That light which appears at Mary’s holy birth preannounces the arrival of Christ, the Light of the World. Her birth is the beginning of a better world: ‘Origo mundi melioris.’ The antiphon for the Canticle of Zechariah at Morning Prayer expressed these sentiments in the following way: ‘Your birth, O Virgin Mother of God, proclaims joy to the whole world, for from you arose the glorious Sun of Justice, Christ our God; He freed us from the age-old curse and filled us with holiness; he destroyed death and gave us eternal life.

“The second reading of the Office of Readings is taken from one of the four sermons written by St. Andrew of Crete (660-740) on Mary’s Nativity. He too used the image of light: ‘...This radiant and manifest coming of God to men needed a joyful prelude to introduce the great gift of salvation to us...Darkness yields before the coming of light.’ ”

This painting, like the painting of St Gregory the Great by Vignali described last week, is in the baroque style of the 17th century. Again, we see the sharp contrast between light and dark, symbolizing the Light overcoming the darkness, and again like the Vignali painting, the face is in partial shadow, ensuring that this is distinct in style from a portrait (I described the reasons behind this in more detail in the earlier posting).

There is an additional element here in the portrayal of the face that was not so strongly present in Vignali’s painting. The facial features are highly idealized and bear the likeness of the ancient Greek classical ideal.

Sassoferrato’s training and influences were all in the classical baroque school. This is a stream within baroque art that looks to Raphael from 100 years before as its inspiration. Raphael’s faces, in turn, strongly reflected the classical Greek ideal. This was the model for the teaching methods of three related artists of the Caracci family in the late 16th century, (the most famous of the three being Annibale), who founded a school from which most of the influential figures in the classical baroque line emerged.

All Christian sacred art must have a balance between idealism, which points to what we might become, and naturalism, which roots the image in the particular, what we see and know in the here and now. The different styles of Christian sacred art look different from each other because they look to different sources for their ideal, and because of the exact balance of idealism and naturalism they reflect. Baroque classicism is called thus to distinguish it from “baroque naturalism”, which, although still partially idealized, has a greater emphasis on natural appearances. Ribera would be an example of the naturalistic school, and Poussin was one of the most famous proponents of baroque classicism.

We can see the similarities in the facial features of the Sassoferrato Virgin, Raphael’s Alba Madonna, (which I describe in more detail in a posting here,) and the ancient Greek statue the Venus of Arles from the Louvre. This strong idealization is another way that the artist ensures that portrayal of Our Lady does not look a portrait of the girl from next door dressed up in historical costume.

Here is the Venus of Arles:

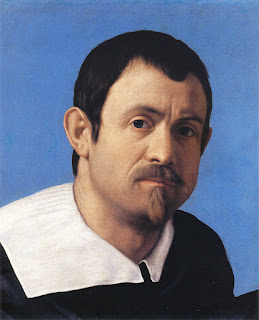

We can see the difference between the way in which sacred art and mundane art are painted by contrasting these works with Sassoferrato’s self portrait. Notice how in the portrait the image engages the viewer much more directly; we look deeply into his eyes, the deep shadow is absent, and the background is blue rather than black, so that the contrast between light and dark is not so pronounced. There is still some shadow in the face certainly - this is necessary in order to describe form - but it is not so marked. Also there is not such an obvious fusion of the natural features of the face with those of the Greek ideal as we would see in the sacred art.

Sassoferrato’s Virgin is in the National Gallery in London, and I have a great fondness for it. Even long before my conversion, it was one of those paintings that I always made a point of going to look at every time I visited the gallery; the National Gallery has no entrance fee, so I often used to just drop in for 20 minutes on my way home from work, or even sometimes just to escape the rain! The peaceful repose and expression of Our Lady, which is even more apparent if you see the original, always drew me in.

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School of the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”

Records of the commemoration of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary on September 8th go back to the 6th century; the Solemnity of Mary’s Immaculate Conception was later fixed to December 8, nine months prior.

Here is a bit of a commentary on the feast from Fr Matthew Mauriello: “The primary theme portrayed in the liturgical celebration of this feast day is that the world had been in the darkness of sin and with the arrival of Mary begins a glimmer of light. That light which appears at Mary’s holy birth preannounces the arrival of Christ, the Light of the World. Her birth is the beginning of a better world: ‘Origo mundi melioris.’ The antiphon for the Canticle of Zechariah at Morning Prayer expressed these sentiments in the following way: ‘Your birth, O Virgin Mother of God, proclaims joy to the whole world, for from you arose the glorious Sun of Justice, Christ our God; He freed us from the age-old curse and filled us with holiness; he destroyed death and gave us eternal life.

“The second reading of the Office of Readings is taken from one of the four sermons written by St. Andrew of Crete (660-740) on Mary’s Nativity. He too used the image of light: ‘...This radiant and manifest coming of God to men needed a joyful prelude to introduce the great gift of salvation to us...Darkness yields before the coming of light.’ ”

This painting, like the painting of St Gregory the Great by Vignali described last week, is in the baroque style of the 17th century. Again, we see the sharp contrast between light and dark, symbolizing the Light overcoming the darkness, and again like the Vignali painting, the face is in partial shadow, ensuring that this is distinct in style from a portrait (I described the reasons behind this in more detail in the earlier posting).

There is an additional element here in the portrayal of the face that was not so strongly present in Vignali’s painting. The facial features are highly idealized and bear the likeness of the ancient Greek classical ideal.

Sassoferrato’s training and influences were all in the classical baroque school. This is a stream within baroque art that looks to Raphael from 100 years before as its inspiration. Raphael’s faces, in turn, strongly reflected the classical Greek ideal. This was the model for the teaching methods of three related artists of the Caracci family in the late 16th century, (the most famous of the three being Annibale), who founded a school from which most of the influential figures in the classical baroque line emerged.

All Christian sacred art must have a balance between idealism, which points to what we might become, and naturalism, which roots the image in the particular, what we see and know in the here and now. The different styles of Christian sacred art look different from each other because they look to different sources for their ideal, and because of the exact balance of idealism and naturalism they reflect. Baroque classicism is called thus to distinguish it from “baroque naturalism”, which, although still partially idealized, has a greater emphasis on natural appearances. Ribera would be an example of the naturalistic school, and Poussin was one of the most famous proponents of baroque classicism.

We can see the similarities in the facial features of the Sassoferrato Virgin, Raphael’s Alba Madonna, (which I describe in more detail in a posting here,) and the ancient Greek statue the Venus of Arles from the Louvre. This strong idealization is another way that the artist ensures that portrayal of Our Lady does not look a portrait of the girl from next door dressed up in historical costume.

Here is the Venus of Arles:

We can see the difference between the way in which sacred art and mundane art are painted by contrasting these works with Sassoferrato’s self portrait. Notice how in the portrait the image engages the viewer much more directly; we look deeply into his eyes, the deep shadow is absent, and the background is blue rather than black, so that the contrast between light and dark is not so pronounced. There is still some shadow in the face certainly - this is necessary in order to describe form - but it is not so marked. Also there is not such an obvious fusion of the natural features of the face with those of the Greek ideal as we would see in the sacred art.

Sassoferrato’s Virgin is in the National Gallery in London, and I have a great fondness for it. Even long before my conversion, it was one of those paintings that I always made a point of going to look at every time I visited the gallery; the National Gallery has no entrance fee, so I often used to just drop in for 20 minutes on my way home from work, or even sometimes just to escape the rain! The peaceful repose and expression of Our Lady, which is even more apparent if you see the original, always drew me in.

— ♦—

—JAY W. RICHARDS, Editor of the Stream and Lecturer at the Business School of the Catholic University of America said about it: “In The Way of Beauty, David Clayton offers us a mini-liberal arts education. The book is a counter-offensive against a culture that so often seems to have capitulated to a ‘will to ugliness.’ He shows us the power in beauty not just where we might expect it — in the visual arts and music — but in domains as diverse as math, theology, morality, physics, astronomy, cosmology, and liturgy. But more than that, his study of beauty makes clear the connection between liturgy, culture, and evangelization, and offers a way to reinvigorate our commitment to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the twenty-first century. I am grateful for this book and hope many will take its lessons to heart.”