Even though St. Matthew does not specify in his Gospel how many Magi came from the East to worship the Christ Child, the customary representation of three of them is one of the most solidly consistent and ancient traditions of Christian art. A very small number of early images have more than three, and one painting in the catacomb of Ss. Peter and Marcellinus has only two, but these are mere anomalies. It is commonly supposed that artists settled on three Magi to correspond to their three gifts, which, in turn, have been read from very ancient times as symbols of Christ’s divinity, mortality and regality. This is undoubtedly true, but there is another, equal important reason for showing three. As far back as the pre-Socratic philosophers, the Greeks, following the Babylonians, divided the world into three parts, Asia, Africa and Europe. This division predates Christianity, but was received by Christians and Jews as part of their sacred history; each continent was believed to be populated by the descendents of one of the sons of Noah, Asians from Shem, Africans from Ham, and Europeans from Japheth. (The word ‘Semite’ derives from the name ‘Shem’, and the term ‘Hamito-semitic’, formerly used for the Afro-asiatic linguistic family, derives from Ham and Shem.)

The three Magi are therefore the symbolic representatives of the three parts of world, coming to worship the Creator and Savior. As Pope St. Leo the Great writes in his first sermon on the Epiphany (from the Breviary of St. Pius V):

In the rougher sorts of images, such as the one shown above, with the general lack of detail, the three Magi are not distinguished from one another, although their offerings are. In the Catacomb of Priscilla, however, one of the frescos shows each of the three in a different color, one from each of the three parts of the world. This image of the third-century is especially important because it is in the funeral chapel of a very wealthy family; the many paintings within it were of a very high quality, though they have deteriorated greatly over the centuries. It is safe to say, therefore, that they were conceived among the most educated Christians, and it is not surprising to find artistic ideas born in such an environment flourishing in the great churches built in early centuries after the end of the persecutions.

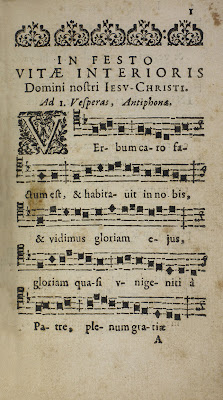

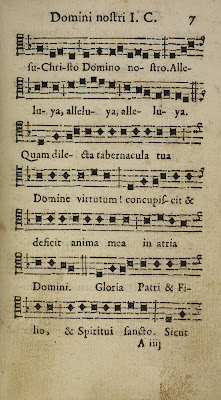

Particularly in Rome, where people from every part of the Empire lived, such an image represents the revelation of Christ as the Redeemer of all men, and the coming all peoples to salvation. This is reflected in many texts of the Roman liturgy of Epiphany, such as the following antiphons of Matins:

In the sixth century, a new element is introduced, that of the Three Ages of Man, a concept derived from Aristotle. (Rhetoric II.12) In the 6th-century mosaics of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, the Magi are represented one as a youth, one as a adult, one as an elderly man. Here, the idea of the universality of Christ’s salvation is expanded to refer not only to all nations, but all aspects of humanity. For the same reason, the Magi are leading a procession of 22 sainted virgins towards the Madonna and Child, while 26 male saints are shown coming towards an adult Christ on the opposite side of the church.

In all of these images, the Magi are shown wearing the clothes of “barbarians”, i.e., non-Romans, the Phrygian cap, and elaborately decorated garments with pants and sleeves, instead of the looser and simpler Roman togas. This tradition continues into the Carolingian period, as seen here in the lowest part this ivory panel from the British Museum.

By the last quarter of the 10th century, however, a new tradition had emerged of showing the Magi as kings, as seen in this page of the Benedictional of St. Aethelwold, made in the 970s. (Click for a larger and clearer view.)

Where the Carolingian era looked back to older artistic models of the late antique Roman tradition, the Romanesque period seems to be following more closely the words of the liturgy; in particular, the sixtieth chapter of Isaiah, and the seventy-first Psalm, both associated with the Epiphany from very early times. The first six lines of the former is the traditional Epistle of the Roman Mass, clearly chosen for the beginning words “Arise, be enlightened, O Jerusalem: for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee.”, and for the reference to two of the three gifts of the Magi at the end, “all they from Saba shall come, bringing gold and frankincense: and showing forth praise to the Lord.” The third verse of the same passage reads, “And the gentiles shall walk in thy light, and kings in the brightness of thy rising.” Psalm 71 is one of the five “Messianic psalms”, along with Psalms 2, 44, 88 and 109, traditionally regarded as important prophecies of the coming of the Messiah. All five are sung in the Office of Christmas, but 71 is also sung at Matins of the Epiphany, with the tenth verse as its antiphon, “The kings of Tharsis and the islands shall offer presents: the kings of the Arabians and of Saba shall bring gifts.” Both passages refer to gifts, the land of Saba (Sheba), and kings, and so they were naturally understood to refer to each other; hence the givers of these gifts were understood to be kings. This idea is reinforced by several other passages of Isaiah which refer to kings in a context that would naturally lead them to be associated with the Epiphany:

The three Magi are therefore the symbolic representatives of the three parts of world, coming to worship the Creator and Savior. As Pope St. Leo the Great writes in his first sermon on the Epiphany (from the Breviary of St. Pius V):

(I)t concerns the salvation of all men, that the infancy of the Mediator between God and men was already being declared to the whole world, while it was yet confined within a small village. For although He had chosen the people of Israel, and of that people, a single family, whence He might take upon Himself the nature of all mankind; nevertheless He did not want the first dawn of His rising to lie hidden within the narrow walls of His Mother’s abode; but rather, He wished to be acknowledged at once by all, He who deigned to be born for all.Despite the varying quality of early Christian images, from roughly scratched inscriptions on funerary stones to elaborate sarcophagi and frescoes, nearly all early images of the Magi show them moving towards Christ, as he sits in the lap of the enthroned Virgin; this also represents the calling of all of the nations of the earth to conversion and redemption.

| A funerary slab of the third century from the Vatican Museums' Pio |

Particularly in Rome, where people from every part of the Empire lived, such an image represents the revelation of Christ as the Redeemer of all men, and the coming all peoples to salvation. This is reflected in many texts of the Roman liturgy of Epiphany, such as the following antiphons of Matins:

from Psalm 28: Bring to the Lord, O ye children of God: adore ye the Lord in his holy court.

from Psalm 65: Let all the earth adore thee, and sing to thee: let it sing a psalm to thy name, o Lord.

from Psalm 85: All the nations thou hast made shall come, and adore before thee, O Lord.

In the sixth century, a new element is introduced, that of the Three Ages of Man, a concept derived from Aristotle. (Rhetoric II.12) In the 6th-century mosaics of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, the Magi are represented one as a youth, one as a adult, one as an elderly man. Here, the idea of the universality of Christ’s salvation is expanded to refer not only to all nations, but all aspects of humanity. For the same reason, the Magi are leading a procession of 22 sainted virgins towards the Madonna and Child, while 26 male saints are shown coming towards an adult Christ on the opposite side of the church.

In all of these images, the Magi are shown wearing the clothes of “barbarians”, i.e., non-Romans, the Phrygian cap, and elaborately decorated garments with pants and sleeves, instead of the looser and simpler Roman togas. This tradition continues into the Carolingian period, as seen here in the lowest part this ivory panel from the British Museum.

By the last quarter of the 10th century, however, a new tradition had emerged of showing the Magi as kings, as seen in this page of the Benedictional of St. Aethelwold, made in the 970s. (Click for a larger and clearer view.)

Where the Carolingian era looked back to older artistic models of the late antique Roman tradition, the Romanesque period seems to be following more closely the words of the liturgy; in particular, the sixtieth chapter of Isaiah, and the seventy-first Psalm, both associated with the Epiphany from very early times. The first six lines of the former is the traditional Epistle of the Roman Mass, clearly chosen for the beginning words “Arise, be enlightened, O Jerusalem: for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee.”, and for the reference to two of the three gifts of the Magi at the end, “all they from Saba shall come, bringing gold and frankincense: and showing forth praise to the Lord.” The third verse of the same passage reads, “And the gentiles shall walk in thy light, and kings in the brightness of thy rising.” Psalm 71 is one of the five “Messianic psalms”, along with Psalms 2, 44, 88 and 109, traditionally regarded as important prophecies of the coming of the Messiah. All five are sung in the Office of Christmas, but 71 is also sung at Matins of the Epiphany, with the tenth verse as its antiphon, “The kings of Tharsis and the islands shall offer presents: the kings of the Arabians and of Saba shall bring gifts.” Both passages refer to gifts, the land of Saba (Sheba), and kings, and so they were naturally understood to refer to each other; hence the givers of these gifts were understood to be kings. This idea is reinforced by several other passages of Isaiah which refer to kings in a context that would naturally lead them to be associated with the Epiphany:

Kings shall see, and princes shall rise up, and adore for the Lord's sake, because he is faithful, and for the Holy One of Israel, who hath chosen thee. (chapter 49, 7)The later part of the fifteenth century saw the emergence of a new motif, the placement of the Nativity scene amid the ruins of a large building, or with a ruined building in the background. On a purely technical level, this reflects the interest of Renaissance artists in Roman antiquities, as part of the general revival of Roman learning and art. Theologically, the ruins also represent the world, which Christ came to renew, as He says in the Apocalypse, “Behold, I make all things new.” The artists of the period thus associated their renewal of the intellectual and artistic achievements of the Classical world with what Christ did for the whole human race in the Incarnation.

And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and queens thy nurses: they shall worship thee with their face toward the earth. (49, 23)

The Lord hath prepared his holy arm in the sight of all the gentiles: and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God. … He shall sprinkle many nations, kings shall shut their mouth at him: for they to whom it was not told of him, have seen: and they that heard not, have beheld. (52, 10 and 15)

And the gentiles shall see thy just one, and all kings thy glorious one. (62, 2)

|

| A traditional Neapolitan Nativity scene of the 18th century, now on permanent display at the Roman church of Saints Cosmas and Damian. The ruins visible on the right side are the Column of Phocas and the Temple of Saturn, both in the Roman Forum, barely 200 meters from the ancient entrance to the church. The panoply of human activity of every kind represents the sanctification of all of human life and endeavor by the union of God and man in Christ. |