A comment on a very old post and some discussion of Dominican traditions with brothers in our Western Dominican Province House of Studies, as to vesting of the deacon, have prompted this overview of deacons and subdeacons and their vesture in the traditional Dominican Rite.

ON VESTMENTS OF THE DEACON AND SUBDEACON

1. In the traditional Dominican Rite, what are the proper vestments for a deacon and subdeacon?

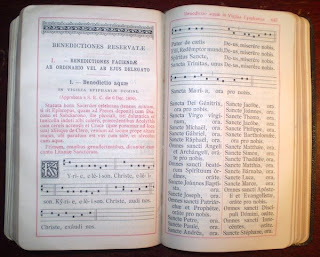

Like the priest, the deacon and subdeacon wear the amice, alb, cinture, and maniple. On certain occasions, they also wear the dalmatic. The Domi![]() nican Rite does not follow the Roman practice of distinguishing the dalmatic (worn by the deacon) from the tunicle (worn by the subdeacon), in which the dalmatic has one bar between the claves (vertical stripes) and the tunicle two. Although this distinction is sometimes seen at Dominican Masses (vestments with Roman decorations are more common), properly, there is no distinction in style or name between the deacon and subdeacon’s dalmatics. You can see, to the right, a photo of the deacon and subdeacon at the Gospel during an Easter Mass in the mid-1950s at St. Albert the Great Priory in Oakland CA. Both dalmatics are identical (although lacking the traditional claves).

nican Rite does not follow the Roman practice of distinguishing the dalmatic (worn by the deacon) from the tunicle (worn by the subdeacon), in which the dalmatic has one bar between the claves (vertical stripes) and the tunicle two. Although this distinction is sometimes seen at Dominican Masses (vestments with Roman decorations are more common), properly, there is no distinction in style or name between the deacon and subdeacon’s dalmatics. You can see, to the right, a photo of the deacon and subdeacon at the Gospel during an Easter Mass in the mid-1950s at St. Albert the Great Priory in Oakland CA. Both dalmatics are identical (although lacking the traditional claves).

2. On what days do the deacon and subdeacon wear the dalmatic at Mass?

The deacon and subdeacon wear dalmatics, according to the Caeremoniale S.O.P. (1869), n. 548-50:

a. On all Sundays

b. On all Feasts of Three Lessons and above (which after the 1960 calendar Reform means all IIId Class feasts and above).

c. For any Votive Mass when the calendar feast of that day is of IIId Class or above.

d. On weekdays of Octaves when the Mass of the day is proper to the octave (after 1960, these were only the Octaves of Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost).

e. At Requiem Masses on the day of death, burial, anniversary, or (pro causa sollemnitatis) when said for a public figure. Otherwise, if the Requiem replaces the Conventual Mass, then the dalmatic is used only if the proper Mass of the Day would have required it. Otherwise, not.

e. Before 1923, dalmatics were also worn at the Order’s special Votive Masses that replaced ferials of week. The calendar reforms of St. Pius X abolished these special Votive Masses so as to restore the celebration of ferials.

Otherwise, the deacon and subdeacon wear only the amice, alb, cinture, maniple, and (for the deacon) the stole. Priests, of course, always wear the chasuble at Mass. So, the dalmatic is not worn on: ferials not part of an octave, true vigils (i.e., NOT the anticipated Mass of a Sunday or Feastday--rather, the at the Mass of the day before the Ascension, Pentecost, St. John the Baptist, Sts. Peter and Paul, St. Lawrence, Assumption, and Christmas), and Ember Days. Nor do our deacons and subdeacons wear dalmatics or folded chasubles on Good Friday: on that day they wear only the amice, alb, cinture, maniple, and (for the deacon) the stole, even though the prior (or priest) celebrating the service wears a cope (Caermon. (1869), n. 1483).

3. At what other times is the dalmatic worn?

According to the Caeremoniale (1869), n. 551:

a. At processions when the priest wears a cope.

b. When singing the Genealogy and the Last Discourse of Jesus.

c. When assisting a priest wearing a cope at Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

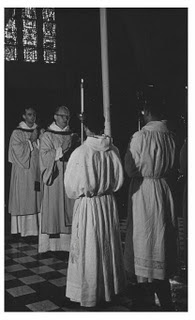

One should note that, in the Dominican Rite, the priest does NOT wear the cope for the Asperges (unless a procession of the brethren precedes: the entrance of the ministers at Mass is NOT such a procession). At the Asperges, all t![]() hree ministers do, however, wear the maniple. Note that this is different from Roman practice. I have included a photo of the Dominican major minsters at the Asperges (sorry about the quality) to illustrate our practice. It might also be added that the Dominican practice is to wear the maniple when preaching, although it was very common in the Western Province for the priest to remove the chasuble and place it on the altar before preaching. I suspect that this is because Dominicans usually pin the maniple on the sleeve of the alb and this would be hard to remove; thus the chasuble is removed instead. Current practice, however, in the Western Province is to remove neither when preaching at Dominican Rite Masses.

hree ministers do, however, wear the maniple. Note that this is different from Roman practice. I have included a photo of the Dominican major minsters at the Asperges (sorry about the quality) to illustrate our practice. It might also be added that the Dominican practice is to wear the maniple when preaching, although it was very common in the Western Province for the priest to remove the chasuble and place it on the altar before preaching. I suspect that this is because Dominicans usually pin the maniple on the sleeve of the alb and this would be hard to remove; thus the chasuble is removed instead. Current practice, however, in the Western Province is to remove neither when preaching at Dominican Rite Masses.

4. What would this mean for Dominicans who celebrate the modern Roman Rite?

Strictly speaking, nothing is required by these older norms. But the new Roman liturgical books leave a lot of leeway for the vesting of the deacon. Although the proper vestments of the deacon in the new rite include the dalmatic, it is not required (unlike the chasuble for priest celebrants). So it is possible to adopt some of the older Dominican practice.

Using the principle of progressive solemnity, it would be possible, or even preferable, for Dominican deacons to leave aside the dalmatic on ferials. This was, in fact, the practice when I was a student in the 1970s and 1980s at our House of Studies. But if, in clear violation of the rubrics, deacons do not wear an amice, alb, and cinture but only their white habit (a practice that seems to be dying out in the Western Province but is often seen elsewhere, then, by all means, they should wear the dalmatic on ferials (and all other Masses where they violate the rubrics) to make their infraction less visible to the congregation.

ON SUBDEACONS

The revival of the traditional Dominican Rite in some provinces since Summorum Pontificum, along with its long-continued and now expanding use in our Western Dominican Province, raises some new questions on the office and function of the subdeacon. I will attempt to answer these.

1. Who was able to serve as subdeacon in the Traditional Dominican Rite before Vatican II?

Obviously any friars having been ordained to the subdeacon could serve; as well as priests and deacons, who were always previously ordained subdeacons. Now, the Caeremoniale S.O.P. (1869), n. 864, is very explicit, and quotes the General Chapter of Bologna (1564), on this: “No one may wear liturgical vestments and solemnly chant the Epistle if he has not at least been promoted the rank of subdeacon.” As at a Missa Cantata, the Epistle has always been sung "by any cleric” (Bonniwell, Ceremonial, p. 141) — which today would mean any clerical brother, as the tonsure is no longer given, this legislation refers only to the Epistle at the Solemn Mass. So what was and is commonly called a “straw subdeacon” (i.e., a man, normally a cleric, who vested as a subdeacon and performed that role) is clearly forbidden. Although the Caeremoniale calls the practice an abuse, it was not uncommon in the Order before Vatican II for lay brothers to serve as "subdeacons" at Solemn Masses. In fact, an elderly cooperator (lay) brother told me that he regularly functioned as a subdeacon in the missions and in parishes when no priest was available. Since in the Pre-Vatican-II church “straw subdeacons” were tolerated in the Roman Rite, the this use seems to have been generally adopted by Dominicans.

2. Who may serve as a subdeacon today in the traditional Dominican Rite?

When the Dominican Rite Solemn Mass is celebrated today, a deacon or priest would be able to function as a subdeacon as they are both clerics (from their deacon ordination) and have been ordained to a rank above subdeacon. This is the common practice in our Western Province. What is to be done, if no priest or deacon is available, or those priests present cannot, for one reason or another, perform the duties of the subdeacon? Today the only ministries given before ordination to the deaconate are those of the lector and the acolyte (which may be called a “subdeacon,” if the bishop’s conference wishes). Neither are canonically “clerics” because the clerical state now begins with the deaconate (even if one has received tonsure in a religious institute for whom the rites are performed using the old books).

As before Vatican II, when a problem presents itself on which our books are silent, one must turn to the practice of the Roman Rite as the mother rite. For the Roman Rite, in the extraordinary form, a letter from the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei (Prot. No. 24/92, 7 June, 1993) provided that an installed acolyte (that is, an acolyte installed using the new Roman Roman Rite) may serve as subdeacon, but he is not to wear the maniple. The justification given for this decision is that, previously, one who had received the minor order of acolyte was permitted to serve, without the maniple, as in the liturgical role of subdeacon when that was needed. I myself am not sure that this restriction on using the maniple was correct, but that is another matter. This letter represents the current liturgical law.

There were, in the old days, two other restrictions on what such men serving as subdeacons could not do beyond not wearing the maniple. They could not put water in the chalice. and they could not dry the vessels. The deacon had to do those things. Ecclesia Dei omitted those restrictions. Was it an oversight? Probably not. Since a modern installed acolyte can purify the vessels (GIRM #279), he certainly can dry them. And today, when there are many extra chalices for concelebrants, they may be prepared with water and wine by the sacristan before Mass — the current practice at St. Peters in Rome (“On Multiple Calices,” Zenit.org, Oct. 9, 2007). In addition, the legal dictum “silence gives consent” leads to the conclusion that when Ecclesia Dei choose to list only one restriction on an acolyte acting as subdeacon, this implied that any other older restrictions were no longer binding. With good reason!

Can a friar who has not received either the ministries of acolyte and lector, or has only received the ministry of lector, or, for that matter, can a simple layman, function as a subdeacon at Dominican Rite Solemn Mass? I would say no, even if lay brothers did this before Vatican II. The responsum from Ecclesia Dei cited above allows, to function as subdeacon, only to those men who have, for one reason or another, been formally installed in the modern ministry of acolyte. I do not think I have to tell our readers that this does not mean installation as an Extraordinary Eucharistic Minister or being commissioned as an altar boy in a parish! I would add that the installation of lectors and acolytes in the new rite is permanent: it does not “go away” if the seminarian or friar who received it leaves the seminary or order.

Let us hope that along with the Missae Cantatae sung weekly, monthly, or annually, in our Western Dominican Parishes, that the full Solemn Mass become a more regular event.

This posting originally appeared on Dominican Liturgy.![]()

ON VESTMENTS OF THE DEACON AND SUBDEACON

1. In the traditional Dominican Rite, what are the proper vestments for a deacon and subdeacon?

Like the priest, the deacon and subdeacon wear the amice, alb, cinture, and maniple. On certain occasions, they also wear the dalmatic. The Domi

nican Rite does not follow the Roman practice of distinguishing the dalmatic (worn by the deacon) from the tunicle (worn by the subdeacon), in which the dalmatic has one bar between the claves (vertical stripes) and the tunicle two. Although this distinction is sometimes seen at Dominican Masses (vestments with Roman decorations are more common), properly, there is no distinction in style or name between the deacon and subdeacon’s dalmatics. You can see, to the right, a photo of the deacon and subdeacon at the Gospel during an Easter Mass in the mid-1950s at St. Albert the Great Priory in Oakland CA. Both dalmatics are identical (although lacking the traditional claves).

nican Rite does not follow the Roman practice of distinguishing the dalmatic (worn by the deacon) from the tunicle (worn by the subdeacon), in which the dalmatic has one bar between the claves (vertical stripes) and the tunicle two. Although this distinction is sometimes seen at Dominican Masses (vestments with Roman decorations are more common), properly, there is no distinction in style or name between the deacon and subdeacon’s dalmatics. You can see, to the right, a photo of the deacon and subdeacon at the Gospel during an Easter Mass in the mid-1950s at St. Albert the Great Priory in Oakland CA. Both dalmatics are identical (although lacking the traditional claves).2. On what days do the deacon and subdeacon wear the dalmatic at Mass?

The deacon and subdeacon wear dalmatics, according to the Caeremoniale S.O.P. (1869), n. 548-50:

a. On all Sundays

b. On all Feasts of Three Lessons and above (which after the 1960 calendar Reform means all IIId Class feasts and above).

c. For any Votive Mass when the calendar feast of that day is of IIId Class or above.

d. On weekdays of Octaves when the Mass of the day is proper to the octave (after 1960, these were only the Octaves of Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost).

e. At Requiem Masses on the day of death, burial, anniversary, or (pro causa sollemnitatis) when said for a public figure. Otherwise, if the Requiem replaces the Conventual Mass, then the dalmatic is used only if the proper Mass of the Day would have required it. Otherwise, not.

e. Before 1923, dalmatics were also worn at the Order’s special Votive Masses that replaced ferials of week. The calendar reforms of St. Pius X abolished these special Votive Masses so as to restore the celebration of ferials.

Otherwise, the deacon and subdeacon wear only the amice, alb, cinture, maniple, and (for the deacon) the stole. Priests, of course, always wear the chasuble at Mass. So, the dalmatic is not worn on: ferials not part of an octave, true vigils (i.e., NOT the anticipated Mass of a Sunday or Feastday--rather, the at the Mass of the day before the Ascension, Pentecost, St. John the Baptist, Sts. Peter and Paul, St. Lawrence, Assumption, and Christmas), and Ember Days. Nor do our deacons and subdeacons wear dalmatics or folded chasubles on Good Friday: on that day they wear only the amice, alb, cinture, maniple, and (for the deacon) the stole, even though the prior (or priest) celebrating the service wears a cope (Caermon. (1869), n. 1483).

3. At what other times is the dalmatic worn?

According to the Caeremoniale (1869), n. 551:

a. At processions when the priest wears a cope.

b. When singing the Genealogy and the Last Discourse of Jesus.

c. When assisting a priest wearing a cope at Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

One should note that, in the Dominican Rite, the priest does NOT wear the cope for the Asperges (unless a procession of the brethren precedes: the entrance of the ministers at Mass is NOT such a procession). At the Asperges, all t

4. What would this mean for Dominicans who celebrate the modern Roman Rite?

Strictly speaking, nothing is required by these older norms. But the new Roman liturgical books leave a lot of leeway for the vesting of the deacon. Although the proper vestments of the deacon in the new rite include the dalmatic, it is not required (unlike the chasuble for priest celebrants). So it is possible to adopt some of the older Dominican practice.

Using the principle of progressive solemnity, it would be possible, or even preferable, for Dominican deacons to leave aside the dalmatic on ferials. This was, in fact, the practice when I was a student in the 1970s and 1980s at our House of Studies. But if, in clear violation of the rubrics, deacons do not wear an amice, alb, and cinture but only their white habit (a practice that seems to be dying out in the Western Province but is often seen elsewhere, then, by all means, they should wear the dalmatic on ferials (and all other Masses where they violate the rubrics) to make their infraction less visible to the congregation.

ON SUBDEACONS

The revival of the traditional Dominican Rite in some provinces since Summorum Pontificum, along with its long-continued and now expanding use in our Western Dominican Province, raises some new questions on the office and function of the subdeacon. I will attempt to answer these.

1. Who was able to serve as subdeacon in the Traditional Dominican Rite before Vatican II?

Obviously any friars having been ordained to the subdeacon could serve; as well as priests and deacons, who were always previously ordained subdeacons. Now, the Caeremoniale S.O.P. (1869), n. 864, is very explicit, and quotes the General Chapter of Bologna (1564), on this: “No one may wear liturgical vestments and solemnly chant the Epistle if he has not at least been promoted the rank of subdeacon.” As at a Missa Cantata, the Epistle has always been sung "by any cleric” (Bonniwell, Ceremonial, p. 141) — which today would mean any clerical brother, as the tonsure is no longer given, this legislation refers only to the Epistle at the Solemn Mass. So what was and is commonly called a “straw subdeacon” (i.e., a man, normally a cleric, who vested as a subdeacon and performed that role) is clearly forbidden. Although the Caeremoniale calls the practice an abuse, it was not uncommon in the Order before Vatican II for lay brothers to serve as "subdeacons" at Solemn Masses. In fact, an elderly cooperator (lay) brother told me that he regularly functioned as a subdeacon in the missions and in parishes when no priest was available. Since in the Pre-Vatican-II church “straw subdeacons” were tolerated in the Roman Rite, the this use seems to have been generally adopted by Dominicans.

2. Who may serve as a subdeacon today in the traditional Dominican Rite?

When the Dominican Rite Solemn Mass is celebrated today, a deacon or priest would be able to function as a subdeacon as they are both clerics (from their deacon ordination) and have been ordained to a rank above subdeacon. This is the common practice in our Western Province. What is to be done, if no priest or deacon is available, or those priests present cannot, for one reason or another, perform the duties of the subdeacon? Today the only ministries given before ordination to the deaconate are those of the lector and the acolyte (which may be called a “subdeacon,” if the bishop’s conference wishes). Neither are canonically “clerics” because the clerical state now begins with the deaconate (even if one has received tonsure in a religious institute for whom the rites are performed using the old books).

As before Vatican II, when a problem presents itself on which our books are silent, one must turn to the practice of the Roman Rite as the mother rite. For the Roman Rite, in the extraordinary form, a letter from the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei (Prot. No. 24/92, 7 June, 1993) provided that an installed acolyte (that is, an acolyte installed using the new Roman Roman Rite) may serve as subdeacon, but he is not to wear the maniple. The justification given for this decision is that, previously, one who had received the minor order of acolyte was permitted to serve, without the maniple, as in the liturgical role of subdeacon when that was needed. I myself am not sure that this restriction on using the maniple was correct, but that is another matter. This letter represents the current liturgical law.

There were, in the old days, two other restrictions on what such men serving as subdeacons could not do beyond not wearing the maniple. They could not put water in the chalice. and they could not dry the vessels. The deacon had to do those things. Ecclesia Dei omitted those restrictions. Was it an oversight? Probably not. Since a modern installed acolyte can purify the vessels (GIRM #279), he certainly can dry them. And today, when there are many extra chalices for concelebrants, they may be prepared with water and wine by the sacristan before Mass — the current practice at St. Peters in Rome (“On Multiple Calices,” Zenit.org, Oct. 9, 2007). In addition, the legal dictum “silence gives consent” leads to the conclusion that when Ecclesia Dei choose to list only one restriction on an acolyte acting as subdeacon, this implied that any other older restrictions were no longer binding. With good reason!

Can a friar who has not received either the ministries of acolyte and lector, or has only received the ministry of lector, or, for that matter, can a simple layman, function as a subdeacon at Dominican Rite Solemn Mass? I would say no, even if lay brothers did this before Vatican II. The responsum from Ecclesia Dei cited above allows, to function as subdeacon, only to those men who have, for one reason or another, been formally installed in the modern ministry of acolyte. I do not think I have to tell our readers that this does not mean installation as an Extraordinary Eucharistic Minister or being commissioned as an altar boy in a parish! I would add that the installation of lectors and acolytes in the new rite is permanent: it does not “go away” if the seminarian or friar who received it leaves the seminary or order.

Let us hope that along with the Missae Cantatae sung weekly, monthly, or annually, in our Western Dominican Parishes, that the full Solemn Mass become a more regular event.

This posting originally appeared on Dominican Liturgy.

During 2011, Corpus Christi Watershed's

During 2011, Corpus Christi Watershed's  It might be helpful to first explain what the Roman Gradual is, as priests are sometimes hesitant or embarrassed to admit ignorance regarding this book. The Roman Gradual is a collection of prayers (chants) carefully assigned to each Mass. Each Proper is usually about one or two sentences long and almost always an excerpt from Sacred Scripture. These prayers (chants) have been developed and perfected by the Western Church for more than 1,500 years. Believe it or not, musical notation itself was invented for the sole purpose of notating these chants. Furthermore, thanks to technological advances, we can view the earliest manuscripts of the Roman Gradual without leaving the comfort of our home. Here are but a few examples that will leave lovers of Gregorian chant utterly bewildered with delight:

It might be helpful to first explain what the Roman Gradual is, as priests are sometimes hesitant or embarrassed to admit ignorance regarding this book. The Roman Gradual is a collection of prayers (chants) carefully assigned to each Mass. Each Proper is usually about one or two sentences long and almost always an excerpt from Sacred Scripture. These prayers (chants) have been developed and perfected by the Western Church for more than 1,500 years. Believe it or not, musical notation itself was invented for the sole purpose of notating these chants. Furthermore, thanks to technological advances, we can view the earliest manuscripts of the Roman Gradual without leaving the comfort of our home. Here are but a few examples that will leave lovers of Gregorian chant utterly bewildered with delight:  The prayers (chants) found in the Roman Gradual are called by many names: Graduale Propers, Sung Propers, Mass Propers, etc. Having been refined by the Church over so many centuries, the Propers contain deep theology and perfectly suite each Mass, whether it is Christmas Day, Holy Thursday, Pentecost, Epiphany, etc. The Consilium (the group of bishops and experts set up by Pope Paul VI to implement the Constitution on the Liturgy)

The prayers (chants) found in the Roman Gradual are called by many names: Graduale Propers, Sung Propers, Mass Propers, etc. Having been refined by the Church over so many centuries, the Propers contain deep theology and perfectly suite each Mass, whether it is Christmas Day, Holy Thursday, Pentecost, Epiphany, etc. The Consilium (the group of bishops and experts set up by Pope Paul VI to implement the Constitution on the Liturgy)  In the post-Conciliar liturgy, we no longer have true Missals, because they would be 4,000 pages long. The post-Conciliar liturgy added all kinds of things: a three-year cycle of readings, a two-year cycle of readings, numerous options, and much more, to say nothing of the possibility of different languages that can now be used in the Mass.

In the post-Conciliar liturgy, we no longer have true Missals, because they would be 4,000 pages long. The post-Conciliar liturgy added all kinds of things: a three-year cycle of readings, a two-year cycle of readings, numerous options, and much more, to say nothing of the possibility of different languages that can now be used in the Mass. However, if what I have said above is true, why does the Roman Missal in the Ordinary Form contain the Entrance and Communion antiphons? And why are they so often different texts than what is indicated in the Roman Gradual? The clearest answer comes to us in a

However, if what I have said above is true, why does the Roman Missal in the Ordinary Form contain the Entrance and Communion antiphons? And why are they so often different texts than what is indicated in the Roman Gradual? The clearest answer comes to us in a  As we know, the GIRM allows for a choice in the singing of the chant after the First Reading. One can sing the Responsorial Psalm, or one can sing the Gradual chant (please do not be confused that there is a chant called the "Gradual" contained in the Roman Gradual). Paul VI noted (in the 1969 statement already quoted) that the Responsorial psalm was a very good option in Masses without singing. But what about the Alleluia and Offertory? Why were those Propers not also revised for spoken Masses, like the Entrance chant (a.k.a. "Introit") and Communion antiphons? We can only speculate, and the following are some possibilities. The Alleluia can be omitted if not sung (according to the GIRM), because in a spoken Mass, it does not make sense for the priest to "recite" the Alleluia while he processes to read the Gospel. Similarly, the Offertory Antiphon is to be omitted if not sung (according to the GIRM) because the Offertory is sung while the priest is receiving the gifts, and he cannot also read an Offertory antiphon while doing this action. Furthermore, as any student of the liturgy knows, many of the Offertory prayers were deleted in the post-Conciliar liturgy (this being one of the major differences between the Ordinary and Extraordinary form), and so perhaps we should not be altogether surprised that the Offertory antiphon did not survive.

As we know, the GIRM allows for a choice in the singing of the chant after the First Reading. One can sing the Responsorial Psalm, or one can sing the Gradual chant (please do not be confused that there is a chant called the "Gradual" contained in the Roman Gradual). Paul VI noted (in the 1969 statement already quoted) that the Responsorial psalm was a very good option in Masses without singing. But what about the Alleluia and Offertory? Why were those Propers not also revised for spoken Masses, like the Entrance chant (a.k.a. "Introit") and Communion antiphons? We can only speculate, and the following are some possibilities. The Alleluia can be omitted if not sung (according to the GIRM), because in a spoken Mass, it does not make sense for the priest to "recite" the Alleluia while he processes to read the Gospel. Similarly, the Offertory Antiphon is to be omitted if not sung (according to the GIRM) because the Offertory is sung while the priest is receiving the gifts, and he cannot also read an Offertory antiphon while doing this action. Furthermore, as any student of the liturgy knows, many of the Offertory prayers were deleted in the post-Conciliar liturgy (this being one of the major differences between the Ordinary and Extraordinary form), and so perhaps we should not be altogether surprised that the Offertory antiphon did not survive. If one examines the various versions and translations of the GIRM provided above, one notices a very curious fact. Starting in 2003, the United States made a special American adaptation allowing the "spoken" antiphons found in the Missal (for Introit and Communion) to be sung. Until this time, singing the Missal antiphons would have been considered "4th option," that is, possible, but requiring the Bishop's permission. This is at variance with the "Universal" GIRM, and neither the

If one examines the various versions and translations of the GIRM provided above, one notices a very curious fact. Starting in 2003, the United States made a special American adaptation allowing the "spoken" antiphons found in the Missal (for Introit and Communion) to be sung. Until this time, singing the Missal antiphons would have been considered "4th option," that is, possible, but requiring the Bishop's permission. This is at variance with the "Universal" GIRM, and neither the  The good news: there are many new conferences and resources promoting renewal of the sacred liturgy. Let us take the opportunity of the new Mass translation to start singing the Propers, as the Church desires.

The good news: there are many new conferences and resources promoting renewal of the sacred liturgy. Let us take the opportunity of the new Mass translation to start singing the Propers, as the Church desires.

.jpg)