This article is a continuation and conclusion of a three part series on the high altar of Tongerlo Abbey by Frater Anselm Gribbin, O.Praem. See: Part 1, Part 2.

* * *

Guest article by Frater Anselm J. Gribbin, O.Praem.

3. A Permanent Altar

In 1930 the ‘World Exhibition’ took place at Antwerp, and among the items on display in the ‘Pavilion of Catholic Life’ was a beautiful marble altar. Abbot Lamy decided to buy this for the abbey church, and by 1936 it was installed. It is made of Italian Carte D’Or marble, and consists of a plain altar-table resting on round pillars and a central support, decorated with vine branches and with grapes, a ‘Chio Rho’ symbol and, at the front (from the choir), the words, ‘Sancte Norberte ora pro nobis’.

It was a fine addition to the church, but, when it was bought, it lacked a ciborium. Therefore a new ciborium was designed by Jules Ghobert (d. 1971), who had originally designed the ambos which were already in place in the abbey church of Tongerlo.

The ciborium was a magnificent structure, built on four pillars, crowned with pinnacles and an eight sided crown of copper, with a diameter of 2,40 m.

The upper interior of the ciborium was decorated by mosaics, of four angels, which included the heraldic shields of the Order of Prémontré, Abbot Lamy, the abbey of Tongerlo, and of the Congo mission – a good many canons had worked as missionaries in the Belgian Congo, until as recently as 2012.

Carvings of ‘angel heads’ were also added to the pillars.

The work was completed by 24 December 1935. In the abbey magazine of 1936, it was related that

Another feature added to the altar was a large ‘sanctus’ candlestick (1936), made of light-green ‘Ringborg’ marble, for use during the celebration of Holy Mass. This is still in use today, though only for the paschal candle during Easter. In 1948 the altar was consecrated by Cardinal Van Roey, archbishop of Mechelen (Malines) and the primate of Belgium, and, among the relics enclosed in the altar, was one of St. Norbert. This new altar was to become the centre of the canons’ liturgical life, from the daily ‘Missa Summa’, for professions, ordinations and abbatial blessings.

Further features added to the church included new, oak choir stalls – with room for 82 – and a simpler stall for the abbot, erected in the church in 1958. This was largely the work of Br. Evermodus Van Overveld (d. 1994) and Br. Paulinus Fijneman (d. 1965), under the guidance of Lode Van den Brande, a woodcarver from Mechelen.

A new statue of Our Lady, by Francis Rooms, was given to the abbey in 1958 and placed on the south wall.

4. Further reconstruction and restoration (1990’s)

After the Second Vatican Council, the changes made to the liturgy that were affecting the Church at large also profoundly affected our Order and abbey community. Religious life also experienced profound change. Much that was of perennial value was needlessly abandoned in the rush to ‘update’ according to the ‘spirit of the council’ which may, or may not, have reflected what the council actually said. As far as the high altar was concerned, ‘architectural’ change did not take place immediately. Perhaps this was due to the fact that Mass could easily be celebrated ‘versus populum’, which was, as Pope Benedict XVI pointed out in The Spirit of the Liturgy, mistakingly viewed as ‘the characteristic fruit of Vatican II’s liturgical renewal’. Whereas, beforehand, a cross and six candles stood on the altar, the cross was now removed to the side and smaller candlesticks were used. By the 1990’s the abbey church was badly in need of a thorough restoration. For five years the interior and exterior was restored. However this very practical and necessary restoration, completed in 1999, took into account two other factors. Permission was obtained to remove the beautiful ciborium – the ambos had to remain in place - in order to reveal more clearly the neo-gothic architectural style of the church and to more easily facilitate ‘the participation of the faithful in the liturgical services’ (abbey magazine, 1999). The choir and the area around the altar was also restored to the original floor-level, partly for the same reasons. The altar was re-consecrated, this time by the (previous) abbot, which is a privilege of the Order, and a new cross was hung directly above the altar. Eventually candlesticks were placed either side of the altar.

5. Conclusion

The present abbey church, and the high altar of Tongerlo has undergone significant changes in its history. Practical considerations, such as the need for more space - in what was the largest community of religious in the Low Countries – played an important role in the development of the high altar and the interior architectural layout of the church. However we can also see, more importantly, that Tongerlo strove to implement, for most of the twentieth century, the ideals of the ‘old liturgical movement’ with a profound love for the Blessed Sacrament and the liturgical life, which is central to the canonical life. The ‘old liturgical movement’, in which Tongerlo played its part, was important in bringing about a greater awareness of the nature and substance of the liturgy to priests and people, among other things. However this movement, and its liturgical aftermath following the Second Vatican Council, was certainly not flawless. Indeed we could, in hindsight, legitimately question the wisdom of a number of the liturgical and architectural alterations we have seen in these articles, albeit well-intentioned. The same could, of course, also be said for a good many monastic churches, cathedrals and parish churches throughout the world. And yet, considering the present ‘renaissance’ or ‘rediscovery’ of the spirit and theology of the liturgy and of the rich liturgical patrimony of the Latin Church, which is beginning to make inroads in the present pontificate – and also in our Flemish abbey Deo gratias - it is unlikely that we have seen the end of the story of Tongerlo’s high altar and the rediscovery of the liturgy. The future of the ‘new liturgical movement’ lies with God, who asks us to co-operate with his divine grace, in charity.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Guest article by Frater Anselm J. Gribbin, O.Praem.

3. A Permanent Altar

In 1930 the ‘World Exhibition’ took place at Antwerp, and among the items on display in the ‘Pavilion of Catholic Life’ was a beautiful marble altar. Abbot Lamy decided to buy this for the abbey church, and by 1936 it was installed. It is made of Italian Carte D’Or marble, and consists of a plain altar-table resting on round pillars and a central support, decorated with vine branches and with grapes, a ‘Chio Rho’ symbol and, at the front (from the choir), the words, ‘Sancte Norberte ora pro nobis’.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

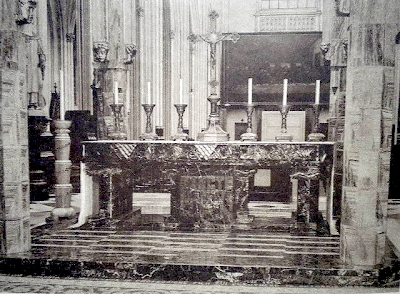

The high altar, as it appeared from 1935 to 1958. Note the ‘sanctus candle’ at the Gospel side, and the ‘angels’ heads’ on the pillars of the ciborium. The famous replica of ‘The Last Supper’ of Da Vinci can be see in the background.

Clik here to view.

The high altar, as it appeared from 1935 to 1958. Note the ‘sanctus candle’ at the Gospel side, and the ‘angels’ heads’ on the pillars of the ciborium. The famous replica of ‘The Last Supper’ of Da Vinci can be see in the background.

It was a fine addition to the church, but, when it was bought, it lacked a ciborium. Therefore a new ciborium was designed by Jules Ghobert (d. 1971), who had originally designed the ambos which were already in place in the abbey church of Tongerlo.

The ciborium was a magnificent structure, built on four pillars, crowned with pinnacles and an eight sided crown of copper, with a diameter of 2,40 m.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The altar and ciborium, from the nave and the choir before 1958.

Clik here to view.

The altar and ciborium, from the nave and the choir before 1958.

The upper interior of the ciborium was decorated by mosaics, of four angels, which included the heraldic shields of the Order of Prémontré, Abbot Lamy, the abbey of Tongerlo, and of the Congo mission – a good many canons had worked as missionaries in the Belgian Congo, until as recently as 2012.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of Abbot Lamy. These mosaics may now be found in the vestiarium.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of Abbot Lamy. These mosaics may now be found in the vestiarium.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of the Congo mission.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of the Congo mission.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of Tongerlo Abbey.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of Tongerlo Abbey.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of the Order of Prémontré.

Clik here to view.

Angel mosaic from the ciborium, with the shield of the Order of Prémontré.

Carvings of ‘angel heads’ were also added to the pillars.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

An ‘angel head’ from the ciborium. These may now be found in the vestiarium.

Clik here to view.

An ‘angel head’ from the ciborium. These may now be found in the vestiarium.

The work was completed by 24 December 1935. In the abbey magazine of 1936, it was related that

...the sons of St. Norbert have through the centuries given honour to the Blessed Sacrament, by building beautiful churches and the erection of magnificent altars. By the erection of this altar (in Tongerlo) the abbot of Tongerlo again gives testimony that for them (the Premonstratensians), nothing can be beautiful enough for the worship of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament.

Another feature added to the altar was a large ‘sanctus’ candlestick (1936), made of light-green ‘Ringborg’ marble, for use during the celebration of Holy Mass. This is still in use today, though only for the paschal candle during Easter. In 1948 the altar was consecrated by Cardinal Van Roey, archbishop of Mechelen (Malines) and the primate of Belgium, and, among the relics enclosed in the altar, was one of St. Norbert. This new altar was to become the centre of the canons’ liturgical life, from the daily ‘Missa Summa’, for professions, ordinations and abbatial blessings.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Scene from a Pontifical Mass between 1954 and 1958.

Clik here to view.

Scene from a Pontifical Mass between 1954 and 1958.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

The abbatial blessing of Abbot Joost Boel, 30 June 1953. Note also the new cross and candlesticks, made from copper.

Clik here to view.

The abbatial blessing of Abbot Joost Boel, 30 June 1953. Note also the new cross and candlesticks, made from copper.

Further features added to the church included new, oak choir stalls – with room for 82 – and a simpler stall for the abbot, erected in the church in 1958. This was largely the work of Br. Evermodus Van Overveld (d. 1994) and Br. Paulinus Fijneman (d. 1965), under the guidance of Lode Van den Brande, a woodcarver from Mechelen.

A new statue of Our Lady, by Francis Rooms, was given to the abbey in 1958 and placed on the south wall.

4. Further reconstruction and restoration (1990’s)

After the Second Vatican Council, the changes made to the liturgy that were affecting the Church at large also profoundly affected our Order and abbey community. Religious life also experienced profound change. Much that was of perennial value was needlessly abandoned in the rush to ‘update’ according to the ‘spirit of the council’ which may, or may not, have reflected what the council actually said. As far as the high altar was concerned, ‘architectural’ change did not take place immediately. Perhaps this was due to the fact that Mass could easily be celebrated ‘versus populum’, which was, as Pope Benedict XVI pointed out in The Spirit of the Liturgy, mistakingly viewed as ‘the characteristic fruit of Vatican II’s liturgical renewal’. Whereas, beforehand, a cross and six candles stood on the altar, the cross was now removed to the side and smaller candlesticks were used. By the 1990’s the abbey church was badly in need of a thorough restoration. For five years the interior and exterior was restored. However this very practical and necessary restoration, completed in 1999, took into account two other factors. Permission was obtained to remove the beautiful ciborium – the ambos had to remain in place - in order to reveal more clearly the neo-gothic architectural style of the church and to more easily facilitate ‘the participation of the faithful in the liturgical services’ (abbey magazine, 1999). The choir and the area around the altar was also restored to the original floor-level, partly for the same reasons. The altar was re-consecrated, this time by the (previous) abbot, which is a privilege of the Order, and a new cross was hung directly above the altar. Eventually candlesticks were placed either side of the altar.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

View of the altar during the solemn profession of Frater Anselm, 2012.

Clik here to view.

View of the altar during the solemn profession of Frater Anselm, 2012.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

The High Altar today

Clik here to view.

The High Altar today

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

The high altar, taken from the choir, 2012.

Clik here to view.

The high altar, taken from the choir, 2012.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

View of the altar from the choir stalls, 2007.

Clik here to view.

View of the altar from the choir stalls, 2007.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

New crucifix above the high altar, by Egino Weinert from Cologne.

Clik here to view.

New crucifix above the high altar, by Egino Weinert from Cologne.

5. Conclusion

The present abbey church, and the high altar of Tongerlo has undergone significant changes in its history. Practical considerations, such as the need for more space - in what was the largest community of religious in the Low Countries – played an important role in the development of the high altar and the interior architectural layout of the church. However we can also see, more importantly, that Tongerlo strove to implement, for most of the twentieth century, the ideals of the ‘old liturgical movement’ with a profound love for the Blessed Sacrament and the liturgical life, which is central to the canonical life. The ‘old liturgical movement’, in which Tongerlo played its part, was important in bringing about a greater awareness of the nature and substance of the liturgy to priests and people, among other things. However this movement, and its liturgical aftermath following the Second Vatican Council, was certainly not flawless. Indeed we could, in hindsight, legitimately question the wisdom of a number of the liturgical and architectural alterations we have seen in these articles, albeit well-intentioned. The same could, of course, also be said for a good many monastic churches, cathedrals and parish churches throughout the world. And yet, considering the present ‘renaissance’ or ‘rediscovery’ of the spirit and theology of the liturgy and of the rich liturgical patrimony of the Latin Church, which is beginning to make inroads in the present pontificate – and also in our Flemish abbey Deo gratias - it is unlikely that we have seen the end of the story of Tongerlo’s high altar and the rediscovery of the liturgy. The future of the ‘new liturgical movement’ lies with God, who asks us to co-operate with his divine grace, in charity.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.