Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Few of our readers will require an introduction to the work of Fr. Anthony Symondson, the noted English Jesuit and architectural historian, but few besides him have done more than to return to deserved glory the name of the the Gothicist Sir Ninian Comper (1864-1960). In his latest work, he has done the same for Stephen Dykes Bower (1903-1994), a rival of Comper--and in many ways his spiritual successor. The book is yet another example of the growing reappraisal of twentieth century traditional art and architecture, particularly as Dykes Bower, being considerably younger and much longer-lived than many of the traditionalists he emulated, had not the shield of respectable old age to cover him in many of the controversies he faced during his long career. That Dykes Bower practiced well into the 1990s, and that his monumental work on St. Edmundsbury Cathedral was completed by architect Warwick Pethers only in 2007 represents a beacon of hope to those of us struggling to promote traditional building and design in a hostile age. Pethers' work is in the great tradition of Dykes Bower--it departs in the letter from Dykes Bower's own proposals (which were themselves continually evolving) but retains both the craftsmanship, dexterity and spirit of the master's work. He is, at least chronologically, the missing link between Comper's time and ours.

For us to understand him as a mere extension of Comper or a generic fin-de-siècle Goth, is, however, a mistake, and Fr. Symondson does much to show both the continuity and invention that permeates Dykes Bower's work. Dykes Bower's work appears quintessentially English, but he was not content to be narrowly national or surrender to the false romanticism of keeping ruins safely ruined. His work has a crispness, brightness and freshness that could never be called antiquarian. His taste and sources often have a cosmopolitan range, from a Spanish-Mudéjar-inspired altar frontal he designed for Durham at the start of his career to a Cosmati pavement he proposed for Westminster Abbey and which very nearly got him fired from his job as Surveyor. His restorations were simultaneously boldly imaginative--cheerful, medieval colors, bright gilding, delicate stencilwork--and, once in place, it is hard to imagine they were ever not there.

Fr. Symondson's work focuses primarily on Dykes Bower's restorations, which, he notes, was where the architect felt most at home. We find there much of the hiding-in-plain-sight character that epitomizes his genius, and nowhere is that more apparent than in Dykes Bower's work at St. Paul's Cathedral. It may startle some of our readers to discover that the splendid baldachino at St. Paul's is a replacement for a rather cluttered Victorian reredos damaged by German bombing in 1940. After the war, the controversial design was removed and in 1948, Dykes Bower's design was selected from a slate of 5 architects by the Royal Fine Art Commission. It, and Dykes Bower's war memorial chapel in the apse behind the high altar, are so perfectly attuned to the interior that it is easy to mistake them for period work; yet, while they are as fine in detail and sensibility as their surroundings, they are by no means stale exercises in archaeology, and perhaps even more imaginative than what Wren himself might have proposed.

Fr. Symondson also covers Dykes Bower's restoration of St. Vedast's in London, another Wren work which had sustained bomb damage during the Blitz--another similarly inventive and similarly appropriate work, with a novel note injected into the composition by the use of silver lead rather than gilt on the ceiling, an interesting choice that adds a certain delicacy to the already luminous white-walled interior. Dykes Bower's long tenure as Surveyor to the Fabric of Westminster Abbey, and his many small refinements to the interior, is also discussed, as are a number of his smaller restorations. Some, like his proposals for nave altars at St. Elvan's in Glamorgan and St. Paul's in Charleston, Cornwall, ought to be textbook examples on how to sympathetically render what is often an unwelcome and objectionable intrusion into the fabric of many an older church. Such a renovation has greater necessity and legitimacy in the context of the deep chancel arrangement common in English parish churches than in the shallow sanctuaries of most American Catholic churches. Still, if it must be done, Dykes Bower shows us how.

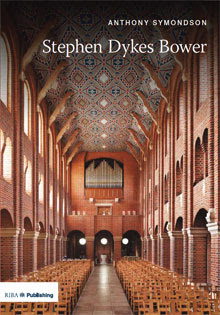

Dykes Bower's new construction and other major rebuilds should not, and are not, minimized. His 1955 church of St. John, Newbury, is a robustly-massed exercise in Luytensian-tinged brick Romanesque, its interior crowned with a stunning geometrically-stencilled wood ceiling. Symondson notes that the exterior combines "classical abstraction with Gothic construction," and the whole composition represents in a nutshell what new traditional design ought to be--literate, organically linked to the past, and quietly literate. It is probably my favorite of the work covered in the book. Like so many of Dykes Bower's other little leaps of faith, it is impossible to imagine it looking like anything else. Of his several other major additions and new buildings, space forbids me from discussing them at greater length, though it is significant to note that his one attempt to design a new secular construction caused such an uproar the model was stolen by Cambridge architecture students. In retrospect, we can say that Dykes Bower was making the right people angry.

I have no knowledge of what Dykes Bower thought of the classical revival of the 1970s and the 1980s, though his working career (which included projects not completed until 1992, within two years of his death) overlaps with that of those hardy souls who took the first great step out of the irony of postmodernism. He, a sign of contradiction to the world around him, is, as I said above, also a sign of hope to those of us now practicing in his field, showing just how narrow the chasm is between our work and the work of our ancestors, and giving the lie to all who would deny an organic continuity in the material culture of Christendom.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Clik here to view.

Few of our readers will require an introduction to the work of Fr. Anthony Symondson, the noted English Jesuit and architectural historian, but few besides him have done more than to return to deserved glory the name of the the Gothicist Sir Ninian Comper (1864-1960). In his latest work, he has done the same for Stephen Dykes Bower (1903-1994), a rival of Comper--and in many ways his spiritual successor. The book is yet another example of the growing reappraisal of twentieth century traditional art and architecture, particularly as Dykes Bower, being considerably younger and much longer-lived than many of the traditionalists he emulated, had not the shield of respectable old age to cover him in many of the controversies he faced during his long career. That Dykes Bower practiced well into the 1990s, and that his monumental work on St. Edmundsbury Cathedral was completed by architect Warwick Pethers only in 2007 represents a beacon of hope to those of us struggling to promote traditional building and design in a hostile age. Pethers' work is in the great tradition of Dykes Bower--it departs in the letter from Dykes Bower's own proposals (which were themselves continually evolving) but retains both the craftsmanship, dexterity and spirit of the master's work. He is, at least chronologically, the missing link between Comper's time and ours.

For us to understand him as a mere extension of Comper or a generic fin-de-siècle Goth, is, however, a mistake, and Fr. Symondson does much to show both the continuity and invention that permeates Dykes Bower's work. Dykes Bower's work appears quintessentially English, but he was not content to be narrowly national or surrender to the false romanticism of keeping ruins safely ruined. His work has a crispness, brightness and freshness that could never be called antiquarian. His taste and sources often have a cosmopolitan range, from a Spanish-Mudéjar-inspired altar frontal he designed for Durham at the start of his career to a Cosmati pavement he proposed for Westminster Abbey and which very nearly got him fired from his job as Surveyor. His restorations were simultaneously boldly imaginative--cheerful, medieval colors, bright gilding, delicate stencilwork--and, once in place, it is hard to imagine they were ever not there.

Fr. Symondson's work focuses primarily on Dykes Bower's restorations, which, he notes, was where the architect felt most at home. We find there much of the hiding-in-plain-sight character that epitomizes his genius, and nowhere is that more apparent than in Dykes Bower's work at St. Paul's Cathedral. It may startle some of our readers to discover that the splendid baldachino at St. Paul's is a replacement for a rather cluttered Victorian reredos damaged by German bombing in 1940. After the war, the controversial design was removed and in 1948, Dykes Bower's design was selected from a slate of 5 architects by the Royal Fine Art Commission. It, and Dykes Bower's war memorial chapel in the apse behind the high altar, are so perfectly attuned to the interior that it is easy to mistake them for period work; yet, while they are as fine in detail and sensibility as their surroundings, they are by no means stale exercises in archaeology, and perhaps even more imaginative than what Wren himself might have proposed.

Fr. Symondson also covers Dykes Bower's restoration of St. Vedast's in London, another Wren work which had sustained bomb damage during the Blitz--another similarly inventive and similarly appropriate work, with a novel note injected into the composition by the use of silver lead rather than gilt on the ceiling, an interesting choice that adds a certain delicacy to the already luminous white-walled interior. Dykes Bower's long tenure as Surveyor to the Fabric of Westminster Abbey, and his many small refinements to the interior, is also discussed, as are a number of his smaller restorations. Some, like his proposals for nave altars at St. Elvan's in Glamorgan and St. Paul's in Charleston, Cornwall, ought to be textbook examples on how to sympathetically render what is often an unwelcome and objectionable intrusion into the fabric of many an older church. Such a renovation has greater necessity and legitimacy in the context of the deep chancel arrangement common in English parish churches than in the shallow sanctuaries of most American Catholic churches. Still, if it must be done, Dykes Bower shows us how.

Dykes Bower's new construction and other major rebuilds should not, and are not, minimized. His 1955 church of St. John, Newbury, is a robustly-massed exercise in Luytensian-tinged brick Romanesque, its interior crowned with a stunning geometrically-stencilled wood ceiling. Symondson notes that the exterior combines "classical abstraction with Gothic construction," and the whole composition represents in a nutshell what new traditional design ought to be--literate, organically linked to the past, and quietly literate. It is probably my favorite of the work covered in the book. Like so many of Dykes Bower's other little leaps of faith, it is impossible to imagine it looking like anything else. Of his several other major additions and new buildings, space forbids me from discussing them at greater length, though it is significant to note that his one attempt to design a new secular construction caused such an uproar the model was stolen by Cambridge architecture students. In retrospect, we can say that Dykes Bower was making the right people angry.

I have no knowledge of what Dykes Bower thought of the classical revival of the 1970s and the 1980s, though his working career (which included projects not completed until 1992, within two years of his death) overlaps with that of those hardy souls who took the first great step out of the irony of postmodernism. He, a sign of contradiction to the world around him, is, as I said above, also a sign of hope to those of us now practicing in his field, showing just how narrow the chasm is between our work and the work of our ancestors, and giving the lie to all who would deny an organic continuity in the material culture of Christendom.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.