|

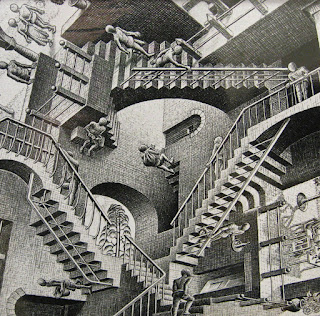

| M.C. Escher, Relativity, 1953 |

Students of visual art learn early on that a vanishing point is needed to draw three-dimensional figures accurately with proper perspective. It's one of those counter-intuitive things that turns out to be completely necessary and true in the end. Christianity, whether in historical fact, theological understanding, or social application, also requires a “vanishing point” to offer proper perspective and context. That vanishing point quite literally is Jesus Christ. All things are “through him, with him, in him.” When this focus is lost, the other pieces lose their proper perspective and relation.

What about architecture and liturgy? A centrally-located tabernacle is just the starting point for properly oriented liturgical practice. Church buildings flattened, inside out, backwards, sideways, upside down, etc, actually obscure the purpose we were all gathered in the first place. Jesus should be the visual focal point, not a sideline extra. In this sense, traditional architectural and liturgical forms are more sacred and cultivate a more transcendent experience for the faithful. Even with traditional architectural and liturgical forms, however, it all falls completely flat if Jesus Christ is not truly present... in body, blood, soul, and divinity. Keep the proper focus, and all the other pieces will fall into place. Of course, you’ll have to work hard for those other pieces, too! Visually, what is most central in your parish? Does that correspond with the ultimate reality?

What about artistic practice? Sacred art and sacred music ought to develop organically from our tradition, because it is in fact our own tradition that connects us historically with Jesus Christ. It’s not about respecting our elders or forebears. Without a real, continuous “apostolic” connection to the historical Jesus Christ, we run the risk of forgetting the Incarnation. It is the Incarnation that gives us "power to become children of God" (John 1). We are, therefore, not free to push aside the apostolic nature of our faith, which is handed down to us through our tradition, because our faith is rooted in the Incarnation, in real historical fact. Do our art and music make this connection and promote a hermeneutic of continuity?

What about parish life and community? If we ourselves are the only reason we assemble, people will self-select their peers, and our community will quickly lack the diversity and universality that makes our faith "catholic." If our values are the only reason we assemble, diversity for its own sake becomes relativism, universality for its own sake becomes universalism, and society (or community) for its own sake becomes secular. The end result of relativism is that nobody can find the truth, and the end result of universalism is that nobody gets redemption. If service to others is the only reason we assemble, our charity can become shallow or even toxic: often it is we ourselves who need to change and grow, not the people we think need our help. (Entire books have been written on the topic of so-called “toxic charity.”) But “without works, faith is dead.” If the pastor's unique message is the reason we assemble... well, quite simply we become a cult. Don't drink the Kool-aid! If the reason we assemble is Jesus Christ, however, we will have faithfulness, diversity, universality, conversion, companionship, and service to others. And by this, I mean not the "values" of Jesus Christ, the "spirit" of Christian service, the "wisdom" of the Gospel, etc; these abstractions all fall away into lesser philosophies bound up in lesser personalities. I mean, rather, Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity, as defined in the Nicene Creed.

What about the moral life and questions of personal faith and inspiration? Without Jesus Christ as a model, a companion, and a goal, why would anyone be so stupid or crazy to attempt the Christian religion, let alone make any heroic sacrifices or efforts? Why undergo the Cross if there is no Resurrection? Without a transcendent “vanishing point,” the concrete tasks at hand are simply impossible... or our goals are too low. Even the saints, our beloved Catholic darlings, are reminders in each age, each one pointing toward that transcendent "vanishing point" and reminding us that this whole Christian endeavor is indeed possible with God's help. They are not nice "fairy godmothers" we choose to remember because we like them. No, they are proven advocates in heaven, victors who have demonstrably achieved their reward, the beatific vision, who are praying that we achieve ours. There are no unintentional saints, no saints who did not know the source of their strength and virtue. Today, in their prayers and efforts on our behalf, there is no saint who does not point us back to his or her first love, Jesus Christ, the "author and finisher our faith" upon whom our faith depends from start to finish (Hebrews 12:2, Rev. 5:11-13). Jesus Christ is always and forever the center of true Christian worship and practice. Without this perspective, the whole Catholic enterprise is impossible and falls apart (Colossians 1:12-20).

Lastly, I should pause and also mention a new trend in pastoral theology, the so-called “quest for transcendence.” Admittedly we all look for transcendent truth and goodness in our lives as an answer to the grittiness of life, and these are not bad reasons to go to church. Christianity, however, is not the only religion on the market offering “transcendence.” Transcendence loosely understood is actually a very dangerous thing, because the abyss of the universe and the depths of our belly buttons do not necessarily liberate us from error, indifference, or even despair, no matter how hard we squint and struggle. As Frederick Nietzsche famously wrote, “If you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” Or as the speaker wrote in Ecclesiastes, “Vanity of vanity, all is vanity and a striving after the wind.” In other words, and by God’s design, not all answers come through our own minds – after all, we need answers bigger than that, and if the answers were intuitive we’d already know them! This is why there is revelation through Holy Scripture, through Jesus Christ himself, and through our Catholic tradition. Specifically, hope comes through the paradox of Jesus Christ, who by his Cross and Resurrection has set us free. As G.K. Chesterton wrote in Orthodoxy, Christ is a “signpost for free travelers.” So “transcendence” loosely understood is not the correct goal, but rather the redemption and grace offered us through Jesus Christ, which makes us transcendent as we become victorious “sons and daughters” of God. In other words, Catholic Christianity offers transcendence as a by-product of a much deeper process, the only one which makes that transcendence really possible. Jesus Christ is at the center of this process, and is the source of its power and effectiveness.

Do you see a theme here? Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity, is the cornerstone for all real growth and development in the spiritual life. He is the focus and measure for liturgy, community, artistic expression, sacred music, social justice, and the whole endeavor. As Christians, having Christ at the center should not be a surprise.

In the end, this is the reason we favor tradition, and the reason a faithful, obedient, reverent liturgy is so important. It’s not stuffy intellectualism, snobbery toward popular culture, love of old things, ethnocentrism, or a tendency toward familiarity; it is, rather, the perspective we must take up in order to see Jesus himself and properly fulfill our obligation to our neighbor. We must once again turn toward the Lord, who, in the Eucharist, is the "source and summit" of our life. And it’s so simple. “Remain in me, and I in you, and you will bear much fruit” (John 15:4).

In the end, this is the reason we favor tradition, and the reason a faithful, obedient, reverent liturgy is so important. It’s not stuffy intellectualism, snobbery toward popular culture, love of old things, ethnocentrism, or a tendency toward familiarity; it is, rather, the perspective we must take up in order to see Jesus himself and properly fulfill our obligation to our neighbor. We must once again turn toward the Lord, who, in the Eucharist, is the "source and summit" of our life. And it’s so simple. “Remain in me, and I in you, and you will bear much fruit” (John 15:4).