This past Sunday, the Holy Father declared two new Doctors of the Church, the German Benedictine nun St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) and St. John of Avila, (1500-1569), a Spanish secular priest and renowned preacher. By this decree, the company of the Doctors is increased to 35, and the number of women among them to four; Saints Catherine of Siena and Theresa of Avila (a supporter of John of Avila in the reform of the Spanish Church) were made the first female Doctors in 1970, and St. Therese of Lisieux was given the title by Bl. John Paul II in 1997, a few days before the centenary of her death.

![]() |

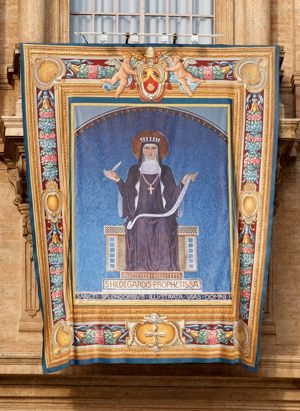

| A banner with an image of St. Hildegard, here called a prophetess, suspended from the façade of St. Peter’s for the ceremony in which she was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church. |

It is often stated that the first four Doctors of the Church, Saints Ambrose, Jerome, Augustine, and Gregory the Great, were proclaimed as such by Pope Boniface VIII in 1298. It is more accurate to say that the Pope formalized a long-established custom by ordering that their feasts be celebrated throughout the Latin Church with the same liturgical rank as the feasts of the Apostles and Evangelists. Already in the 8th century, the Venerable Bede cites the four of them as “most outstanding” among the Fathers of the Church, and the “most worthy” sources for his commentary on the Gospel of St. Luke, an assessment shared by many other writers in the following centuries. In art they are often associated with the four Evangelists; the medieval fondness for numerical symbolism in theology also tended to designate each one of them as the principal expounder of one of the four senses of the Sacred Scriptures. (See the introduction to the first volume of Henri Card. De Lubac’s

Medieval Exegesis, pp. 4-7.)

In the liturgical tradition of the Roman Rite, the four Doctors are also associated with the four Evangelists in the collections of homilies read at Matins, in which each appears as the principal (but by no means sole) commentator on one of the four Gospels. Broadly speaking, St. Jerome’s

Commentary on Matthew, St. Ambrose’s

Exposition of the Gospel according to Luke, and St. Augustine’s

Treatises on the Gospel of John are commonly read in all uses of the Divine Office. St. Mark rarely appears in the traditional Mass-lectionary of the Roman Rite, but does provide the Gospel on the greatest feast of the year, Easter, and on the Ascension; on both of these feasts, the homily at Matins in most uses is taken from St. Gregory. Therefore, the first sense in which a Father might be called a Doctor was the frequent use of his writings in the Church’s public worship.

![]() |

| St. Mark the Evangelist, with his traditional symbol, a winged lion, on the left, and St. Gregory the Great on the right, and a book of his sermons. From the ceiling of the church of Sant’Agostino in Cremona, Italy, by Bonfazio Bembo, 1452. |

Of course, many other Fathers are frequently read in the Office; outside the Use of Rome, St. Bede is foremost among them in the medieval breviaries. As he himself notes in the prologue to the commentary mentioned above, he often borrows from the earlier Doctors; his gathering of the best passages from earlier writers makes his commentaries ideal for use in prayer services. So much of Bede’s writing is taken almost word for word from other works that the medieval copyists of liturgical manuscripts often confused his writings with his sources, and accidentally added passages from the latter back into his texts.

Also prominent in the public prayer of the Church are the writings of Saints Leo the Great, Hilary of Poitier (especially in France), and Maximus of Turin. Bede, Leo and Hilary have all subsequently been made Doctors themselves; St. Maximus, on the other hand, has been the object of almost no liturgical devotion, although he is noted in the Martyrology as a man “most celebrated for his learning and sanctity.” Indeed, his writings often appear in the breviaries under the name of some other saint, usually Augustine. In the 13th century, many of the writings of St. John Chrysostom were translated into Latin, and began to find their way into the Office; in the Roman Breviary of 1529, sermons by him are read on three of the four Sundays of Lent.

![]() |

| The Four Doctors of the Church, by Pier Francesco Sacchi, ca. 1516. Note that each is accompanied by a symbol of one of the four Evangelists. |

The terms of Pope Boniface’s decree were carried over into the liturgical books of the Tridentine reform, which also added five other Doctors. Four of these were early Fathers of the Eastern church: Ss. Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and Gregory of Nazianzen. (The third Cappadocian Father, Basil’s brother Gregory of Nyssa, has never been venerated liturgically by the Latin Church.) All of them appear in various pre-Tridentine liturgical books, but the feasts of Basil and Gregory are extremely rare. In the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church was greatly concerned to assert that its teachings were those held “always, everywhere and by all”, and not medieval corruptions introduced by the “Romish Church”; the pairing of four Eastern Doctors with the traditional four Western Doctors therefore asserts the universality of the teachings held by Rome and defended by the Council of Trent. Three of them also have special connections to Rome and the Papacy. During the second of his five exiles, St. Athanasius was a guest of Pope St. Julius I, who defended him against the Arian heretics; relics of Ss. John Chrysostom and Gregory of Nazianzen were saved from the iconoclasts in the 8th century and brought to Rome, later to be placed in St. Peter’s Basilica.

![]() |

| The Chair of St. Peter in the Vatican Basilica, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1655-61. The Doctors standing further from the chair and wearing mitres are Saints Ambrose and Augustine, those closer but without mitres are Saints Athanasius and John Chrysostom. |

To this group the Dominican Pope St. Pius V added a new Doctor, his confrere St. Thomas Aquinas. Like many great theologians of the medieval period, Thomas was frequently referred to as a Doctor both in liturgical contexts and elsewhere; thus we find the calendar of a 1477 Dominican Missal noting his feast day, “Thomas, Confessor and Doctor, of the Order of Preachers.” A famous story is told that during the process of his canonization, the devil’s advocate objected that he had worked no miracles, to which a cardinal replied “Tot miracula quot articula – there are as many miracles as there are articles (in the two Summas).” During the Council of Trent, his

Summa Theologica was placed on the altar of the church alongside the Bible and the Decretals (the medieval canon law code, a copy of which was also burnt by Luther, along with his bull of excommunication.) Thus did the Council assert that its teachings, and those of the medieval tradition of both law and theology, were indeed in harmony with the teachings of Christ in the Gospel.

In 1588, Pope Sixtus V, a Franciscan and former vicar apostolic of his order, declared his confrere St. Bonaventure, the contemporary of St. Thomas, the tenth Doctor of the Church. Although another Franciscan, Duns Scotus, generally known as the “Subtle Doctor”, was far more influential at Trent, he had not been canonized; this emphasizes the fact that a Doctor of the Church in the formal sense must be recognized not only for his learning, but also for the sanctity of his life. Bonaventure had been canonized in 1472 by an earlier Franciscan Pope, Sixtus IV, (more famously the builder of the Sistine Chapel), in whose honor Sixtus V had chosen his papal name. (Duns Scotus was declared a Blessed in 1993.)

![]() |

| St. Bonaventure shows the Saints to Dante, from Canto 12 of the Paradise of the Divine Comedy. The majority of figures pointed out to Dante in this passage are famous theologians: St. Augustine, Hugh of St. Victor, Peter Comestor, Chrysostom, Anselm, and Rabanus Maurus. (Manuscript illumination by Giovanni di Paolo, 1450) |

In 1720, Pope Clement XI added a new Doctor of the Church, St. Anselm of Canterbury. This may seem a strange choice, given the many more prominent Fathers of the Church such as Leo and Bede who had not yet received the title. The Catholic Encyclopedia points out that Anselm’s contribution to Scholastic theology is like the foundation of a building: hidden but necessary, and present to every part. It seems however that at the time, the creation of the first new Doctor in 140 years was not seen as a matter of such great importance; it is not even mentioned in the official collection of Pope Clement’s acts, spanning a reign of over 20 years.

St. Anselm was quickly followed by two other new Doctors; St. Isidore of Seville, the great encyclopedist of the Middle Ages, was given the title in 1722 by Innocent XIII, and St. Peter Chrysologus by Benedict XIII in 1729. After a break of 35 years, Benedict XIV, one of the Church’s greatest scholars of hagiography, bestowed the title on St. Leo the Great, to whom more than any other of the Latin Fathers the honor was long overdue.

There then followed a pause of more than 70 years, until St. Peter Damian was given the title in 1828 by Pope Leo XII; subsequently, almost every Pope has declared at least one Doctor. (The exceptions are Gregory XVI, St. Pius X and the short-lived John Paul I.) Blessed Pius IX actually made three, including the first “modern”, St. Alphonse Liguori (1696-1787), but the record is four each by Leo XIII and Pius XI. The former’s Doctors are all of the Patristic era (including another long overdue honor, to St. Bede), while the latter recognized the fruits of the Counter-Reformation in two Jesuits, Ss. Robert Bellarmine and Peter Canisius, balanced with a Dominican, St. Albert the Great, the teacher of St. Thomas.

![]() |

| Dante meets Ss. Thomas Aquinas and Albert the Great in Canto 10 of the Paradise, among the lovers of divine wisdom. Beneath them are Boethius, St. Denis the Areopagite, Gratian, Peter Lombard, Paul Orosius, Solomon, St. Isidore of Seville, the Venerable Bede, Richard of St. Victor

and Siger of Brabant. (Giovanni di Paolo, 1450. Note that Siger, the last figure on the right, who was regarded by many as a heretic, has been partly scratched out.) |

Like Hildegard of Bingen, Albert was declared both a Saint and a Doctor of the Church at the time. The parallels between these two Germans are striking. Both were extremely learned in many different fields of study, and famous in their own lifetimes, so much so that Albert was often called “the Universal Doctor”, and Hildegard “the Sibyl of the Rhine”. For both, a formal process of canonization was begun repeatedly but never completed (7 times between them); and both were rather unexpectedly canonized equivalently by papal granting of the title “Doctor” and the extension of their feasts to the General Calendar. (See the Catholic Encyclopedia

article on “Beatification and canonization”, for an explanation of ‘equivalent canonization’.)

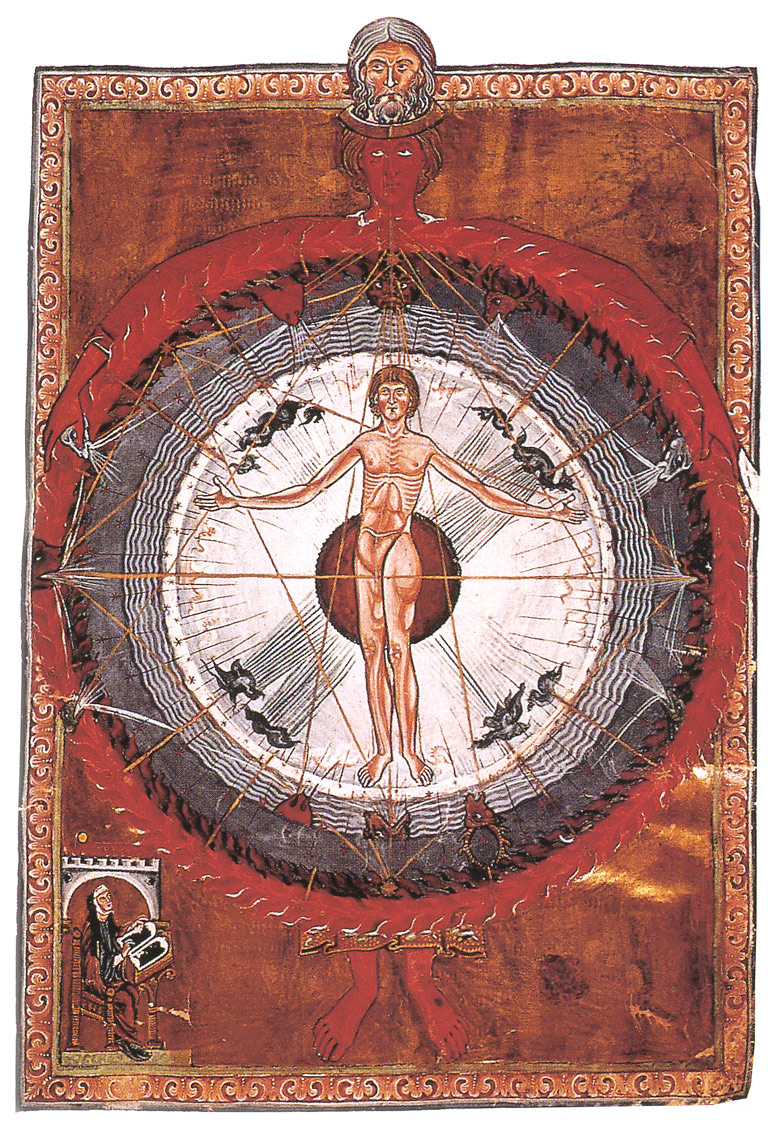

![]() |

| A famous vision of the Cosmic Man from the Book of the Divine Works by St. Hildegard of Bingen. (Biblioteca Statale, Lucca, Italy, 13th century) |

The traditional Office of a Doctor is that of a Confessor Bishop or a simple Confessor, with a few proper features; namely, the readings of Matins, the responsory

In medio Ecclesiae, (borrowed from the Office of St. John the Evangelist), and the antiphon of the Magnificat at both Vespers,

O Doctor optime. The Missal of St. Pius V contains a single Mass for Doctors, also called

In medio Ecclesiae from its

introit; but several of their feasts have their own propers or borrow them from other Masses. Many saints have been informally recognized as Doctors within a particular place or religious order by the use of these texts on their feast days;

In medio was sung as by the Cistercians as the introit of St. Bernard long before he was formally declared a Doctor in 1830, and several parts of the same Mass are used by the Dominicans on the feasts of St. Dominic and the great canon lawyer St. Raymund of Penyafort.

One notable point of difference between the pre- and post-conciliar liturgies is the absence in the former of any reference to the title of Doctor being given to women. If at some point in the future provision is made in the Extraordinary Form for the new class of Virgin Doctors, it would be sensible to use texts from traditional sources, such as the many medieval antiphons that refer to the “wise virgins” in St. Matthew 25. Another excellent source would be the proper Carmelite Office of St. Theresa of Avila, who was also spoken of informally as a Doctor by her own order long before the title was made official by the Pope. (E.g., all the chapters of her Office come from the same epistle that is read on the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas.) At the Magnificat of First Vespers, the Carmelites sing “I sought to take her to Me as my spouse, for she is the teacher (doctrix) of God’s discipline, and the chooser of His works.”, and at Second Vespers, “The nations will tell of her wisdom, and the Church will proclaim her praise.”

.png)