The Rogations traditionally held on April 25th are known as the “Greater Rogations” or “Major Litanies”, even though they were instituted later than the Minor Litanies, and are held on only one day, as opposed to three. This is because they are specifically Roman in origin, established by Pope St Gregory the Great in 590, at the very beginning of his papacy, while the Lesser Rogations were instituted in Gaul in the mid-6th century, but came to Rome only in the Carolingian period. In the Roman Rite, they consist of the Litany of the Saints, which is sung during the Procession, and a Mass, which is the same as that said on the Minor Litanies.

Even though the Ambrosian liturgy adopted this tradition from Rome, its liturgical texts for these days are rather more developed. Each of the four Rogation days has its own version of the Litany of the Saints; each of the three days of the Lesser Rogations has its own Mass, but on April 25th, the votive Mass “for penance” is said. I shall here give the liturgical texts for the Greater Rogations, along with the rubrics for their public celebration, from an edition published by the Archdiocese of Milan in 1733.

After the celebration of the Mass of St Mark, the clergy and people gather at the cathedral, and proceed from there to the basilica of St Nabor, which by the 18th century was in the care of the Franciscans, and rededicated to their Patron Saint. The archbishop, in violet stands before the altar, and begins the rite with “Dominus vobiscum”, after which the archdeacon intones the following antiphon, which is continued by the choir.

Domine Deus virtutum, Deus Is-

rael, qui eduxisti populum tuum

de terra Aegypti, et fecisti tibi

nomen gloriae, peccavimus, im-

pie egimus, iniquitatem fecimus;

miserere nobis, Salvator mundi. | O Lord God of hosts, God of Isra-

el, who led Thy people out of the

land of Egypt, and made for Thy-

self a glorious name; we have

sinned, we have done wickedly;

we have wrought iniquity; have

mercy on us, o Savior of the

world. |

The procession then makes its way to the basilica of St Victor, accompanied by the following processional antiphons. These are sung in alternation by the college of lectors, and the “maceconici”, as they were called, an Italian/Milanese corruption of “magister canonicus - the masters of the schools”. These were a group of cantors assigned to the two chapters of the cathedral specifically to maintain a high level of liturgical chant. (

Our dear departed friend Mons. Angelo Amodeo came into the chapter of the Duomo as a “maceconico.”) The second of these is the same text that forms the Introit of Ash Wednesday in the Roman Rite.

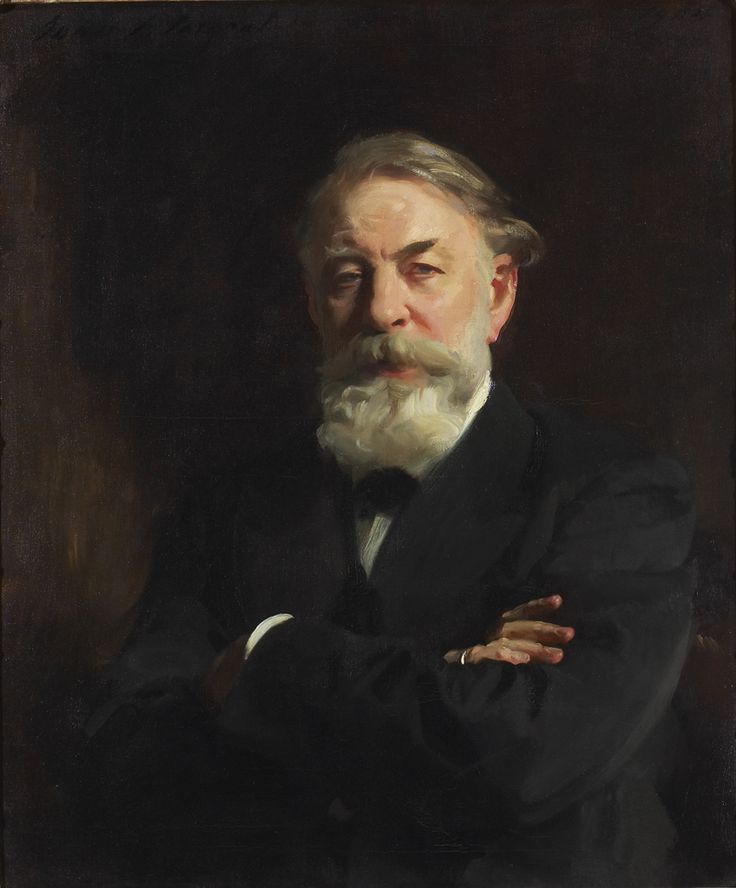

![]() |

| An Ambrosian maceconico |

Peccavimus ante te, Deus, ne

des nos in opprobrium, propter

nomen tuum, quia tu es Domi-

nus, Deus noster, quem propiti-

um exspectamus. | We have sinned before Thee, o God,

give us not unto reproach, for Thy

name’s sake, for Thou are the Lord,

our God, whom we await to show us

mercy. |

Misereris omnium Domine, et

nihil odisti eorum quae fecisti,

dissimulans peccata hominum

propter paenitentiam, et parcens

illis: quia tu es Dóminus, Deus

noster. | Thou hast mercy on all, O Lord, and

hate none of the things which Thou

hast made, overlooking the sins of

men for the sake of repentance, and

sparing them: because Thou art the

Lord our God. |

Qui fecisti magnalia in Aegyp-

to, mirabilia in terra Cham, ter-

ribilia in Mari Rubro, non tra-

das nos in manus gentium, nec

dominentur nobis, qui oderunt

nos. | Thou who didst great things in Egypt,

wondrous deeds in the land of Cham,

terrible things at the Red Sea, deliver

us not into the hands of the nations,

nor let them rule over us that hate us. |

Circumdederunt nos mala, quo-

rum non est numerus; da nobis

auxilium de tribulatione; opera

manuum tuarum ne despicias,

Domine. | Evils have surrounded us, that have

no number; grant us help in our tribu-

lation; despise not the works of Thy

hands, o Lord. |

Si fecissemus praecepta tua, Do-

mine, habitassemus cum securi-

tate et pace omni tempore vitae

nostrae; nunc quoniam peccavi-

mus, supervenerunt in nos om-

nes tribulationes; pius es, Domi-

ne, miserere nobis, et dona re-

medium populo tuo, Deus Israel. | If we had followed Thy precepts, o

Lord, we would have dwelt in secur-

ity and peace all the time of our life;

now, because we have sinned, every

tribulation has come upon us; holy art

Thou, o Lord, have mercy on us, and

give remedy, to Thy people, o God

of Israel. |

Iniquitates nostras agnoscimus,

Domine; petimus deprecantes te,

remitte nobis, Domine, peccata

nostra. | We recognize our iniquities, o Lord,

we ask Thee beseechingly; forgive us

our sins, o Lord. |

Vide, Domine, afflictionem po-

puli tui, quoniam amara est ni-

mis; humiliati enim sumus pro

peccatis nostris; exaudi nos,

qui es in caelis, quoniam non

est alius praeter te, Domine. | See the affliction of Thy people, o

Lord, for it is exceedingly bitter, for

we are laid low for our sins; hear us,

Who art in heaven, for there is no

other beside Thee, o Lord. |

Liberator noster de gentibus ira-

cundis, ab insurgentibus in nos

libera nos, Domine. | Our deliverer from the wrathful

nations, from them that rise up

against us, deliver us, o Lord. |

At the church of St Victor, the maceconici sing “Kyrie eleison” three times in a lower voice; this is repeated by the “vecchioni - old men (or) elders”, a group of laymen who participated in a formal way in many services in the Ambrosian liturgy. The readers with the head of their college then sang “Kyrie eleison” three times in a higher voice, which is also repeated by the vecchioni.

The cantors begin the litany of the Saints, which in the Ambrosian Rite is introduced by three repetitions of “Domine, miserere

– Lord, have mercy”, three of “Christe, libera nos - Christ, deliver us”, and three of “Salvator, libera nos

– o Savior, deliver us.” The names of the Saints are then sung by the cantors, to which all others answer, repeating the names and adding “intercede pro nobis.” (“Sancta Maria.

– Sancta Maria, intercede pro nobis.”) In the Roman Rite, the list of the Saints is always the same, although local Saints may be added by immemorial custom; in the Ambrosian Rite, the Saints named in the litany change from one occasion to another. On this day, after the Virgin Mary, the three Archangels are named, followed by the Apostles Peter, Paul, Andrew, and Mark, whose feast day it is; the martyrs Stephen, Felix, Fortunatus and Victor; then Pope Urban I, Tiburtius, Valerian and Cecilia. (The martyrdom of Cecilia, her betrothed Tiburtius, and his brother Valerian took place in the days of Pope Urban, 222-230; the brothers’ feast is on April 14.) There follows a group of bishops, including St Gregory, who instituted the Greater Rogations, St Satyrus, the brother of St Ambrose, then Galdinus, Charles Borromeo, and Ambrose, who always conclude the litanies in the Ambrosian Rite. The litany ends with three repetitions of “Exaudi, Christe.

R. Voces nostras. Exaudi, Deus.

R. Et miserere nobis.”, (Hear, o Christ, our voices. Hear o God, and have mercy on us.), and three

Kyrie eleisons.

The archbishop then sings the following Collect. “Omnipotens sempiterne Deus, cui sine fine potestas est miserendi, preces humilitatis nostrae placatus intende: ut quod delictorum nostrorum catena constringit, a tua nobis misericordia relaxetur. Per.

– Almighty and everlasting God, that hast power without end to show mercy, be appeased and harken to the prayers of our low estate: so that what the chain of our sins bindeth may be loosed for us by Thy mercy.”

The deacon hebdomadary, the canon assigned to serve as deacon at the capitular services that week, then intones a responsory. (The Ambrosian Rite very frequently assigns specific chants to specfic persons or groups within the chapter.)

R. Te deprecamur, Domine,

* qui es misericors et pius, esto nobis propitius.

V. Domine, exaudi orationem nostram, et clamor noster ad te perveniat.

Qui es...

– R. We beseech Thee, o Lord,

* who art merciful and holy, be merciful unto us.

V. O Lord, hear our prayer, and let our cry come unto Thee.

Who art...

The procession then goes from the altar of St Victor to that of St Gregory, as the lector and maceconici sing another group of penitential antiphons. The first of these has the same text as the famous antiphon for the

Nunc dimittis in the Dominican Office

which always moved St Thomas to tears.

Media vita in morte sumus;

quem quærimus adjutórem, nisi

te, Domine? qui pro peccatis

nostris juste irásceris. Sancte

Deus, Sancte fortis, Sancte

misericors Salvator, amarae

morti ne tradas nos. | In the midst of life, we are in death;

whom shall we seek to help us, if not

Thee, o Lord, who art justly wroth for

our sins. Holy God, holy mighty one,

holy immortal one, hand us not over

to bitter death. |

Domine, inclina aurem tuam et

audi; respice de caelo, et vide

gemitum nostrum, et de manu

mortis libera nos. | O Lord, incline Thy ear, and hear;

look down from heaven, and see

our groaning, and deliver us from

the hand of death. |

Exsurge, libera, Deus, de manu

mortis, et ne infernus rapiat

nos, ut leo, animas nostras. | Arise, deliver our souls, God, from

the hand of death, lest hell take us,

like a lion. |

Cor nostrum conturbatum est,

Domine, et formido mortis céci-

dit super nos; ad tuam pietatem

concurrimus: ne perdas pecca-

tores, misericors. | Our heart is troubled, o Lord, and the

fear of death hath fallen upon us;

we run to Thy mercy, destroy not the

sinners, merciful one. |

Domine Deus, miserere, quia anni

nostri in gemitibus consumati

sunt, et mors furibunda succedit;

Domine, libera nos. | Lord God, have mercy, for our years

are consumed in groaning, and furi-

ous death cometh after; o Lord, de-

liver us. |

At the altar of St Gregory, twelve Kyries are sung as above, followed by a second Litany of the Saints, shorter than the first one. The Saints named are the Virgin Mary, the Archangels, John the Baptist, the same Apostles as above, the martyrs Stephen, Saturninus, Savinus, Protus, Januarius, the bishops Martin and Gregory, Galdinus, Charles and Ambrose. This also concludes with a Collect, which specifically refers to St Gregory. “Infirmitatem nostram respice, omnipotens Deus, et quia pondus propriae actionis gravat, beati Gregorii Pontificis tui intercessio gloriosa nos protegat. Per.

–Look upon our infirmity, almighty God, and since the weight of our actions beareth heavy upon us, may the glorious intercession of Thy bishop Gregory protect us.”

The deacon hebdomadary then intones another responsory.

R. Rogamus te, Domine Deus, quia peccavimus tibi; veniam petimus, quam non meremur; * manum tuam porrige lapsis, qui latroni confitenti paradisi januas aperuisti. V. Vita nostra in dolore suspirat, et in opere non emendat, si exspectas, non corripimur, et si vindicas, non duramus. Manum tuam... –R. We beseech Thee, o Lord God, because we have sinned against Thee; we ask for forgiveness, which we do not deserve. * Stretch forth Thy hand to the fallen, Thou who didst open the doors of paradise to the thief that confessed. V. Our life suspireth in sorrow, and emendeth not in works; if Thou await us, we are not reproved, and if Thou take vengeance, we cannot endure it. Stretch forth...

Twelve Kyries are sung once again, followed by the Agnus Dei, alternated between the readers and the maceconici.

V. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

R. Gloria Patri. Sicut erat.

V. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

R. Sucipe deprecationem nostram, qui sedes ad dexteram Patris.

V. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

R. Kyrie, eleison. Kyrie, eleison. Kyrie, eleison.

The standard conclusion of most Ambrosian ceremonies is said, after which the canon observer (“observator”), who will serve as hebdom the following week, says the Votive Mass for penance, at which the Archbishop preaches.

![]() |

| St Charles Borromoeo leading a procession with the relic of the Holy Nail during the great plague which struck Milan in 1576-7. St Gregory the Great originally introduced the Greater Rogations at Rome to beg God’s mercy and the end to a plague. (Painting by Giovan Mauro della Rovere, also known as “il Fiamminghino - the little Fleming”, since his father was born in Antwerp.) |

This was supposed to be published yesterday, but my internet service decided it was taking the evening off. Thanks once again to Nicola for his help.![]()

![]()