Back in December, I posted a short review of a new book from Angelico Press, Roger Buck’s The Gentle Traditionalist. (Have a look at that review if you are interested in a more general description of the book.) At the time, I promised to follow up later on with a few specifically liturgical thoughts.

Some passages in the book struck me as highly pertinent to the plight of the sacred liturgy today. Early on, we discover that one of the characters, Anna, has abandoned the New Age movement for traditional Catholicism and a vocation to the religious life — to the bewilderment of her former lover, Geoffrey Peter Luxworthy, who is still very much in love with her. He muses at length about her inexplicable conversion:

Although at this juncture in the story the characters are talking about the wider problem of the modern creed of secular relativism, the observation here is strikingly applicable to the liturgical question. The 1960s marked a turning point, a watershed moment. Although there were liturgical modernists well before that decade, it was only then that the above-described mentality firmly entrenched itself — namely, that whatever in the realm of liturgy was said and done and believed before the 1960s is always wrong and that what is being said and done and believed now is always right. Everyone who felt or thought (or feels or thinks) differently is wrong: they are stuck in the past, they have not caught up with modernity and its new insights and requirements. Prior to the 1960s, there was a long line of Popes who spoke with great determination and seriousness about the normativity of Catholic tradition, the immense respect due to it, and the danger of innovation and experimentation. During and after the 1960s, tradition had become a bad word, respect for it a sign of spiritual regression or mental feebleness. Proponents of liturgical revolution were able to prevail based on a fundamental premise that was never allowed to be challenged.

In this vein, the Gentle Traditionalist says to his interlocutor:

But isn’t all this talk of blood, sacrifice, adoration, penance (one could easily add many other words to the list) redolent of an old-fashioned perspective that Modern Man, with all his progress and science, simply cannot share any more? Ah, that’s the whole problem in a nutshell. There is the truly Christian worldview and there is the distinctively modern worldview, and the two have nothing to do with each other. They are, in fact, totally opposed to each other, as opposed as Christ and Antichrist. Buck sees this opposition in terms of sacramental or non-sacramental, tradition or rationalism:

These are only a few snippets from the book, which again I recommend for its well-rounded and humorous treatment of the problem of modernity and the necessity of a “counterrevolutionary” response to it. Buck has shown convincingly, in the form of a dialogue of ideas, why a compromise with the anti-natural, anti-traditional, anti-sacramental spirit of modernity is impossible and has been, in fact, the root cause of our present malaise. It comes down to rationalism (the mental disease introduced by an era we would do well to call “the Endarkenment”) or tradition (which bears in itself the true enlightenment brought by Christ). Like water and oil, they can be blended with violence but they do not mix and must eventually separate.

Click here for The Gentle Traditionalist's page at Angelico Press.

Click here to order from Amazon.com.![]()

Some passages in the book struck me as highly pertinent to the plight of the sacred liturgy today. Early on, we discover that one of the characters, Anna, has abandoned the New Age movement for traditional Catholicism and a vocation to the religious life — to the bewilderment of her former lover, Geoffrey Peter Luxworthy, who is still very much in love with her. He muses at length about her inexplicable conversion:

Nor could I understand why she wanted to go to a Mass in a dead language. From what I understood, the Catholic Church had changed the Mass when it liberalised itself in the1960s. This liberalisation looked like a good thing to me. But Anna thought the changes in the Church were slowly killing it. Since the ’60s, she told me, there’d been massive declines in vocations — as well as Catholic baptisms, marriages, etc. People were abandoning the Church in droves. She was particularly worried that very few people bothered with Confession anymore. The new liturgy, according to her, was a major part of the problem. Apparently, a “mystic life-force” was being drained from the Church. (pp. 25-26)As the story continues, Geoffrey (GPL) meets a mysterious character called the Gentle Traditionalist.

GPL: It is indeed odd to find you here. In fact, I’ve been wanting someone to help me understand the exact issues you describe: those which separate modern, liberal people, as you call them, from conservatives. I’ve met this conservative type — a woman. Really, I cannot understand half the things she’s talking about.This phrase has haunted me ever since I read it: some people have been culturally denied the keys to understanding the Faith and its traditional practices. This is not to say that unbelievers have no personal responsibility, that all can be blamed on the surrounding culture. It is but a sobering acknowledgment that so many people, even within the Church, have never been given the basic “means to understand” what she is talking about in her doctrine, what she is doing in her rites. Very few (comparatively speaking) are deeply, intimately familiar with the teaching, life, and rituals of the Church in their preconciliar fullness and clarity. This is why reading older authors for the first time can bring us up short: “I cannot understand half the things she’s talking about … her views are completely unintelligible.” We see the dynamics of rupture and discontinuity at work.

GT: Yes — your culture never provided you the means to understand.

GPL: Well, I don’t know about that…

GT: You’re intelligent, educated — and yet her different views are completely unintelligible to you. There must be a reason. Is it not possible you’ve been culturally denied the keys to understanding? (p. 38)

GT: Well, the 1960s are just a handy approximation. Although some people are even more specific than that. They identify 1968 as the turning point. But think about what I’m saying: Wherever previous generations disagree with the post-1960s worldview — let’s call it that for short — previous generations are always wrong. Post-’60s is always right. At least, according to modern media and education.

Post-’60s says a woman has a so-called “right to choose.” Post-’60s must be right; everyone who felt differently, before the ’60s, is obviously wrong.

Or take freedom of speech. Only the other day, someone told me pornography was “the price we have to pay” for free speech. All kinds of people say that — now. Nobody ever said that before the ’60s. Westerners believed in freedom of speech in 1950, too. Still, they banned things like Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence. Literature was prohibited — to say nothing of pornography. But according to the post-’60s worldview, freedom of speech means pornography should be allowed everywhere. Why didn’t people ever think that before the ’60s? […]

If you belong to the New Secular Religion, the 1960s revelation is your creed, your Bible. Every generation of people before you, who believed differently, was wrong. In other words: wherever pre-’60s beliefs differ from post-’60s ones, post-’60s is always, always right. (p. 47)

|

| Free Speech Movement, UC Berkeley, November 20, 1965 |

Only the material world counts in the New Secular Religion. Either no other world exists or it if it does, it doesn’t matter. It counts for nothing. You have a materialist metaphysic — either de jure or de facto… It’s the same with all religions. Buddhists don’t believe in God. Inevitably, that helps form their ethics. Christians do believe in God — a personal God—and their ethics are formed by that. Secular Materialists don’t believe in an afterlife and that, likewise, shapes their ethics. (p. 51)As many have noted, Catholics today, due to a powerful desire to accommodate themselves to the secular world, to be welcomed by it and “competitive” with it, run the serious risk of imbibing the materialist metaphysic, the New Secular Religion, and even reproducing and reinforcing it in and through their corporate acts. Sadly, we cannot exclude the causal influence of a worship that no longer confronts them with and immerses them in otherworldliness, the primacy of the invisible, inaudible, transcendent, as underlined by rich symbols of the sacred, hallowed chant, hidden ritual, and reservoirs of silence. If most Catholics in the contemporary West have the mentality of secular materalists, must we not resolutely and fearlessly look to the root causes of this debacle, and not be content with a superficial prognosis?

In this vein, the Gentle Traditionalist says to his interlocutor:

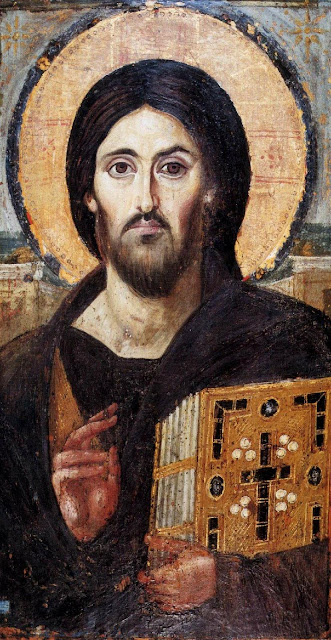

[T]he English often have the whole idea of the Church mixed-up. You think it’s a place where someone preaches a sermon, you sing some hymns, maybe say a prayer or two. Then come home again. For Catholics, that’s a travesty of the Church! I warned you this wouldn’t be PC — but it’s the tragedy of the English-speaking world. Millions and millions of English people — also Americans, Australians, etc. — they all think a church is somewhere you gather on Sundays for spiritual instruction. Rules! … The Reformation never took hold in most countries like it did in England. So this state of confusion doesn’t exist in Greece or Russia or Spain. Plus, in some countries, they use separate words for Protestant and Catholic sites of worship. But in English, it’s just one word — church — for two entirely different realities. To your ordinary American, a church is something like a meeting hall — an assembly room! To a Catholic, it’s a place where the most sublime ritual on Earth is enacted.That the Mass itself has been reduced in the minds of many to a community gathering for songs and homilies — as evidenced by the relative emphasis given to each of the parts in many celebrations today — only sharpens the point Buck is making: the Protestant notion of “church” and “church service” has massively invaded the Catholic sphere, to the point where it is almost unknown that the Mass is primarily an oblation of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ to the glory and praise of the Most Holy Trinity, a propitiatory sacrifice on behalf of the living and the dead, and only secondarily an occasion for instruction and fellowship. One might put it this way: the Mass is pleasing to God and sanctifying for man because of its inherent nature as the unbloody renewal of the all-sufficient sacrifice of Calvary, the fruits of which we share in Holy Communion; its didactic and social functions are premised on that sacrifice, ordered to it, and derived from it.

But isn’t all this talk of blood, sacrifice, adoration, penance (one could easily add many other words to the list) redolent of an old-fashioned perspective that Modern Man, with all his progress and science, simply cannot share any more? Ah, that’s the whole problem in a nutshell. There is the truly Christian worldview and there is the distinctively modern worldview, and the two have nothing to do with each other. They are, in fact, totally opposed to each other, as opposed as Christ and Antichrist. Buck sees this opposition in terms of sacramental or non-sacramental, tradition or rationalism:

GT: … Clearly, I advocate Sacramental societies over non-Sacramental societies. If you study traditional Catholic cultures, capitalism does not develop so strongly. Likewise, you don’t see the same hyper-individualism, atomisation of society, breakdown of the family, social decay… Unfortunately, today’s Church doesn’t understand the power of its own Sacraments. Or sacramentals — like this Holy Water or the Rosary. This is the tragedy of the post-Vatican II Church. Large parts of it have surrendered to faith in rationalism, rather than keeping faith in tradition. The Church must recover her tradition. Only tradition understands the immense, healing power of the Sacraments. That power can save civilisation. If people returned to Confession, if people took the Mass seriously again, there’s no telling what would happen. But how can ordinary people take those things seriously, when the priests and bishops don’t either? (p. 161)American Catholics are blessed with many priests and bishops who take the sacraments seriously, which might prompt one to think the Gentle Traditionalist guilty of exaggeration. If one looks to the dire European scene (as this book does), however, there is no question of exaggeration. One may indeed wonder if the Son of Man will find any faith left when He returns. Without a doubt, there are still the valiant who cling to the Church, her sacraments, and her sacramentals, but they can see their societies and their churches crumbling around them. In our times, to continue to be supernaturally hopeful and to persevere in the faith despite appearances and a lack of institutional support is a form of heroism that may well produce the great saints of the end times.

[T]he Church has been given the power to resurrect. Resurrection applies not only to individuals, but also society. The Sacramental Church has the power to resurrect society, but it must claim it once more. That’s why Benedict XVI — against considerable opposition — was working to restore the liturgy. (p. 162)Exactly: the Church cannot take anything for granted; her earthly leaders must claim her power and use it, rather than being embarrassed or afraid or reticent or too sophisticated. I am reminded in this connection of something often stated and experienced by Juventutem groups: If only the Church’s leaders would bring forth the treasures of tradition with pride, joy, and generosity, spreading them as a banquet before the starving men and women of our profaned world, all would see their immense sanctifying and evangelizing potency. It can already be seen in the places where the “experiment of tradition” has been attempted without any artificial restrictions.

These are only a few snippets from the book, which again I recommend for its well-rounded and humorous treatment of the problem of modernity and the necessity of a “counterrevolutionary” response to it. Buck has shown convincingly, in the form of a dialogue of ideas, why a compromise with the anti-natural, anti-traditional, anti-sacramental spirit of modernity is impossible and has been, in fact, the root cause of our present malaise. It comes down to rationalism (the mental disease introduced by an era we would do well to call “the Endarkenment”) or tradition (which bears in itself the true enlightenment brought by Christ). Like water and oil, they can be blended with violence but they do not mix and must eventually separate.

Click here for The Gentle Traditionalist's page at Angelico Press.

Click here to order from Amazon.com.