↧

Fostering Young Vocations

↧

A Victoria Mass in Palo Alto, CA, for Candlemas

On Candlemas, the St. Ann Choir, directed by Stanford Musicology Professor, William Mahrt, (President of the Church Music Association of America, and Editor of the journal Sacred Music), will sing the Missa Quarti Toni by Tomás Luis de Victoria, along with the propers for the Feast. The Mass will be followed by the Blessing of the Candles and a Candlelight Procession. The Ordinary Form Mass will be sung in Latin at St Thomas Aquinas Church in Palo Alto, California, at the address and time in the poster below.

↧

↧

Fostering Young Vocations (Part 2)

Yesterday I posted an old photograph of a young boy dressed as a priest and playing at saying Mass, with another boy acting as his server. I had originally thought to contrast it with the following video, as an example of how the practice of children “playing” at the liturgy is still, God willing, fostering vocations and devotion even in our own day. I had seen the video on facebook some time ago, but its title is in Russian, and I couldn’t track it down in time for yesterday’s post. I am therefore very grateful to reader James Badeaux for giving a link to it in the combox.

Note, by the way, that these children are not playing at celebrating the Eucharistic liturgy, but Matins, complete with incensations. (There is so much we Romans can learn from the East!) The “anointing” (with glue, it seems) is a part of the Byzantine Great Vigil service held on Saturday evenings and the day before the major feasts. The celebrating priest paints a cross of rose-scented oil on the foreheads of the laity, who each kiss his hand. However, the other priests present each take the brush from the celebrant, and paint the oil on their own foreheads; the celebrant and the priests kiss each others’ hands before and after. Also note, therefore, how at 1:53 the boy in the red hat correctly acknowledges his brother’s sacerdotal dignity by kissing his hand and giving him the brush. (Slightly missing the point, he later kisses his own hand.) At the end, the smaller one blesses the people and says, (as one does towards the end of every major Byzantine service) “Mir vsyem - Peace be with you!” And with thy spirit, little brother!

Note, by the way, that these children are not playing at celebrating the Eucharistic liturgy, but Matins, complete with incensations. (There is so much we Romans can learn from the East!) The “anointing” (with glue, it seems) is a part of the Byzantine Great Vigil service held on Saturday evenings and the day before the major feasts. The celebrating priest paints a cross of rose-scented oil on the foreheads of the laity, who each kiss his hand. However, the other priests present each take the brush from the celebrant, and paint the oil on their own foreheads; the celebrant and the priests kiss each others’ hands before and after. Also note, therefore, how at 1:53 the boy in the red hat correctly acknowledges his brother’s sacerdotal dignity by kissing his hand and giving him the brush. (Slightly missing the point, he later kisses his own hand.) At the end, the smaller one blesses the people and says, (as one does towards the end of every major Byzantine service) “Mir vsyem - Peace be with you!” And with thy spirit, little brother!

↧

Gregorian Chant Meeting 2015 - London - March 14, 2014

For those in the London area who have a love of Gregorian Chant, or would like to learn more about it, I'd encourage you to check out this event which will be held in a little over a month.

The next meeting of the Gregorian Chant Network will take place on Saturday 14th March, 2015. For the first time it will be open to all. Directors of chant groups registered with the GCN will get a discount.

We will be addressed by Daniel Saulnier, former choirmaster at Solesmes, and Giovanni Varelli, Cambridge researcher who discovered the manuscript of the earliest written polyphonic music, which will be performed at the meeting.

The meeting includes lunch, for those who want it, and concludes with Vespers, followed by tea.

Programme (Subject to minor changes)

10.30 Registration

11.00 Talk by Daniel Saulnier

12noon Angelus and talk by Giovanni Varelli

1pm Lunch

2.30 Joseph Shaw on the GCN

2.45-4pm Rehearsal for Vespers with Daniel Saulnier

4.15 Vespers in the Little Oratory

5pm Tea

Prices: Directors of scholas and chant choirs which are members of the Gregorian Chant Network: £10 including lunch. Others: £10 without lunch; £25 including lunch.

The Latin Mass Society is hosting a booking page here.

↧

A New Child Chorister Program at the San Francisco Oratory-in-Formation

A child chorister program will be starting this spring for boys and girls between 8 and 12 at the San Francisco Oratory-in-formation at Star of the Sea Church, San Francisco. The children admitted into this unique program will be taught the elements of music, modern musical theory and notation, as well as Gregorian Chant and its theory, modes and performance. Emphasis will be placed on learning solfege in order to perfect sight-singing, as well as rhythmic training. Special emphasis will be placed on voice production and training. The eventual goal of the Chorister Program will be to supply singers for one of the Sunday morning Masses at Star of the Sea Church. The program is under the pedagogical auspices of the Royal School of Church Music. This is a splendid opportunity for a musical education for your child which the parish offers free of charge. Homeschooling parents can receive music/arts credits for the class in most programs. Interested parents should call the parish office on 415.221.8558 or email at sfchoristers@yahoo.com, to make an appointment to meet the director, Jeffrey Morse, and for a very short audition, primarily to ascertain that your child is able to match pitch. Classes will begin in March, exact date to be announced once auditions have ended.

↧

↧

A Beautiful New Altar in a Soon-to-be-Dedicated Church (Mary Help of Christians, in Aiken, SC)

As we reported last week, the church of St Mary, Help of Christians in Aiken, South Carolina, will be dedicated next Monday, the feast of Candlemas, by His Excellency Robert Guglielmone, Bishop of Charleston. The architectural firm that designed the church, McCrery Architects, and Fr Gregory Wilson, the pastor, both sent us photographs of various parts of the church building, the decorations and furnishings, which you can see by clicking here; the whole project is worth seeing as an example of a brand new church which is built in complete respect for the Catholic tradition of sacred art and architecture. McCrery has just sent me several photographs of the various phases of the project to design and build the altar, (a project which took about 11 months from initial idea to execution), which I am happy to be able to share with our readers.

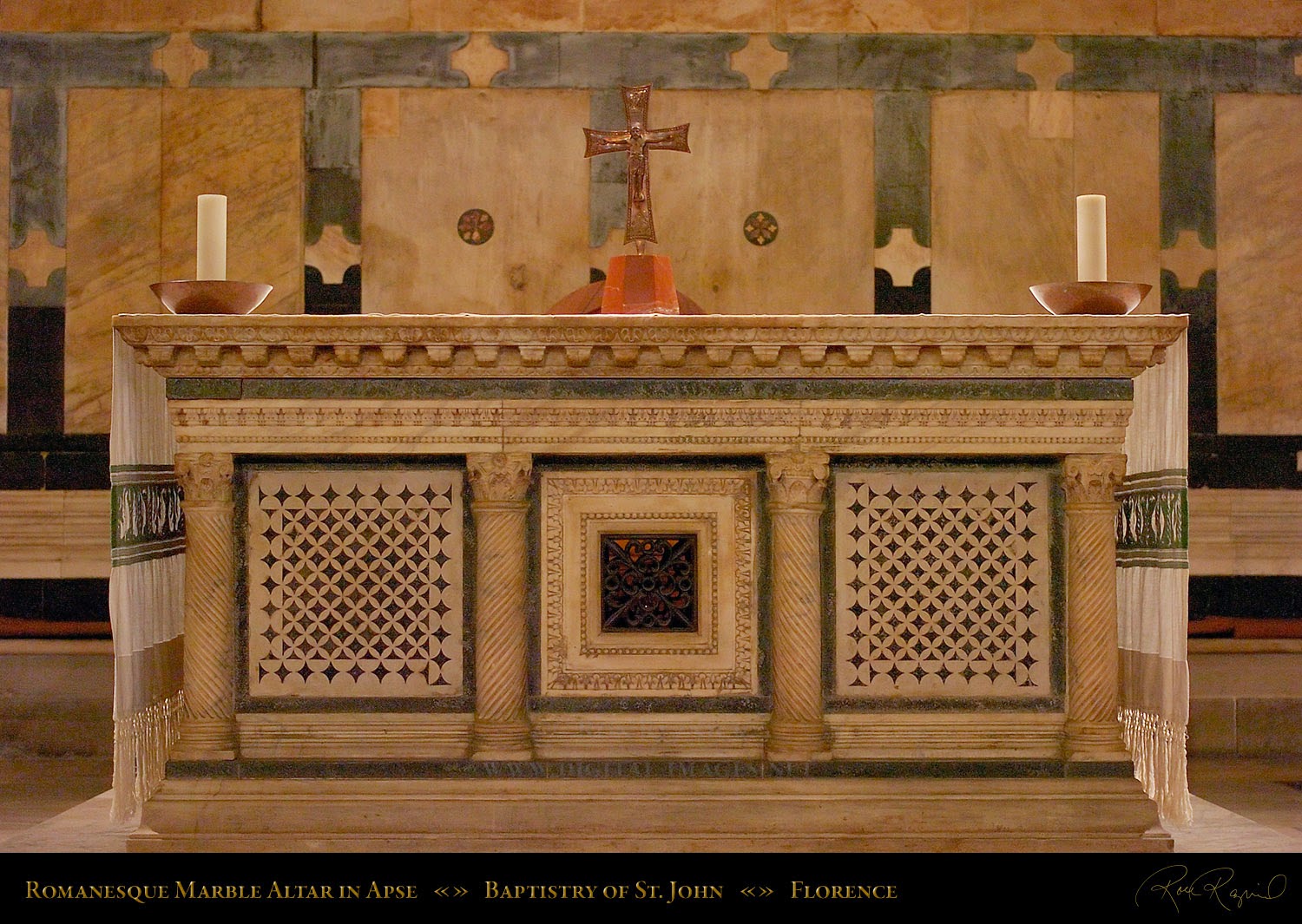

The altar of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral was chosen by Fr Wilson as the starting point for the project:

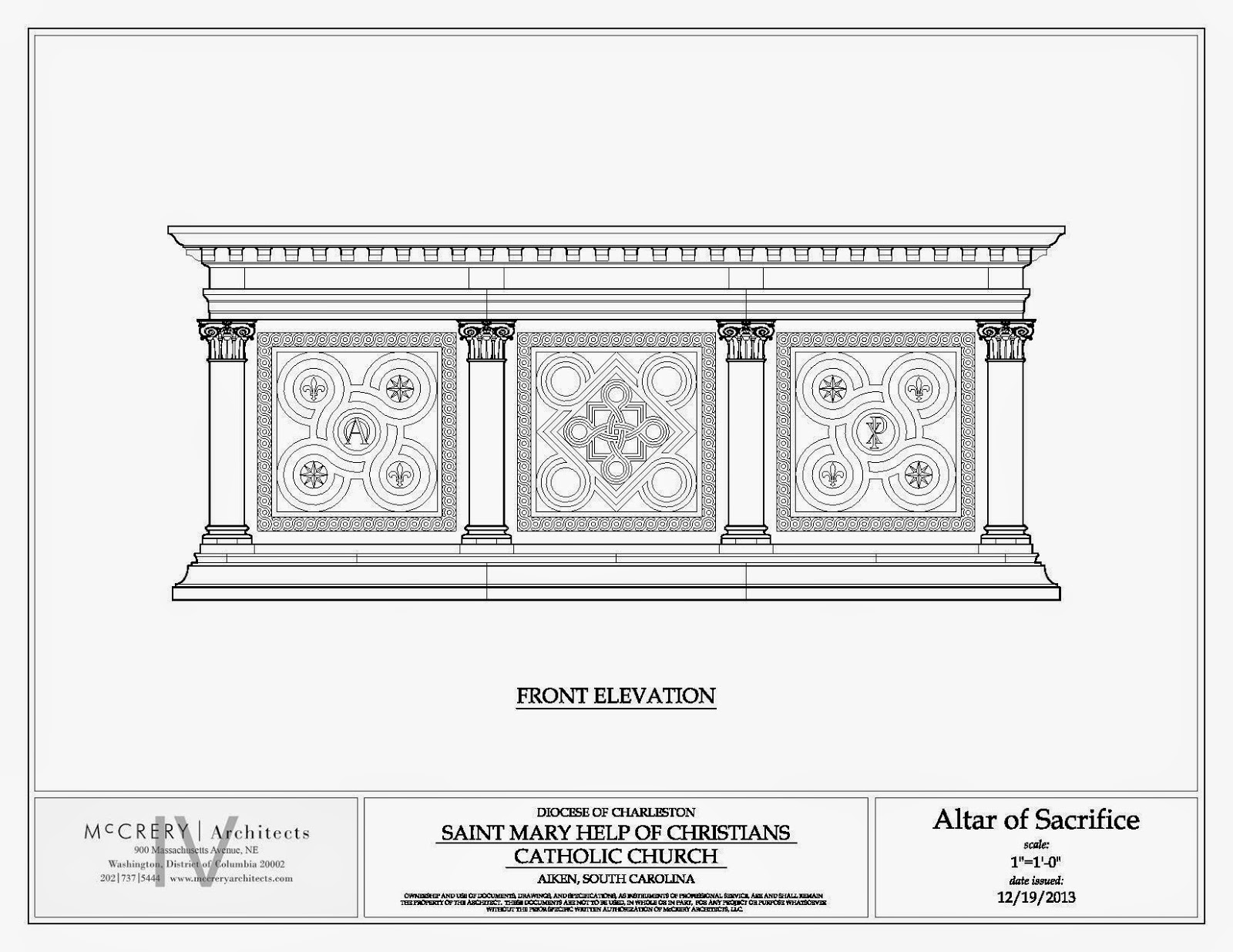

The final approved drawing for the altar design.

The seven species of marbles employed in the altar. The one on the upper left was later replaced with a much whiter specie that forms the body of the altar and mensa.

Color studies using color pencils, which are later sent to the fabricator’s shop.

One of the round colonnettes that support the mensa – notice the concrete block altar core in the background.

The altar of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral was chosen by Fr Wilson as the starting point for the project:

The final approved drawing for the altar design.

The seven species of marbles employed in the altar. The one on the upper left was later replaced with a much whiter specie that forms the body of the altar and mensa.

Color studies using color pencils, which are later sent to the fabricator’s shop.

Fabrication begins: small inlay pieces cut by computer-guided water-jet now ready for assembly.

Front panel assembly

Bringing it all together - altar front assembly.

One of the round colonnettes that support the mensa – notice the concrete block altar core in the background.

The altar core being wrapped with the marble assemblies.

The completed altar, installed over three days.

↧

Farewell to the Alleluia

Today is Saturday before Septuagesima, and Roseanne Sullivan has an article on Dappled Things about the custom of bidding farewell to the Alleluia on this day:

![]()

I began thinking about Septuagesima yesterday because I was a little surprised that this pre-Lenten season is upon us already. Blogger Veronica Brandt drew my attention to this imminent change of seasons by posting a little video yesterday on “Farewell to Alleluia” on the Views from the Choir Loft blog, which showed some of her five children using puppets to sing Alleluias as a way to say “goodbye to the Alleluia.” She wrote, “In the Extraordinary Form tomorrow is Septuagesima, or (roughly) the 70th day before Easter, where all alleluias are suddenly taken away.” You may be wondering, “What does that mean, that all Alleluias are suddenly taken away? And what’s this about singing goodbye to the Alleluia?”

In 1969, the Septuagesima season was removed from the liturgical calendar and its three Sundays and two week days were absorbed into Ordinary time. Even though I was raised a Catholic and attended Mass for years before the liturgical calendar was changed, I only heard about Septuagesima maybe six years ago, and I’m still finding out what it means. For me, as I’m sure is true for others, writing about a subject is the best way to learn about it. It’s a rich topic, and I can just barely scratch the surface, but here goes with a little introduction to Septuagesima, for those who live in an ordinary time world or those who, like me, worship according to the traditional calendar, but just haven’t been paying attention.

Continue reading this article at Dappled Things. . .In 1969, the Septuagesima season was removed from the liturgical calendar and its three Sundays and two week days were absorbed into Ordinary time. Even though I was raised a Catholic and attended Mass for years before the liturgical calendar was changed, I only heard about Septuagesima maybe six years ago, and I’m still finding out what it means. For me, as I’m sure is true for others, writing about a subject is the best way to learn about it. It’s a rich topic, and I can just barely scratch the surface, but here goes with a little introduction to Septuagesima, for those who live in an ordinary time world or those who, like me, worship according to the traditional calendar, but just haven’t been paying attention.

↧

Is the Liturgy an End or a Means? Further Considerations

After seeing the post “A Fundamental Misunderstanding of the Nature of the Catholic Liturgy,” a reader wrote to me about her experiences in a certain religious community that seemed to embody this very misunderstanding. She gave her permission to share the letter as long as I did not reveal any names or dates. First, then, for her story:

All of these phrasings share, at root, a Protestant rejection of the Incarnation as a mystery that irrupts into time and space and becomes living and real for us in and through the sacred liturgy, which is the very gate of heaven, our access to and participation in the heavenly Jerusalem. The fact that most Western liturgies look and feel nothing like the heavenly Jerusalem suggests the extent to which we have bought into Protestant iconoclasm, anti-sacramentality, anti-bodiliness, and Eucharistic indifferentism. A solemn and beautiful celebration of the usus antiquior is, indeed, a taste of heaven—as it should be. If one cannot forget oneself in the liturgy, one has not yet even begun to pray. I mean this in the sense of the Byzantine chant: “Let us who mystically represent the cherubim and sing the thrice-holy hymn to the life-giving Trinity now set aside all earthly cares.”

The world, like the poor, we will always have with us; but Christ the Lord, in our mystical encounter with Him in the holy oblation, we do not (so to speak) always have with us; we are not always engaged in liturgical divine worship, and that is why, when we are so engaged, it must count. It must be right, holy, God-oriented, a total immersion in His life, death, and resurrection. The focus is all on Him.

That point about “not being Benedictines,” too, is striking, since Benedictine spirituality has long been recognized and praised as simply the natural unfolding of the supernatural vocation of the Christian. Every Christian, to the extent he can, ought to be a sort of Benedictine. I realize not everyone would agree with this formulation, but it could be demonstrated from the Holy Rule that all of its author’s general principles are taken from the New Testament or are directly extrapolated from it. For example, let nothing be put before the Work of God. Can anyone honestly say, even if he’s a Jesuit, that caring for the bodily needs of the poor ought to take precedence over the worthy praise of God Himself and the conferring of His life-giving sacraments? By all means, take care of the poor—but do not neglect “the one thing necessary” for the rich and for the poor!

Those who understasnd that the lex orandi is the first and fundamental expression of the Christian faith will understand what true obedience in the Church means: it means keeping alive in every generation the mission of Christ and the apostolic seed, receiving what has been passed down, cherishing and embracing it, and making it fruitful in the world and for the future. But if the liturgy is relegated to a secondary position, what then is going to take its place? What will be the source and summit of the Christian life? It’s up in the air: it could be apostolic work or the field hospital, it could be theology, it could be endless conferences and meetings and synods, it could be anyone’s idiosyncratic version of Christianity. It seems to me that everything hinges on whether one takes liturgy to be a goal that orders everything else around it or a mere “form” of life—that is, a means to a different goal.

For [x] years I was a religious sister … During my years with them at various convents, I had difficulty with the way they spoke of the Liturgy, and likewise I had difficulty with the way the Liturgy was carried out. Among the many philosophical distinctions made in homilies, classes, and chapters, the one I heard most often was that the Liturgy is “at the level of the Form, not at the level of the Finality.” Another way they put it was that the Liturgy is “secondary.” This word “secondary” seemed to translate as “not too important.”This writer has eloquently said what is wrong with putting the liturgical adoration of God in a secondary or compromised position. There is such a temptation to relegate liturgy to an incidental, a stepping-stone, a means, a mindset, an incentive, a mere symbol of what is greater—however one wishes to put it.

It seems there were many consequences to such a view, although I’m not sure whether they are all direct consequences. I’ll list a few of the consequences I had in mind. Liturgies were planned at the last minute. Silence during the Mass was often preferred to music (during times which traditionally require music, such as an Introit, an Offertory proper or Communion proper). If they did have music, it was a skeletal version of Gregorian Chant which had been translated into the vernacular and stripped of its melismas in the name of “purity” … The walls of their chapels were blank white …

My fellow religious would readily admit, with a laugh, that our Divine Office was poor, but in the next breath they would often explain, “but we are not Benedictines. Liturgy is not first in our life.” Some referred to the Benedictines as “liturgical Pharisees.” Even art itself was spoken of as being merely “at the level of the form.”

Today, I help run a choir and schola at a parish. I’m so edified by the way our priest treats every detail of the Liturgy with such great attention and care, as if he were dealing with our Lord Himself. Even so, I still run into people who criticize our efforts at making the Liturgy beautiful. One person recently said to me “Our Lord said ‘make a joyful noise,’ not ‘make a beautiful noise.’ Your expectations of the Liturgy are much too high compared with us normal people.”

I could list many other sad comments, which seem to me stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of the Catholic Liturgy, just as you said. It seems there are many different ways this misunderstanding manifests itself.

All of these phrasings share, at root, a Protestant rejection of the Incarnation as a mystery that irrupts into time and space and becomes living and real for us in and through the sacred liturgy, which is the very gate of heaven, our access to and participation in the heavenly Jerusalem. The fact that most Western liturgies look and feel nothing like the heavenly Jerusalem suggests the extent to which we have bought into Protestant iconoclasm, anti-sacramentality, anti-bodiliness, and Eucharistic indifferentism. A solemn and beautiful celebration of the usus antiquior is, indeed, a taste of heaven—as it should be. If one cannot forget oneself in the liturgy, one has not yet even begun to pray. I mean this in the sense of the Byzantine chant: “Let us who mystically represent the cherubim and sing the thrice-holy hymn to the life-giving Trinity now set aside all earthly cares.”

The world, like the poor, we will always have with us; but Christ the Lord, in our mystical encounter with Him in the holy oblation, we do not (so to speak) always have with us; we are not always engaged in liturgical divine worship, and that is why, when we are so engaged, it must count. It must be right, holy, God-oriented, a total immersion in His life, death, and resurrection. The focus is all on Him.

That point about “not being Benedictines,” too, is striking, since Benedictine spirituality has long been recognized and praised as simply the natural unfolding of the supernatural vocation of the Christian. Every Christian, to the extent he can, ought to be a sort of Benedictine. I realize not everyone would agree with this formulation, but it could be demonstrated from the Holy Rule that all of its author’s general principles are taken from the New Testament or are directly extrapolated from it. For example, let nothing be put before the Work of God. Can anyone honestly say, even if he’s a Jesuit, that caring for the bodily needs of the poor ought to take precedence over the worthy praise of God Himself and the conferring of His life-giving sacraments? By all means, take care of the poor—but do not neglect “the one thing necessary” for the rich and for the poor!

Those who understasnd that the lex orandi is the first and fundamental expression of the Christian faith will understand what true obedience in the Church means: it means keeping alive in every generation the mission of Christ and the apostolic seed, receiving what has been passed down, cherishing and embracing it, and making it fruitful in the world and for the future. But if the liturgy is relegated to a secondary position, what then is going to take its place? What will be the source and summit of the Christian life? It’s up in the air: it could be apostolic work or the field hospital, it could be theology, it could be endless conferences and meetings and synods, it could be anyone’s idiosyncratic version of Christianity. It seems to me that everything hinges on whether one takes liturgy to be a goal that orders everything else around it or a mere “form” of life—that is, a means to a different goal.

|

| Going to meet Christ, the Light of the World |

↧

Dominican Rite Mass for First Saturday Devotion (SF Bay Area, 2/7/15)

|

| First Saturday Mass |

The first Missa Cantata will be at St. Albert the Great Priory Chapel, 6172 Chabot Road, Oakland CA, 94618, this Saturday, February 7, at 10:00 a.m. Confessions will be heard in the chapel from 9:30 to 9:50 before Mass, and recitation of the Marian Rosary will follow immediately. Visitors and guests are welcome; pew booklets with the text of Mass in Latin and English will be provided. There is ample parking on the street and in the priory lot.

↧

↧

Liturgical Notes on the Purification of the Virgin Mary

The medieval liturgical commentator William Durandus, writing at the end of the 13th century, describes the Purification as a “double feast.”

Its connection with Christmas is expressed most clearly at First Vespers of the feast, at which the antiphons are repeated from the Octave of Christmas. Each of them speaks of the Virgin specifically in reference to the Savior’s birth, as for example the second, “When Thou wast born ineffably of a Virgin, then were the Scriptures fulfilled; Thou camest down like the dew upon the fleece of wool, to save the human race; we praise thee, our God!” In the Breviary of St. Pius V, these are sung with the Vesper psalms for feasts of the Virgin, but in other places, the psalms of Christmas Vespers were used instead. At Liège and elsewhere, the Lauds hymn from the Office of Christmas, A solis ortus cardine, was sung at these Vespers in place of the Marian hymn Ave Maris Stella. In many churches, the liturgical color of the Christmas season, white, was used in the Masses of the season for the period between the octave of Epiphany and the Purification, and the use of green began only after February 2nd. (At Paris, this custom continued until 1870.)

The liturgy also formally marks the Purification as the end of the whole cycle of celebrations that form the first part of the Church’s year. On the first Sunday of Advent, the Postcommunion begins with the words, “May we receive (suscipiamus) Thy mercy, Lord, in the midst of Thy temple”, while the Introit of the Purification, citing Psalm 47 more exactly, begins with the verb in the indicative: “We have received (suscepimus), o God, Thy mercy, in the midst of Thy temple.” This change indicates that what we asked for and awaited in Advent has been fully received in the Birth of Christ.

It should also be noted that the earliest possible date for Ash Wednesday is February 4th. (This has not occurred since 1818, and will not occur again until 2285.) The Christmas cycle, including the preparatory season of Advent, will therefore always be separated from the Easter cycle, including the preparatory season of Lent, by an interval of at least one day.

In regard to Him that is born, the feast is called “Hypapante”, that is “the meeting” (in Greek), because in that solemnity Anna the prophetess and Simeon met the blessed Mary as She came into the temple to offer Her Son, Christ. … The Lord’s coming into the temple signifies His coming into the Church, and into the mind of each faithful soul, which is a spiritual temple. The Lord foretold this coming through the prophet Malachi, “Behold, I send my Angel before thy face etc.” (chap. 3, 1-4, the epistle of the feast.) Secondly, in regard to Her that gave birth, it is also called the feast of the Purification, because the Blessed Virgin, although She had no need of purification, and was not held liable to the law of purification, … wished nevertheless to fulfill the precept of the Law (in Leviticus 12, 1-8. Rationale Divinorum Officiorum 7.7)This precept states that 40 days after giving birth, a woman “shall bring to the door of the tabernacle of the testimony, a lamb of a year old for a holocaust, and a young pigeon or a turtle for sin, and shall deliver them to the priest, who shall offer them before the Lord.” For this reason, the Purification serves as the formal end of the Christmas season, being celebrated exactly forty days after it.

|

| The Presentation in the Temple, by Pieter Jozef Verhaghen, 1767; Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent, Belgium |

The liturgy also formally marks the Purification as the end of the whole cycle of celebrations that form the first part of the Church’s year. On the first Sunday of Advent, the Postcommunion begins with the words, “May we receive (suscipiamus) Thy mercy, Lord, in the midst of Thy temple”, while the Introit of the Purification, citing Psalm 47 more exactly, begins with the verb in the indicative: “We have received (suscepimus), o God, Thy mercy, in the midst of Thy temple.” This change indicates that what we asked for and awaited in Advent has been fully received in the Birth of Christ.

It should also be noted that the earliest possible date for Ash Wednesday is February 4th. (This has not occurred since 1818, and will not occur again until 2285.) The Christmas cycle, including the preparatory season of Advent, will therefore always be separated from the Easter cycle, including the preparatory season of Lent, by an interval of at least one day.

In the later 4th century, the pilgrim Egeria wrote, in her famous account of her visit to the Holy Land, that the Meeting of the Lord with Simeon in the Temple was celebrated there with particular solemnity, “just as at Easter”, forty days after Epiphany. In her time, the Epiphany commemorated all the events of the Lord’s birth, and the Meeting was therefore originally kept on February 14th; this arrangement is still observed to this day in the Armenian Rite. When the feast of Christmas was adopted in the East shortly after (and in some places, even before), the eastern Epiphany was made to focus on the Lord’s Baptism; the Meeting, as an event of His infancy, was then moved back to February 2nd, counting the forty days from December 25th.

It is often stated that when it was introduced to the West in the mid-to-late 7th-century, the Meeting became a Marian feast, whereas the East continued to observe it as a feast of the Lord. (See, for example, the relevant entries in the old Catholic Encyclopedia, the revised Butler’s Lives, and Bl. Schuster’s The Sacramentary; the last refers quite incorrectly to its “predominantly Marian character.”) This arises from a rather superficial analysis of its liturgical title and texts. It is true that its Latin name appears very early as “the Purification of the Virgin Mary”, as, for example, in the Gelasian Sacramentary and the Murbach lectionary, both of the mid-8th century. It is also true that it was considered a Marian feast in the Middle Ages. But its character as a “double feast”, and one of Greek origin, was never forgotten; about a century before Durandus, Sicard of Cremona wrote, “Today’s is therefore a double solemnity, of Her that gives birth, and of Him that is born, that is of the Mother and the Son; in regards to the Mother, it is called ‘the Purification’, in regard to the Son, ‘Hypapante’, which is interpreted ‘the Meeting.’ ” (Mitrale 5.11)

The traditional Roman Mass of the Purification refers to the Virgin only where She is mentioned in the Gospel, and almost parenthetically in the Postcommunion. Likewise, the rites that precede the Mass refer to Her once in the first prayer for the blessing of candles, (again, almost parenthetically), and twice in the processional antiphons. The double character of the feast noted by Sicard and Durandus is more clearly expressed in the Office, many parts of which are taken from the common for feasts of the Virgin. However, even here, the invitatory, lessons and responsories of Matins, and the Lauds antiphons, (also used at remaining Hours), all refer to the Meeting of Christ with Simeon.

According to the Liber Pontificalis, Pope St Sergius I (687-701) established that a procession from the church of St Adrian in the Roman Forum to Saint Mary Major, on the Annunciation, the Dormition and Nativity of the Virgin, and the “feast of St Simeon”. Born in Sicily, but of Syrian origin, this Pope was certainly familiar from his youth with the liturgies of both the Byzantine and Latin tradition. There is good evidence that a procession with candles was associated with the feast from an early date, as Butler’s Lives also notes, but it died out entirely in the East; where it is done today in a few Eastern churches, it is a fairly recent Latinization. There is no mention of candles in the Liber Pontificalis’ words about Pope Sergius, nor in the early Roman liturgical books; the first reference to a blessing of candles on February 2nd is found in the late 10th century.

first of these is borrowed from the Byzantine Liturgy; the second is from the day’s Gospel.

.jpg) |

| A 15th-century Russian icon of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple |

The traditional Roman Mass of the Purification refers to the Virgin only where She is mentioned in the Gospel, and almost parenthetically in the Postcommunion. Likewise, the rites that precede the Mass refer to Her once in the first prayer for the blessing of candles, (again, almost parenthetically), and twice in the processional antiphons. The double character of the feast noted by Sicard and Durandus is more clearly expressed in the Office, many parts of which are taken from the common for feasts of the Virgin. However, even here, the invitatory, lessons and responsories of Matins, and the Lauds antiphons, (also used at remaining Hours), all refer to the Meeting of Christ with Simeon.

According to the Liber Pontificalis, Pope St Sergius I (687-701) established that a procession from the church of St Adrian in the Roman Forum to Saint Mary Major, on the Annunciation, the Dormition and Nativity of the Virgin, and the “feast of St Simeon”. Born in Sicily, but of Syrian origin, this Pope was certainly familiar from his youth with the liturgies of both the Byzantine and Latin tradition. There is good evidence that a procession with candles was associated with the feast from an early date, as Butler’s Lives also notes, but it died out entirely in the East; where it is done today in a few Eastern churches, it is a fairly recent Latinization. There is no mention of candles in the Liber Pontificalis’ words about Pope Sergius, nor in the early Roman liturgical books; the first reference to a blessing of candles on February 2nd is found in the late 10th century.

first of these is borrowed from the Byzantine Liturgy; the second is from the day’s Gospel.

Aña Adorn thy bridal chamber, o Sion, and receive Christ the King. Embrace Mary, who is the gate of heaven, for she bears the glorious King of the new light. She remains a virgin, as she brings forth in Her hands the Son, begotten before the day-star; whom Simeon taking into his arms, proclaimed to peoples to be is the Lord of life and death and the Savior of the world.As the procession enters the church, one of the responsories of Matins is sung; note the clever way the repetition of the verse completes the doxology at the end.

Aña Simeon had received an answer from the Holy Ghost, that he would not see death, before he had seen the Anointed of the Lord; and when they were bringing the Child into the temple, he received Him in his arms, and blessed God, saying, “Now dost thou dismiss thy servant, O Lord, in peace. V. When His parents were bringing Jesus, to do according to the custom of the Law for Him, he took Him in his arms.

R. They offered for Him unto the Lord a pair of turtle-doves, or two young pigeons * As it is written in the law of the Lord. V. And after the days of Mary’s purification were fulfilled, according to the law of Moses, they brought Him to Jerusalem, to present Him to the Lord. As it is written. Glory be. As it is written.The historical Roman tradition was to use violet vestments for the procession, and white for the Mass who follows on returning to the church. Lit candles are held by the clergy and faithful (as much as may be practically allowed) during the procession, at the singing of the Gospel, and from the Canon to communion.

Many improbable attempts have been made to connect the Candlemas blessing and procession with the ancient Roman purification rite of the Lupercalia. The Venerable Bede says that the Roman King Numa dedicated February to the god Februus, another name for Pluto, “who was believed to have power over rites of purification,” and established it as a month of various rites to religiously purifie the city. (The name of both the month and the god derive from “februare – to purify.”) Bede then says that the Christian religion changed “this custom” for the better (without mentioning the Lupercalia specifically) by instituting a procession with candles in its place “in the same month, on the day of St Mary”. (De temporum ratione XII, PL XC col. 351)

The Lupercalia are mentioned repeatedly by other Church Fathers, and even at the end of the fifth century, Pope St Gelasius I felt the need to combat some vestiges of its celebration. A race though the city that formed part of the festival was still being run, and the Pope sarcastically suggests in a letter to a Roman senator who defended the practice that the runners should return to the more ancient practice, and go naked. Bede’s idea becomes more tempting as an explanation for the procession’s origins when one considers that the Lupercalia were celebrated from February 13th to the 15th, coinciding with the Purification’s original Eastern date; and further, that the name of the Christian feast that begins the ancient Roman month of purification was changed to “the Purification” in Rome.

For all this, however, it is extremely unlikely that any vestiges of the pagan rite remained in the time of Pope Sergius, who instituted the procession almost two centuries after Gelasius, and not for the Purification alone, but for all the Marian feasts. Rome had suffered in the meantime a significant depopulation during the plagues and wars of the 6th century, which dealt a massive blow to the city’s ancient customs and institutions. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that the feast was never kept in the West on any date other than February 2nd.

The Lupercalia are mentioned repeatedly by other Church Fathers, and even at the end of the fifth century, Pope St Gelasius I felt the need to combat some vestiges of its celebration. A race though the city that formed part of the festival was still being run, and the Pope sarcastically suggests in a letter to a Roman senator who defended the practice that the runners should return to the more ancient practice, and go naked. Bede’s idea becomes more tempting as an explanation for the procession’s origins when one considers that the Lupercalia were celebrated from February 13th to the 15th, coinciding with the Purification’s original Eastern date; and further, that the name of the Christian feast that begins the ancient Roman month of purification was changed to “the Purification” in Rome.

For all this, however, it is extremely unlikely that any vestiges of the pagan rite remained in the time of Pope Sergius, who instituted the procession almost two centuries after Gelasius, and not for the Purification alone, but for all the Marian feasts. Rome had suffered in the meantime a significant depopulation during the plagues and wars of the 6th century, which dealt a massive blow to the city’s ancient customs and institutions. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that the feast was never kept in the West on any date other than February 2nd.

|

| The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, mosaic by Jacopo Torriti, 1296, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome |

↧

Announcing the Way of Beauty Online Course for 3 College Credits

For artists, for architects, for priests and seminarians, for educators, for all undergraduates!

Have you ever wondered why this painting by Vermeer is still admired by so many centuries after it was painted?

Or why a painting like Christ Crowned with Thorns by the 15th century Italian artist Fra Angelico can draw thousands of people to an art exhibition in the 21st century?

Yet they blew this building up less than 50 years after it was built?

Why do you think this 18th-century mass housing has become a holiday destination...

while few wanted even to walk close to this 20th century mass housing, let alone live there, even a decade after it was built?

A significant reason, I suggest, is that the beauty in their forms, or the lack of it, makes them desirable or undesirable and this in turn affects their utility. Beauty and utility are inseparable. The form of these paintings and buildings are reflections of the worldview of those who created them, which are in turn a manifestation of the culture of the society they lived in. Although not all the were made for the liturgy, the forms are profoundly connected to how people in that society worship, as with the whole culture, for this is what shapes all that we believe most powerfully.

If you want to understand how all these things are connected, and how the forms of Western culture are connected to the way in which a society worships and most profoundly the Sacred Liturgy, then you you will find answers in the online course, the Way of Beauty, which can now be taken for college credit.

The Way of Beauty online has been available since the Fall in reduced form for audit or continuing education units. I have now expanded and enhanced the material for college credit, so that it is a much more thorough and deep investigation into the roots of Western culture. It is accredited by Thomas More College of Liberal Arts and is available through www.Pontifex.University. Mine are the first courses for this new education platform which has been created to provide courses that guarantee fidelity to the teachings of the Church in every course it offers.

Have you ever wondered what exactly connects the cosmos to the liturgy and Western culture? Or how, precisely, the patterns of musical harmony, the cosmos and the liturgy are connected to the proportions of beautiful buildings and paintings?

Would you like to know how to be formed, or to educate others, to apprehend and create beauty as great artists always were in the past; and why should this formation should be part of every education?

The photograph above is of a college chapel at Cambridge University. Do you know why they made a college chapel look more beautiful than a modern Catholic cathedral, and spent so much time making even the libraries of colleges beautiful in the past? It is not simply ostentatious display, as some might suggest, it is linked directly to a deep understanding of the nature of education.

If these are the sorts of questions that you think about when you look at, for example, the contrast between modern and traditional cultures, then I think you are going to find this course fascinating. The course draws on the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and Church Fathers from Boethius, Augustine and Aquinas through to Newman, John Paul II and Benedict XVI...and on the methods and practices of those who have created objects of beauty through centuries.

For more information feel free to contact me through this website, or go to the Online Courses page on my blog, thewayofbeauty.org or go direct to the Catalog at www.Pontifex.University.

This is so much more than an art history course...it does precisely what the Church tells us all education should: an 'integral formation through a living encounter with a cultural inheritance' The Catholic School, 26, pub Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education

For those who wish to read further here, the following is the information as it appears on my website:

The Way of Beauty: for artists, for architects, for priests and seminarians, for educators, for all undergraduates who want to understand what forms the culture. An ideal formation for anyone who wants a formation in beauty, to understand the basis of Western culture and to contribute to a new epiphany of beauty!

3 College-level transferable credits, accredited by Thomas More College of Liberal Arts, just $300 per credit

This is the most thorough and complete presentation yet of how to follow the via pulchtritudinis, to teach others how to do it too and transform the culture in the process! Includes detailed material available for the first time and which is not available anywhere else.

So much more than an art history course...it does precisely what the Church tells us such a course should and so it will affect the whole of your education: it offers an 'integral formation through a living encounter with a cultural inheritance' [The Catholic School, 26; pub the Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education, 1977.]

You will receive a foundational overview of the great Catholic tradition of art and architecture, so that you understand how the forms are connected to the theological and philosophical outlook of each artist and the society from which he came. As such it also gives you deep understanding of what forms a whole culture of beauty.

It draws on a tradition that starts with the ancient Greeks, with figures such as Pythagoras and Plato, through the Church Fathers, such as Boethius and Augustine, to the more recent writings of Bl John Henry Newman, St Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI. For all these writers the good life has been equated with the beautiful life. This course teaches you how to live that life of transforming beauty.

- 13- videos produced with Catholic TV in which we explore how form is shaped by theology and philosophy - watch the first one for free here

- A four part e-book, The Way of Beauty: Liturgy, Education, Art and Inspiration written exclusively for the course. See a chapter by chapter summary here: Contents.chapter.by.chapter

- 18 fascinating and attractively produced half hour videos giving you chronologically presented history of art and architecture in the West from the ancient Greeks to the present day.

- Plus longer video presentations of the connection between the pattern of religious life and the cosmos; and how modern astrophysics reinforces the ancient understanding of the cosmos.

Who is it for?

It is designed to accompany and enrich all other educational programs:

It is for all undergraduate students as part of a general core or Catholic studies program. You will understanding of what constitutes the essence of a Catholic culture and why this is essential to any Catholic education no matter what your major.

It is or high school students seeking college level credit before going to college.

It is for all those who love and want to help create a beautiful culture. If you love art, architecture and music and want to know what makes these or indeed any aspect of the culture Catholic; if you who wish to know how we can reestablish a culture of beauty in the West and wish to contribute to it creatively in any discipline, then you will love this course too.

For artists who are looking for a formation that accompanies the skills they are learning elsewhere. This offers a formation that will enhance their creativity and understand how to make their work more beautiful.

For architects and architecture students who want to gain a thorough understanding in how to incorporate traditional harmony and proportion into what they do, and why this will make their buildings more beautiful.

For patrons of the arts and especially priests and seminarians who are in a position to affect the whole culture profoundly by patronizing beautiful art and architecture in our churches.

For all teachers and educators, and anyone involved in adult formation this will give you a deep understanding of why a formation in beauty is an essential aspect of every Catholic education and then teach you how to pass on that formation to your students.

How is it taught?

We provide the information through 34 video presentations and detailed reading material attractively presented and which was written especially for this course. You develop your understanding through interactive online discussion groups in which students and teachers communicate, and quizzes that test understanding and allow you to ask follow up questions if you do not understand the answers. The grading is done via a series of essay questions in a mid-term and final exam. All is done in your own time and at your own pace.

What topics does it cover?

The course contains both a conventional art history course, which works chronologically through the main developments in Western art from the ancient Greeks to the present day; and a course that teaches you how to connect the changing worldviews through these periods to the actual forms of the culture. You will understand why modern art looks different from ancient Greek art and why both are different to the Baroque of the 17th century. Then by extension these arguments are applied to the culture as a whole and through this the student will understand what shapes culture, what constitutes a Catholic culture and how we can re-establish a culture of beauty in the West. In not only informs people about beauty, culture and art and architecture, it also forms them so that can apprehend beauty more readily. It explains the essential aspects of a formation in beauty, so that people grow in love for what is beautiful, become more creative and can be open to inspiration.

Of special interest to many will be my most detailed description yet of the numerical basis for traditional harmony and proportion, in which the student is taken right back to those sources which shaped the tradition including Plato, Aristotle, Boethius, Augustine as well as the scriptural basis for such ideas. There is an examination of their application through the centuries by consideration of, for example, the works of Vitruvius, Alberti and Palladio in the field of architecture. Through this the student will understand the common thread that runs through all that is ordered and beautiful. He will understand how the same numerically describes patterns are reflected in time and space and run through the whole culture. We see, for example, the same numerical patterns in the rhythms for living and of our worship in the sacred liturgy; we see them too in the structure of the cosmos at all levels of scrutiny from particle physics to astrophysics; and see these patterns in traditional Western culture.

For those who are aware of my book, co-written with Leila Lawler, the Little Oratory, A Beginner's Guide to Prayer in the Home, this is a much deeper exploration of the theology and theories which are the foundation of the practices of prayer and worship it describes. It is the soundness of its foundation in the Faith that caused Scott Hahn to describe the book as follows: 'This is one of the most beautiful books I've ever seen. It is inspiring yet practical, realistic yet revolutionary. If one book has the potential to transform the Catholic family (and society), this is it.'

Other areas of study are:

- Cult and culture: how culture in general is derived from our worship and why it is the strongest influence on is in our formation and our education, bar none - not social factors, not economics, not politics.

- The Catholic traditions in figurative art with case studies on a number of paintings in each figurative tradition. You will know, for example, what makes the gothic, the baroque and the iconographic styles distinct; and what connects them so that each tradition is appropriate for the liturgy. We contrast and compare these with the forms of art that reflect modern philosophy and from traditional non-Christian cultures.

- Creativity, Intuition and Love These are the fruits of a traditional education in beauty. It develops us as people so that we have more ideas and better ideas and can grasp the relationship between particulars and the whole in any context better. It also increases our capacity to love God and man and our inclination to do so. This is demonstrated not only by reference to the traditional understanding of these things, but also to modern scientific research which supports the points made. While this is presented as a discussion about these topics as subjects to learn, we provide guidance also to those who wish to become more creative, intuitive and loving by actually practicing and experiencing the principles described.

The Way of BeautyTM, SM is a service mark and trade mark wholly owned by David Clayton and cannot be used by others except with his permission.

↧

A Tradition Both “Venerable” and “Defective”: More from Matthew Hazell on the Reform of the Missal

I posted an article at the beginning of December, noting the important work of Mr Matthew Hazell in documenting the changes to the Postcommunion prayers, in both the Latin originals and the various English translations. He has just added to his site Lectionary Study Aids a page with links to two scanned articles from Ephemerides Liturgicae, both from 1971, which provide quite a bit of useful information on certain aspects of the 1969 reform of the Missal. The first, by Henry Ashworth O.S.B., is a brief description of the reform of the Prayers for the Dead in the new Missal; the second is in French, by Antoine Dumas O.S.B., and gives the sources for the abundance of new prefaces added to the Missal in the Novus Ordo.

As one might expect, knowing something of the procedures by which so much of the post-Conciliar reform was done, what these articles document is not lacking in irony. For example, Dom Henry tells us that “those whose task it was to compose these prayers were not unmindful of the rich theology of life and death contained in the ancient formularies of the Mozarabic liturgical books, especially in the Oracional Visigótico.” (Edited by J. Vives and published at Barcelona in 1946, in the series Monumenta Hispaniae Sacra.) An examination of his footnotes reveals that that this “rich theology” was grossly impoverished by addressing several of its prayers directly to Christ. These were therefore rewritten for incorporation into the Novus Ordo, in accordance with the entirely false theory that all liturgical prayers were anciently addressed to the Father.

Likewise, Dom Antoine tells us (section 4) that “Too many beautiful texts remained unused in the ancient Sacramentaries,” (which is quite true), and that these must serve as the first source for the new prefaces to be added to the Missal. He goes on to say that “(t)he criteria for selection had to be rigorous, to obey the directives of Vatican II, which had defined the liturgical reform first of all as a response to pastoral needs.” I agree that broadening the corpus of Prefaces was in theory a good idea, although I am not convinced that it was a particularly urgent pastoral problem; Sacrosanctum concilium itself is completely silent on the matter. Since the texts of this “venerable tradition” had to be both “translatable into modern languages, and adapted to the modern mentality”, very few of them could be retained in their entirety, according to Dom Antoine. They required “numerous cuts, and a patient work of centonization,” (composing new texts out of fragments of various old texts); otherwise, “reproduced in their original form, they would be unbearable, if not defective.” (insupportables, sinon fautifs.)

As one might expect, knowing something of the procedures by which so much of the post-Conciliar reform was done, what these articles document is not lacking in irony. For example, Dom Henry tells us that “those whose task it was to compose these prayers were not unmindful of the rich theology of life and death contained in the ancient formularies of the Mozarabic liturgical books, especially in the Oracional Visigótico.” (Edited by J. Vives and published at Barcelona in 1946, in the series Monumenta Hispaniae Sacra.) An examination of his footnotes reveals that that this “rich theology” was grossly impoverished by addressing several of its prayers directly to Christ. These were therefore rewritten for incorporation into the Novus Ordo, in accordance with the entirely false theory that all liturgical prayers were anciently addressed to the Father.

Likewise, Dom Antoine tells us (section 4) that “Too many beautiful texts remained unused in the ancient Sacramentaries,” (which is quite true), and that these must serve as the first source for the new prefaces to be added to the Missal. He goes on to say that “(t)he criteria for selection had to be rigorous, to obey the directives of Vatican II, which had defined the liturgical reform first of all as a response to pastoral needs.” I agree that broadening the corpus of Prefaces was in theory a good idea, although I am not convinced that it was a particularly urgent pastoral problem; Sacrosanctum concilium itself is completely silent on the matter. Since the texts of this “venerable tradition” had to be both “translatable into modern languages, and adapted to the modern mentality”, very few of them could be retained in their entirety, according to Dom Antoine. They required “numerous cuts, and a patient work of centonization,” (composing new texts out of fragments of various old texts); otherwise, “reproduced in their original form, they would be unbearable, if not defective.” (insupportables, sinon fautifs.)

↧

Pontifical Mass at the Throne in Madison: Candlemas 2015

On Feb 2, 2015, Bishop Robert Morlino celebrated a pontifical Mass at the Throne following the blessing of candles, as part of an going project where he celebrates Pontifical Masses in the Extraordinary Form every one to two months.

The schola sung gregorian propers, Mass IX Cum jubilo, Credo III (sung by the congregation and schola unaccompanied), Ave Maris Stella (chant), Hodie Beata Virgo Maria (Sheppard) and Alma Redemptoris Mater (Juan García de Salazar). Photos by James Howard, Roland Scott, and myself. Full album can be found here.

↧

↧

Dominican Rite Blessing of Ashes with Low Mass

|

| Blessing of Ashes, Holy Rosary, Portland OR (2014) |

See image to left above where, last year, Fr. Steven Maria Lopez, O.P., Prior of Holy Rosary Priory, Portland OR, is blessing the ashes at a table on the Epistle Side. He is assisted by servers of the parish and the celebrant, Fr. Vincent Kelber, O.P., parochial vicar. In this ceremony, which I on which I have already written this post, the Blessing involves various chants, beginning, after the Seven Penitential Psalms, with the antiphon Ne Reminiscaris and its verses and collect, the Absolution, the blessing itself, and the imposition of ashes, during which other antiphons are chanted. The Mass then begins with the return of the ministers who omit the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar. The priest ascends, kisses the altar, makes the silence Sign of the Cross, and goes to read the Officium (Introit) at the book. Those interested in the Solemn form to compare it to the Roman may consult the previously mentioned post.

It is probably best, should ashes have already been blessed for the parish or priory, to use those ashes blessed earlier and skip the blessing. The Dominican imposition ceremony could, of course be used. But, should there be reason to bless new ashes at a Low Mass, a couple of problems arise when the ceremony is conducted without music by a priest alone with only one server. Fortunately, the Missale Ordinis Praedicatorum (1965), p. 40, resolves some of the questions, but on at least one it is silent.

First a question not related to the music, what if there is no prior (or pastor) available to bless the ashes? In fact, the Dominican Missal assumes the presence of a Dominican community and therefore a prior or, at least, a superior. But there is rubric that resolves this. It reads, I translate:

- If the solemn blessing of ashes is done separately [i.e. not connected to the Penitential Psalms], it is permitted to bless the ashes in the morning using a simple form, without the Penitential Psalms and without chant. This form can be used even where the sacred ministers [i.e. deacon and subdeacon] and chants cannot be found.

1. In preparation, a covered table is placed on the Epistle side at the foot of the steps. On it would be the container with ashes and the holy water with sprinkler.

2. The priest vests, as the prior would have, in surplice and stole (unlike the Roman, no cope is worn in our rite for this or the Asperges---although this might be done pro causa solemnitatis, but that Romanism is not my choice). The server, carrying the Missal, leads the priest to the altar. The customary reverence (bow or genuflection) is made. They go to the table, where the priest faces the table and altar, and the server stands to the left side of the table facing the priest (as the deacon would in the solemn form). The priest opens the book (servers do not do this in our rite).

3. The priest reads the blessing Omnipotens sempiterne Deus, with the server responding. The priest then sprinkles the ashes with holy water. Those who want to read this blessing my consult the post already mentioned.

|

| The Celebrant Assists with Giving Ashes (Portland, 2014) |

4. After bowing to the cross or tabernacle, the priest and server go to distribute ashes to the people. If there is a priest available to impose ashes on the celebrant, this should be done first. The priest uses the traditional Dominican formula: Meménto quia cinis es, et in cínerem revertéris ("Remember that you are ashes, and to ashes you will return"). I think it suitable that the server follow after the priest, sprinkling each recipient with holy water, as the celebrant would do when the prior distributes ashes in the solemn imposition.

5. The priest and server then return to the altar and bow. The server drops off the holy water on the little table and takes the Missal. Both make the customary reverence and go to the sacristy.

6. While the priest vests for Mass, the server returns, makes the customary reverence, and removes the little table with the ashes and holy water. He then returns to the sacristy to pick up the Missal and precede the priest to the altar. It is possible, I guess, to have the veiled chalice already on the altar, but that would really follow Solemn Mass rubrics, not those of Low Mass or even of the Missa Cantata.

At this point an unaddressed issue arises. At a Dominican sung Mass, the chalice is prepared between the Epistle and Gospel, by the subdeacon at Solemn Mass or by the priest himself at a Missa Cantata. In the Low Mass of 1962, the preparation of the chalice comes before the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar. When Mass follows the blessing of ashes, those Prayers are omitted. In the 1965 Missal, there was no problem because, by then, the chalice preparation had been moved to the Roman position at the Offertory in all Masses. But this was not true in 1962. So, unless there is an older friar reading this who remembers differently, I would suggest the following be done:

7. The server, carrying the book, leads the priest, with the chalice and his amice covered capuce up, to the altar. They make the customary reverence. The priest ascends to the altar, uncovers the chalice, opens the corporal, and goes to the Epistle side to prepare the chalice. The server meanwhile has placed the Missal on the stand, and retrieved the cruets. The priest makes the chalice. He then goes to the center and lowers his capuce.

8. The server having taken his place on the Gospel side opposite the Missal, the priest makes the silent Sign of the Cross and goes to the book to read the Officium (Introit) and Kyrie. The Mass then continues as usual. Note, however, that the Flectamus genua precedes the Opening Collect and that the Prayer over the Faithful is added after the Postcommunion (as on all ferials in Lent). Since 1960, the extra collects (found in the 1933 Missal) are omitted, and the Benedicamus Domino is replaced by the Ite missa est, unless a ceremony immediately follows after Mass, which would not happen today.

I hope that friars who have the opportunity to bless ashes and say the traditional Dominican Low Mass this Ash Wednesday find this helpful.

Also remember that a Dominican Rite Mass of the Immaculate Heart will be celebrated this Saturday in Oakland CA as announced here.

↧

The Legend of St Agatha

Like many of the ancient virgin martyrs, Saint Agatha was made to suffer for the faith because she refused to marry a pagan who wished to marry her. In her case, it was a man of consular rank named Quintianus, who tried to use the Emperor Decius’ edict of persecution against her. The story of her martyrdom is summed by thus by the 1529 Breviary of the Roman Curia, the predecessor of the Breviary of St Pius V. When Agatha was sent to prison, after various torments and interrogations,

The words on the plaque described above in Latin are “Mentem sanctam, spontaneam, honorem Deo, et patriae liberationem.” They are a grammatical fragment, consisting of three nouns in the accusative (objective) case, and their modifiers, without a verb or subject. “Spontaneam” can be read as if it modified “mentem”, but the Blessed Jacopo da Voragine in the Golden Legend explains the inscription thus. “It means ‘She had a holy mind, she offered himself willingly, she gave honor to God, and brought about the liberation of the fatherland.’ ”

These words were set to music, and commonly sung as the antiphon for the Magnificat at First Vespers of the feast of St Agatha. This antiphon was removed from the Roman Breviary in the Tridentine reform, which also no long mentions the plaque or the angel in the Matins lessons; it was retained, however, by the Dominican and Cistercians. The motive may have been that the story itself was thought to be unlikely, and it is certainly true that the acts of St Agatha are not considered to be historically; on the other hand, it may have been simply because it is a grammatical fragment.

The inscription may also be seen on many church bells, which were often rung to warn people of some impending danger. The blessing of a bell traditionally included a prayer which asked that

This may derive from the tradition that St Agatha repeatedly delivered the city of Catania where she was martyred from the dangers posed by the eruption of Mt Etna, which is also referred in the Golden Legend.

She stretched out her hands to the Lord and said, “O Lord who made and created me, and have kept me from my infancy, … qui took from me the love of the world, who have kept my body from pollution, who made me to overcome the executioner’s torments, iron, fire and chains, who gave me the virtue of patience in the midst of torments, I pray Thee to receive my spirit. For it is time, Lord, that Thou command me to leave this world, and come to Thy mercy. Saying this, she sent forth her blessed spirit. The Christian people, taking away her holy body, set it in a new sepulcher, after anointing it. And when she was being laid to rest, there came a young man dressed in silken garments, … and he entered the place where the holy virgin’s body was being laid, and set there a small marble plaque on which it was written, “A holy mind, willing, honor to God, and the liberation of the fatherland.” And he stood there until the sepulcher was diligently closed, and then departing was seen no more in all the province of Sicily; whence there is no doubt that he was and Angel of God.

|

| St Peter Heals St Agatha in Prison, by Giovanni Lanfranco, 1614 |

These words were set to music, and commonly sung as the antiphon for the Magnificat at First Vespers of the feast of St Agatha. This antiphon was removed from the Roman Breviary in the Tridentine reform, which also no long mentions the plaque or the angel in the Matins lessons; it was retained, however, by the Dominican and Cistercians. The motive may have been that the story itself was thought to be unlikely, and it is certainly true that the acts of St Agatha are not considered to be historically; on the other hand, it may have been simply because it is a grammatical fragment.

|

| An antiphonary from the Franciscan convent of Fribourg, Switerland, 1488, with the antiphon “Mentem sanctam.” (source) |

when its melody shall sound in the ears of the peoples, may the devotion of their faith increase; may all the snares of the enemy, the crash of hail-storms and hurricanes, the violence of tempests be driven far away; may the deadly thunder be weakened, may the winds become salubrious, and be kept in check; may the right hand of Thy strength lay low the powers of the air, so that hearing this bell they may tremble and flee before the standard of the holy cross of Thy Son…(Pontificale Romanum)

|

| The inscription of St Agatha on a bell in the Italian city of Laurino. |

When a year had passed, around the day of (Agatha’s) birth into heaven, a very great mountain near the city burst and belched forth a fire, which coming down from the mountain like a flood, and turning both stones and earth to liquid, was coming toward the city with a great rush. Then the multitude of pagans went down from the mountain and felling to her sepulcher, took the veil with which it was covered, a set it against the fire; and immediately on the day of the virgin’s birth, the fire stood and proceeded no further.This story appears in the Office of St Agatha in the antiphon of the Benedictus.

The multitude of pagans, fleeing to the to the virgin’s grave, and took her veil against the fire; that the Lord might prove that he delivered them from the dangers of the fire by the merits of the blessed Agatha, His Martyr.

| A 13th-century reliquary of the Saint, crusted over with jewels that have been donated to her over the centuries. In her left hand she holds a plaque with the famous inscription on it. |

↧

“Singing through the Liturgical Year” Session 3: Lent

The Church’s hymns are a priceless source of catechesis and inspiration. If you live in or near New York City, you may want to take part in “Singing through the Liturgical Year,” a series to learn about sacred music and to sing (even if you don’t think you have a good singing voice). Father Peter Stravinskas, Ph.D., S.T.D., guides participants through the various liturgical seasons by presenting some of the most popular hymns, in Latin and English, analyzing their theological content and seeking to apply those insights to a life in Christ attuned to the Church’s feasts and fasts. Each session culminates in singing the selected hymns.

The third session of “Singing through the Liturgical Year” concerns the hymns of the Lenten Season and will take place on Thursday, February 19th, at 7:00 pm, at the Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, Parish House, 263 Mulberry Street, Manhattan. Other sessions will be announced throughout the liturgical year.

‟Qui cantat bene, bis orat” (He who sings well, prays twice) — St Augustine

↧

“Balance Instead of Harmony” : A Guest Article by Paweł Milcarek on the History of the Liturgical Reform (Part 2)

We continue with the second part of Dr Paweł Milcarek’s paper on the history of the Liturgical Reform in the pre-Conciliar period, “Balance instead of Harmony.” Click here to read the first part, which was published early last week. Once again, we are grateful to Dr Milcarek for sharing this important wotk with our readers.

![]()

Four personages, four contradictory ideas.

There were plenty of opposing tendencies in what we call the Liturgical Movement in its full bloom, some of them very positive, some which merely seemed so at the time, because their extremism had not as yet had any chance to be exposed.

To examine the existence of those contradictions (which sometimes remain concealed), it is sufficient to compare two leading personages of the Movement: Dom Bernard Capelle on the one hand, and Fr. Josef Jungmann on the other. They can be seen as the symbols of two different guiding ideas, together with two different atmospheres of reform that result from them.

Dom Bernard Capelle (1884-1961), a Benedictine abbot of Mont-César, “an exquisite scholar and monk”, can be rightly considered a patron of the principle of the organic development of the liturgy. He presented it – in an outstandingly clear manner – in 1949 in his annotations to the project of the reform, prepared for the Pian Commission. The whole of this excerpt is worth citing, especially because the text, due to its original confidentiality, is not very well known today. As Dom Capelle stated:

In the same period, Fr. Josef A. Jungmann (1889-1975), a Jesuit and a professor of pastoral theology from Innsbruck, had just published his monumental, two-volume work Missarum Sollemnia (1948), which almost immediately made him an authority on liturgical matters and allowed him to have an increasing influence over liturgical reforms later in the 1950s. Erudite in historical issues, Fr. Jungmann expressed in his publication the conviction that the greatness of the Roman rite consists in that which is ancient in it. However, this assessment may also have its negative and disquieting aspect; it is easy to conclude that which more recent necessarily diminished the Roman Rite. Fr. Jungmann did indeed accept this as a logic conclusion, as he distinguished the noble core of the primitive rite from the “secondary” additions, especially those of the medieval period or later. In one of his main works, first published in 1958, Fr. Jungmann was gentle, but at the same time explicit on the matter:

Fr. Jungmann was certainly too a competent historian not to see and not to admire the phenomenon we called the organic development of the liturgy. The difference between him and Dom Capelle was that he did not consider this natural law of development to be also a principle of the reform – on the contrary, one could say that he regarded the reform as a remedy for this too unconstrained mechanism of growth. Hence on the eve of the Council he openly stated that what we need instead of an “imperceptible growth” is “a jerk – more than a jerk”.

Both Capelle and Jungmann desired the reform of the liturgy, but – as we can see – their opinions even on its principles were simply contradictory. Their concepts of refrom differed not in terms of radicalism, but on a much deeper level, in their very essence. Once we realize this, we are able to foresee real tensions – or even hidden contradictions – which later emerge in the Second Vatican Council’s later constitution on the liturgy of the, since both of them had significant impact on its content.

From personages who were above all the spokesmen for particular ideas, we must now move to those who also held some “political” authority while working on the reform’s documents, as members of ecclesiastical bodies appointed to prepare the liturgical reform, both in times of Pius XII and during the Second Vatican Council. Without any hesitation I would indicate two such personages: Fr. Ferdinando Antonelli O.F.M. and Fr. Annibale Bugnini C.M.

Fr. Ferdinando Antonelli (1896-1993) was a historian and an expert in Christian archeology, as well as a trusted member of the Historical Section of the Congregation of Rites. It was he who – together with Fr. Josef Löwe – edited the above-mentioned Memoria sulla Riforma Liturgica. Fr. Antonelli brings before us as a guiding idea of the reform a firm option for the liturgical reeducation of the faithful. As someone deeply involved in such modifications of the rite as the reform of the Holy Week services, he of course appreciated such retouchings of the liturgy, and considered them necessary. His main care, however, was to make deep changes within the mentality of the faithful, rather than to transform the structures of the rites. At the Assisi Congress in 1956, he clearly stated, while referring to the recent reform of the Holy Week services:

As far as the direction of those revisions is concerned, Bugnini was clear in his support for the rule of so-called pastoral expediencies. In his statements from the 1950s we can easily trace a pragmatic admiration for successful “adaptations to life” – even if some of those movements had the fault of breaking with Tradition, he regarded them as an “indication” that showed some “necessity”. Hence, it is crucial to grasp the idea of adaptation to life in order to understand Bugnini’s attitude. Moreover, according to him there is no need to prove that such a necessity exists; “mere pastoral benefit” is enough to justify brave creations, cuts, and shifts within the ritual.

The course of the liturgical reform – both during the Second Vatican Council and, especially, after its closure – shows that it was shaped in practice rather more by Bugnini’s energy and Jungmann’s ideas. Meanwhile, the deep sense of tradition –represented by Capelle – remained rather quiet, warning against possible abuses; Antonelli’s sober enthusiasm found expression in polishing the outcomes of the others’ efforts.

The testimonies found in the texts and confirmed by the behaviour of the reformers seem to suggest that on the eve of Vatican II, it was more or less consciously agreed that the liturgical reform required balance between various opposing forces to keep the liturgy in the right position. At that time, various pairs of counteracting forces could seen: not only the ideological opposition of the “archaelogists” and the “innovators”, but also the tensions between papal absolutism and the increasing power of the experts, the advocates of worship and the advocates of “pastoral reasons”; the supporters of Roman centralism and the supporters the collegiality; and finally, between the conservatives and the progressives. The balance between them was possible as long as each of these forces played its assigned role, inevitably one-sided and therefore exaggerated. But as soon as one of these major forces ceased to be unambiguously “conservative” or “innovative”, the balance of the whole entity was inescapably threatened, if not destroyed.

However, it is worth mentioning that the concept of balance – usually fragile, changeable, negotiable, reminiscent of constant tug-of-war – may have an alternative, namely the concept of harmony. And harmony is an convergence of factors that may differ in their significance, but together constitute an entity in its whole. Of course, the search for harmony – also in liturgical matters and ministry – does not in itself remove the existence of opposing tendencies and does not exempt us from facing them in debate and in “politics”. But it does offer a different and more reliable measure the naive conviction that the truth is always “somewhere in the middle”. “The ultimate human values (beauty, goodness, love etc.) depend on harmony, rather than on balance”. (Gustave Thibon, L’équilibre et l’harmonie, p. 88.)

To examine the existence of those contradictions (which sometimes remain concealed), it is sufficient to compare two leading personages of the Movement: Dom Bernard Capelle on the one hand, and Fr. Josef Jungmann on the other. They can be seen as the symbols of two different guiding ideas, together with two different atmospheres of reform that result from them.

Dom Bernard Capelle (1884-1961), a Benedictine abbot of Mont-César, “an exquisite scholar and monk”, can be rightly considered a patron of the principle of the organic development of the liturgy. He presented it – in an outstandingly clear manner – in 1949 in his annotations to the project of the reform, prepared for the Pian Commission. The whole of this excerpt is worth citing, especially because the text, due to its original confidentiality, is not very well known today. As Dom Capelle stated:

... nothing is to be changed unless it is a case of indispensable necessity. This rule is most wise: for the Liturgy is truly a sacred testament and monument – not so much written but living – of Tradition, which is to be reckoned with as a locus of theology and is a most pure font of piety and of the Christian spirit. Therefore:The reservations emphasized by Dom Capelle should not be regarded as a conservative obstacle set up against any possibility of reform. The Belgian monk was able to see clearly the connection between the Tradition – hence also the liturgy – and the life, hence also the change. His care was to avoid both “a dead rigidity and an evolutionism which is nothing but another name for decomposition”.

1. That which serves [well] at the present time is sufficient unless it is gravely deficient.

2. Only new things that are necessary are to be introduced, and in a way that is consonant with Tradition.

3. Nothing is to be changed unless there is comparatively great gain to be had.

4. Practices that have fallen into disuse are to be restored if their reintroduction would truly render the rites more pure and more intelligible to the minds of the faithful. (Memoria sulla reforma liturgica: Supplemento II – Annotazioni alla “Memoria”, no. 76, Vatican 1950, p. 9 – as cited in Reid, pp. 162ff.)

In the same period, Fr. Josef A. Jungmann (1889-1975), a Jesuit and a professor of pastoral theology from Innsbruck, had just published his monumental, two-volume work Missarum Sollemnia (1948), which almost immediately made him an authority on liturgical matters and allowed him to have an increasing influence over liturgical reforms later in the 1950s. Erudite in historical issues, Fr. Jungmann expressed in his publication the conviction that the greatness of the Roman rite consists in that which is ancient in it. However, this assessment may also have its negative and disquieting aspect; it is easy to conclude that which more recent necessarily diminished the Roman Rite. Fr. Jungmann did indeed accept this as a logic conclusion, as he distinguished the noble core of the primitive rite from the “secondary” additions, especially those of the medieval period or later. In one of his main works, first published in 1958, Fr. Jungmann was gentle, but at the same time explicit on the matter: