The Norbertine Canons of St Philip's Priory, Chelmsford UK, celebrated the feast day of their Holy Founder St Norbert with a Solemn High Mass sung by the Prior and Superior, Rt Rev Hugh Allan o.praem, who was assisted by Rev Br Stephen Morrison o.praem as Deacon and Preacher.

↧

The Premonstratensians of St Philip's Priory Celebrate Their Patronal Feast

↧

The Feast of the Holy Trinity and Octave of Pentecost 2014

Duo Seraphim clamabant alter ad alterum: * Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth: * Plena est omnis terra gloria ejus. V. Tres sunt qui testimonium dant in cælo: Pater, Verbum, et Spíritus Sanctus: et hi tres unum sunt. Sanctus. Gloria Patri. Plena.

R. The two Seraphim cried one to another: Holy, holy, holy is the Lord, the God of hosts: * All the earth is full of his glory. V. There are three who give testimony in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost. And these three are one. Holy. Glory be to the Father. All the earth.

This responsory was traditionally very prominent in the Divine Office in the Use of Rome, being sung after the eighth lesson of Matins on all the Sundays between the Octave of Epiphany and Septuagesima, and again on the Sundays between the Octave of Corpus Christi and Advent. This custom was introduced by the author of the responsory, Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), under whom the ordo of the Divine Office was written out which would ultimately form the basis of the Breviary of St. Pius V. Odd as it may seem, despite the Trinitarian theme, it was not originally written for or used in the Office of the Holy Trinity, which in Pope Innocent’s time had not yet been received into the Office used at the Papal court; it was only added to the feast in the Tridentine Breviary reform. Several composers have set it to polyphony for use as a motet; among the best of these is the version of Tomás Luis de Victoria.

R. The two Seraphim cried one to another: Holy, holy, holy is the Lord, the God of hosts: * All the earth is full of his glory. V. There are three who give testimony in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost. And these three are one. Holy. Glory be to the Father. All the earth.

This responsory was traditionally very prominent in the Divine Office in the Use of Rome, being sung after the eighth lesson of Matins on all the Sundays between the Octave of Epiphany and Septuagesima, and again on the Sundays between the Octave of Corpus Christi and Advent. This custom was introduced by the author of the responsory, Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), under whom the ordo of the Divine Office was written out which would ultimately form the basis of the Breviary of St. Pius V. Odd as it may seem, despite the Trinitarian theme, it was not originally written for or used in the Office of the Holy Trinity, which in Pope Innocent’s time had not yet been received into the Office used at the Papal court; it was only added to the feast in the Tridentine Breviary reform. Several composers have set it to polyphony for use as a motet; among the best of these is the version of Tomás Luis de Victoria.

↧

↧

Solemn Requiem Mass for Fr Kenneth Walker : Live Broadcast Tomorrow

Tomorrow, Monday, June 16th, the Very Rev. Fr. John Berg, Superior General of the Fraternity of St. Peter, will celebrate a Solemn Requiem Mass for Fr. Kenneth Walker, who was killed at the FSSP house in Phoenix, Arizona, during a break-in this past Wednesday. The Mass will be celebrated in Fribourg, Switzerland, 6:30 PM local time, and broadcast Live on www.LiveMass.net, and on the iMass apps at 11:30 AM Central, 12:30 PM Eastern Time.

Fr. Berg has also written the following letter to the membership and friends of the Fraternity of Saint Peter. (Reproduced from the FSSP website by their kind permission, as is the picture below.)

Fr. Berg has also written the following letter to the membership and friends of the Fraternity of Saint Peter. (Reproduced from the FSSP website by their kind permission, as is the picture below.)

In the midst of mourning for our dear confrere, Fr. Kenneth Walker, one great consolation has been the outpouring of prayers and condolences expressed by so many bishops, religious communities, fellow priests and faithful. Many of you have informed us of the hundreds of Masses which have already been offered for the repose of his soul and for the health of Fr. Joseph Terra. By the grace of God and thanks to your prayers, Fr. Terra’s life is out of danger and we expect him to make a full recovery.

By now you have read on various news outlets and websites about the virtues of Fr. Walker as a priest and how badly he will be missed by his confreres and parishioners. In an age where we seem so centered upon ‘clerical stars’ and are constantly searching for the ‘newest approach to evangelization’, the life of our confrere gave witness to one of the greatest priestly virtues, a quiet and consistent strength, which is a mark of the Good Shepherd who watches vigilantly over his flock in season and out of season.

He has been described by the parishioners he served in the same manner that he would be by his confreres; he was earnest: he was persevering; he was ready first to serve; nothing ever seemed to inconvenience him. Our Lord’s description of Nathaniel perhaps fits him best: he was a man without guile. He will perhaps be remembered as an example to us as confreres more for what he did not say; one would be hard pressed to find anyone who ever heard him complain or speak badly about anyone. As a former professor of Fr. Walker in the seminary, and as superior, I also knew him as one who took correction well; never pridefully objected; and sincerely sought to improve in all areas of formation both as a seminarian and a later as a priest.

In such tragic circumstances I realize that it can be easy to fall into hyperbole, but there was an innocence to Fr. Walker which is rarely found in this valley of tears. His life and his priestly work here below have been cut tragically short – just two short years serving in the vineyard of Our Lord. But we are grateful for the time he had to serve in the Fraternity and that he was given the vocation that he sought. His reason for becoming a priest was already beautifully formulated in his application to the seminary:

By now you have read on various news outlets and websites about the virtues of Fr. Walker as a priest and how badly he will be missed by his confreres and parishioners. In an age where we seem so centered upon ‘clerical stars’ and are constantly searching for the ‘newest approach to evangelization’, the life of our confrere gave witness to one of the greatest priestly virtues, a quiet and consistent strength, which is a mark of the Good Shepherd who watches vigilantly over his flock in season and out of season.

He has been described by the parishioners he served in the same manner that he would be by his confreres; he was earnest: he was persevering; he was ready first to serve; nothing ever seemed to inconvenience him. Our Lord’s description of Nathaniel perhaps fits him best: he was a man without guile. He will perhaps be remembered as an example to us as confreres more for what he did not say; one would be hard pressed to find anyone who ever heard him complain or speak badly about anyone. As a former professor of Fr. Walker in the seminary, and as superior, I also knew him as one who took correction well; never pridefully objected; and sincerely sought to improve in all areas of formation both as a seminarian and a later as a priest.

In such tragic circumstances I realize that it can be easy to fall into hyperbole, but there was an innocence to Fr. Walker which is rarely found in this valley of tears. His life and his priestly work here below have been cut tragically short – just two short years serving in the vineyard of Our Lord. But we are grateful for the time he had to serve in the Fraternity and that he was given the vocation that he sought. His reason for becoming a priest was already beautifully formulated in his application to the seminary:

“God, in His infinite love, desires all men to be saved and so achieve their true end. Along with the Church, then, I am deeply grieved by these errors concerning the nature and dignity of man accepted by so many people in the world, which deviate them from their supernatural end. In full view of the situation in the world, then, the only vocation that I could be satisfied with, as a work, would be one that would be dedicated to bringing people to salvation in whatever way God wills for me to do so.”As confreres we know that Fr. Walker would not want us to waste our time in anger over what has happened; over the gross injustice which has been done. As great as this is a tragedy for us, so too it will bear great graces for our Fraternity: O altitudo divitiarum sapientiæ, et scientiæ Dei: quam incomprehensibilia sunt judicia ejus, et investigabiles viæ ejus! The first grace will be as an encouragement to each of us to take nothing for granted in the call of Our Lord to the Sacred Priesthood. We are His instruments to serve, and must do so always more faithfully in accordance with His will and that of the Church for His greater glory. For the moment let us waste no time, and simply concentrate our efforts in praying for the repose of the soul of Fr. Walker.

We thank the many parishes which have organized Holy Hours and will hold Masses of Requiem on Monday; again, we are humbled by your charity. Fr. Eric Flood, District Superior of North America, will offer a Requiem in Phoenix on Monday in the presence of Bishop Thomas Olmsted, and I will offer one here at the Basilica of Notre-Dame in Fribourg on the same day. The funeral arrangements are on hold until the body of Fr. Walker can be transferred to Kansas. The Fraternity will of course publish these details when they are in place.

|

| Fr. Walker at his first Mass, with Fr. Berg as his assistant priest, in the chapel of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary in Denton, Nebraska. |

↧

Book Review: The Sacred Liturgy, Source and Summit of the Life and Mission of the Church

The Sacred Liturgy, Source and Summit of the Life and Mission of the Church. The Proceedings of the International Conference on the Sacred Liturgy – Sacra Liturgia 2013. Ed. Alcuin Reid. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014. 446 pp.

![]()

Have you ever wished you could bring together a dream team of scholars, pastors, monks, liturgists, musicologists, all of them completely orthodox and totally committed to the sacred liturgy, and then have them commit to writing their finest insights, born of careful study, deep reflection, and pastoral experience? When I attended the Sacra Liturgia conference last summer in Rome (June 25–28, 2013), I found to my immense joy and profit that that was exactly what had been done by the conference’s organizers. The results are now in print for all the world to see, in the form of the complete proceedings of the conference, just published by Ignatius Press.

Publishers are aware that conference proceedings, like the genre of collected essays, are usually hard sells because readers tend to think: “Oh, this is just a random collection, and who can say whether the quality will be high across the board.” Fortunately, in this instance, we have a winner from cover to cover. I recently told a friend in charge of a library that this book is the most comprehensive, eloquent, insightful, hard-hitting, and refreshing volume on the liturgy that I have seen in the past ten years. It is a sheer pleasure to read most of the contents, and profitable to read all of it. The contributors are both clerical and lay, hailing from several continents, bringing their different cultural backgrounds, experiences, and professional expertise to bear on the most pressing (one is sometimes tempted to say intractable) questions of the liturgy in the Church today. These questions include sacred music, church architecture and furnishing, the ars celebrandi, the relationship of the old rite and the new evangelization, weaknesses or errors in the liturgical reform, liturgical formation and catechesis, the role and responsibility of the bishop, the meaning of “pastoral,” the Anglican contribution, the relationship between liturgy and social doctrine, and the canonical structure supporting liturgy.

It would be far too easy to turn this review into a lengthy summary of all the contents, which will be hardly necessary if, trusting my judgment, you get this book and read it yourself. But I cannot refrain from drawing attention to a few addresses that seemed to me particularly luminous and rousing when I heard them in Rome and that strike me as equally magnificent now that I am renewing my acquaintance with them in print.

Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith’s magisterial opening address, “The Sacred Liturgy, Source and Summit of the Life and Mission of the Church” (pp. 19–39) has the virtue of covering just about everything in a cosmic sweep that ranges from creation through Israel and the covenants to the Paschal Mystery of Christ, touching along the way such hot topics as the style of celebration, the use of Latin, the betrayal of the Fathers of the Council, and active participation.

Gabriel Steinschulte’s “Liturgical Music and the New Evangelization” (pp. 41–67) is an entertaining, perceptive, wide-ranging analysis of what has happened to church music and why, and the reasons behind the traditional stance of the Church on chant and polyphony. He sounds a theme that is taken up by several contributors, namely, how the new evangelization relies entirely on a sound, beautiful celebration of the sacred mysteries.

Bishop Peter J. Elliott, famed author of Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite, offers a reflection (pp. 69–85) on the principles of the ars celebrandi as applied to both the old and new forms of the Roman Rite, valuable reading for every celebrant and master of ceremonies. For those keen on liturgical arts, especially the design and arrangement of sacred buildings, the exquisite pieces by Fr. Stefan Heid and Fr. Uwe Michael Lang (pp. 87–114 and 187–211) provide ample nourishment. (My sole criticism of this book is the lack of the diagrams and photos that Fr. Heid and Fr. Lang shared with the conference in Rome to illustrate their arguments. But I do understand that adding a section of illustrations to this volume would have increased its bulk and price, and I also know that one can quickly find images on Google of most, if not all, of the things referred to by the authors; and fortunately, their arguments and descriptions are easy to follow.)

Tracey Rowland’s tour de force of theological anthropology, “The Usus Antiquior and the New Evangelization” (pp. 115–37) is required reading for both those who already know that the traditional Latin Mass is crucial to the Church’s mission in the contemporary world (these will gobble it up), or those who suspect and worry that it might be so (these will come to a sobering realization and then start making plans for learning how to celebrate the EF). Here is a sample of Rowland’s vigorous style:

Archbishop Alexander Sample’s “The Bishop: Governor, Promoter, and Guardian of the Liturgical Life of the Diocese” (pp. 255–71) created a stir at the conference for its comprehensiveness and clarity, bringing into one place all the most important conciliar and post-conciliar magisterial teachings on the precise role and responsibility of the bishop over the liturgy in his diocese—what he is obliged to do and what he should not do. His Excellency then makes a point of addressing Summorum Pontificum and its implications for the ministry of the bishop:

For me personally, the talk that hit me in the gut and left me speechless was Msgr. Ignacio Barreiro Carámbula’s “Sacred Liturgy and the Defense of Human Life” (pp. 371–88). With incomparable candor, detail, and theological acumen, Msgr. Barreiro exposes the relationship between the ravaging of liturgical tradition and the destruction of the family, and how the lack of reverence towards God, especially as present in the mystery of the Mass and the Most Holy Eucharist, has trickled down into contempt for the unborn. His address held no less power for me when I re-read it in the book. An excerpt:

In conclusion, I am willing to say, without the slightest hyperbole, that this book can serve as a kind of charter for the new liturgical movement—and I hope it shall do so.

Publishers are aware that conference proceedings, like the genre of collected essays, are usually hard sells because readers tend to think: “Oh, this is just a random collection, and who can say whether the quality will be high across the board.” Fortunately, in this instance, we have a winner from cover to cover. I recently told a friend in charge of a library that this book is the most comprehensive, eloquent, insightful, hard-hitting, and refreshing volume on the liturgy that I have seen in the past ten years. It is a sheer pleasure to read most of the contents, and profitable to read all of it. The contributors are both clerical and lay, hailing from several continents, bringing their different cultural backgrounds, experiences, and professional expertise to bear on the most pressing (one is sometimes tempted to say intractable) questions of the liturgy in the Church today. These questions include sacred music, church architecture and furnishing, the ars celebrandi, the relationship of the old rite and the new evangelization, weaknesses or errors in the liturgical reform, liturgical formation and catechesis, the role and responsibility of the bishop, the meaning of “pastoral,” the Anglican contribution, the relationship between liturgy and social doctrine, and the canonical structure supporting liturgy.

It would be far too easy to turn this review into a lengthy summary of all the contents, which will be hardly necessary if, trusting my judgment, you get this book and read it yourself. But I cannot refrain from drawing attention to a few addresses that seemed to me particularly luminous and rousing when I heard them in Rome and that strike me as equally magnificent now that I am renewing my acquaintance with them in print.

Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith’s magisterial opening address, “The Sacred Liturgy, Source and Summit of the Life and Mission of the Church” (pp. 19–39) has the virtue of covering just about everything in a cosmic sweep that ranges from creation through Israel and the covenants to the Paschal Mystery of Christ, touching along the way such hot topics as the style of celebration, the use of Latin, the betrayal of the Fathers of the Council, and active participation.

Gabriel Steinschulte’s “Liturgical Music and the New Evangelization” (pp. 41–67) is an entertaining, perceptive, wide-ranging analysis of what has happened to church music and why, and the reasons behind the traditional stance of the Church on chant and polyphony. He sounds a theme that is taken up by several contributors, namely, how the new evangelization relies entirely on a sound, beautiful celebration of the sacred mysteries.

Bishop Peter J. Elliott, famed author of Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite, offers a reflection (pp. 69–85) on the principles of the ars celebrandi as applied to both the old and new forms of the Roman Rite, valuable reading for every celebrant and master of ceremonies. For those keen on liturgical arts, especially the design and arrangement of sacred buildings, the exquisite pieces by Fr. Stefan Heid and Fr. Uwe Michael Lang (pp. 87–114 and 187–211) provide ample nourishment. (My sole criticism of this book is the lack of the diagrams and photos that Fr. Heid and Fr. Lang shared with the conference in Rome to illustrate their arguments. But I do understand that adding a section of illustrations to this volume would have increased its bulk and price, and I also know that one can quickly find images on Google of most, if not all, of the things referred to by the authors; and fortunately, their arguments and descriptions are easy to follow.)

Tracey Rowland’s tour de force of theological anthropology, “The Usus Antiquior and the New Evangelization” (pp. 115–37) is required reading for both those who already know that the traditional Latin Mass is crucial to the Church’s mission in the contemporary world (these will gobble it up), or those who suspect and worry that it might be so (these will come to a sobering realization and then start making plans for learning how to celebrate the EF). Here is a sample of Rowland’s vigorous style:

Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI, Aidan Nichols and other lesser names have argued that the liturgy exists to worship God and that if we promote it for any other reason we are promoting sub-theological ideologies. The most common of these are liturgy as group therapy and liturgy as community building. Nonetheless, it is possible to hold that while the sole purpose of liturgy is worship, there are obvious spiritual and educational side effects and it is in this context that the usus antiquior can play an important role in the New Evangelisation. Specifically, the usus antiquior may be an antidote to the ruthless attacks on memory and tradition and high culture, typical of the culture of modernity, and it may also satisfy the desire of the post-modern generations to be embedded within a coherent, non-fragmented tradition that is open to the transcendent. (p. 117)Alcuin Reid’s contribution, “Sacrosanctum Concilium and Liturgical Formation” (pp. 213–36) is, as we have all come to expect from him, brilliantly incisive and well-documented, as he demonstrates the central role given by the Council Fathers to a genuine immersion in the “spirit and power of the liturgy” that would govern and control all reform and renewal. Sad to say, such a preparation was utterly lacking, which is why the reform went sour and the renewal never happened. Reid urges us to take seriously the Council’s counsel by not neglecting ongoing liturgical formation in our own day, if we would ever surmount the difficulties in which we are mired.

Archbishop Alexander Sample’s “The Bishop: Governor, Promoter, and Guardian of the Liturgical Life of the Diocese” (pp. 255–71) created a stir at the conference for its comprehensiveness and clarity, bringing into one place all the most important conciliar and post-conciliar magisterial teachings on the precise role and responsibility of the bishop over the liturgy in his diocese—what he is obliged to do and what he should not do. His Excellency then makes a point of addressing Summorum Pontificum and its implications for the ministry of the bishop:

I would urge bishops to familiarize themselves with the usus antiquior as a means of achieving their own deeper formation in the liturgy and as a reliable reference point in bringing about renewal and reform of the liturgy in the local Church. Speaking from personal experience, my own study and celebration of the older liturgical rites has had a tremendous effect on my own appreciation of our liturgical tradition and has enhanced my own understanding and celebration of the new rites.Complementary to this talk is Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke’s far-reaching, authoritative, and typically thorough “Liturgical Law in the Mission of the Church” (pp. 389–415), which refutes postconciliar antinomianism, establishes the right of God to receive due worship, and demonstrates how canon law supports this right and duty. It is worth mentioning, as a heartening "sign of the times," that among the 23 contributors to this volume are 4 cardinals, 4 bishops, 2 ordinaries, and 2 abbots. We are, thanks be to God, well past those dark days when the liturgical movement had nearly no hierarchical support or public profile.

I would further encourage bishops to be as generous as possible with the faithful who desire and ask for the opportunity to worship in the usus antiquior in their dioceses. Allowing for its natural flourishing will have its own effect on the liturgical life of the whole diocesan Church. It must never be seen as something out of the mainstream of ecclesial life, that is, as something on the fringes. The bishop’s own public celebration of it can prevent this from happening. (p. 270)

For me personally, the talk that hit me in the gut and left me speechless was Msgr. Ignacio Barreiro Carámbula’s “Sacred Liturgy and the Defense of Human Life” (pp. 371–88). With incomparable candor, detail, and theological acumen, Msgr. Barreiro exposes the relationship between the ravaging of liturgical tradition and the destruction of the family, and how the lack of reverence towards God, especially as present in the mystery of the Mass and the Most Holy Eucharist, has trickled down into contempt for the unborn. His address held no less power for me when I re-read it in the book. An excerpt:

Recently Bishop Athanasius Schneider reminded us that the worst sin that humanity can commit is to refuse to adore God, to refuse to give Him the first place, the place of honor. A man that does not adore God in the liturgy will not value the main gift of God, which is life. A secularized man that considers himself autonomous will be uncomfortable that the tabernacle would be at the center of the Church or that the cross should be at the center of the altar.The contributions from Fr. Nicola Bux, Fr. Andrew Burnham, Fr. Guido Rodheudt, and Fr. Paul Gunter are also noteworthy, but having said that, I want to reiterate that, surprisingly, there is no weak link in this lengthy chain: all 21 papers in this book are worth reading and re-reading carefully. Indeed, I predict that whoever gets this book and dips into it will either start photocopying pages from it for his friends (and perhaps also his enemies), or will buy more copies and give them away as gifts. Our profound gratitude is owed to all the conference speakers who, by means of this superb collection, now share their work with a worldwide audience.

Secularization rejects the right relation of man with God. Secularization denies our dependence from God, so it refutes Him as giver of life and that man by his nature is a being that adores, giving due worship to God. We are all sensitive to the justice that is due to our neighbor, but the precedence should be given to the justice that is due to God. Catholicism has to be understood as a society of men who give to God the right worship and as a consequence they provide service to their fellow men. Service [to the neighbor] should not have priority, instead service should be the consequence of worship. In some ways we can say that service is a continuation that flows from worship. (p. 372)

In conclusion, I am willing to say, without the slightest hyperbole, that this book can serve as a kind of charter for the new liturgical movement—and I hope it shall do so.

↧

Via Juventutem DC

Gregory has already posted below about the Solemn Requiem Mass for the slain Fr. Kenneth Walker, to be broadcast on LiveMass.net, in a little over an hour today (6:30 PM Fribourg time, 12:30 PM Eastern), but I thought I would post a reminder in the form of this graphic from our friends at Juventutem DC. Requiem aeterna dona ei, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei, cum sanctis tuis in aeternum. ![]()

↧

↧

Dom Alcuin Reid to Speak at St. Mary Church, Norwalk, CT

Following upon this morning's post of a review of The Sacred Liturgy, Source and Summit of the Life and Mission of the Church, I'm delighted to announce a talk by Dom Alcuin Reid to be given this Friday, June 20th at 7:30 p.m. at the Church of St. Mary in Norwalk, Connecticut. All are cordially invited to attend.

![]()

↧

Living Latin Program at Belmont Abbey College

The second annual Veterum Sapientia Latin conference is being hosted at Belmont Abbey College outside Charlotte, NC this July 27-August 2.

The program is for priests, seminarians, and religious (male and female).

The program is named after the Apostolic Constitution Saint John XXIII signed on the high altar of St. Peter's defending and promoting the study of Latin by seminarians.

The instructors are Msgr. Dan Gallagher of the Vatican Latin office, Dr. Nancy Llewellyn of Wyoming Catholic College, Dr. John Pepino of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary (FSSP), and Dr. Gerald Malsbary of Belmont Abbey College.

The program is intended for intermediate to advanced students of Latin, the minimum being two semesters of seminary Latin. It will be conducted entirely in Latin (or almost, depending on the skill level of participants). Through activities, conversation, and games the full-immersion experience helps reading comprehension and one's overall command of the language.

Cost is $250. Boarding is $25/night for a BAC dorm room. More information is available by clicking here.![]()

The program is for priests, seminarians, and religious (male and female).

The program is named after the Apostolic Constitution Saint John XXIII signed on the high altar of St. Peter's defending and promoting the study of Latin by seminarians.

The instructors are Msgr. Dan Gallagher of the Vatican Latin office, Dr. Nancy Llewellyn of Wyoming Catholic College, Dr. John Pepino of Our Lady of Guadalupe Seminary (FSSP), and Dr. Gerald Malsbary of Belmont Abbey College.

The program is intended for intermediate to advanced students of Latin, the minimum being two semesters of seminary Latin. It will be conducted entirely in Latin (or almost, depending on the skill level of participants). Through activities, conversation, and games the full-immersion experience helps reading comprehension and one's overall command of the language.

Cost is $250. Boarding is $25/night for a BAC dorm room. More information is available by clicking here.

↧

Should There Be A Frame on Sacred Art? What Should it Look Like?

or doesn't it matter?

When I recently did a painting of a seascape to hang on the wall of the office of lawyer Ray Tittman (founding partner of the California office of law firm Edison, McDowell & Hetherington LLP). He wanted something that was consistent with the Faith, and would bear witness without being too obvious - appropriate to a lawyer's office in a modern block in downtown Oakland. I suggested a slightly abstracted landscape that would reflect the beauty of God's Creation and through harmonizing with the color scheme of the office, could set a mood for an office and then in a discrete way put a small Holy Image on the wall in his personal space behind the desk that was nevertheless clearly visible to his clients. In fact he asked for a seascape and it was delivered earlier this year. I was asked by some who saw it about the red border on the painting (as you can see below and above, left). Why did I do this they asked, is it just for aesthetic reasons?

The answer in fact is no. I thought about it very carefully, and here is my thinking. I did consider the aesthetics of course, but I think also that as a general principle, a frame and or a border are necessary parts of a painting. One the one hand, this was a modern office and in the other offices and main foyer there were modern abstract paintings. To be in harmony with these, I wanted to accommodate the modern style of edging (the cream yellow strip that runs down the side of the canvas) so that it would harmonize with the other paintings. An ornate gilded baroque frame would not have looked right here, but I wanted something more noticeable than just a thin wooden edge. After thinking about it, I deliberately added a red border around the painting, which is just painted in oil paint like the rest of it. I got this idea from my experience of painting icons and gothic style images, where often the border is painted into the image itself.

If you go around any museum of modern art you will see oil paintings hanging on the wall without any obvious frame at all. If there is anything visible you will see that thin wooden strip around the edge. This strip is applied more to hide the nails or staples that are used to fix the canvas to the wooden stretcher bars and is deliberately painted and fixed in such a way that it isn't very noticeable.

It might be that even the modern curator would choose this style of frame for positive reasons - ie not just to hide nails - because he likes the neatness of the edging perhaps. However, I doubt that any would assert that a painting ought to be visibly framed for theological reasons, as I would. As I will explain below, in my view, this lack of interest in a framing is consistent with the modern atheist/materialist worldview; as a Christian I chose to adapt the modern method and deliberately painted a border and made the edge and the border in contrasting but complimentary colors so that both would be seen very clearly.

Here are my reasons:

When I went to icon painting classes from Orthodox teachers, I was always asked to put a border around the image of the icon I was studying. I was told that this served the purpose of mediating between the image, which portrays the heavenly dimension and the natural world. The border in this case was a flat painted or gilded region raised slightly from the plane of the image. If the composition allowed for it, we designed the icon so that a figure encroached slightly into the boundary region, perhaps the sleeve, a foot or the halo. Aidan Hart, my teacher, told me that this encroachment communicates the idea that nothing can contain God.

Looking generally, at images painted in the iconographic tradition the principle of the boundary represented in some form appears to be the norm. Going around the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Massachusetts, for example, all had a boundary painted on and most, but not all, had a raised boundary. These were all wooden panel icons. Iconographic images in other media, such as mosaic, fresco and illuminated manuscript will, from what I have observed, generally have a painted border, but the image and frame are in the same plane.

In Western iconographic imagery, such as Celtic, Ottonian or Romanesque art, the border is painted as an ornate abstract pattern, often geometric in form. This is consistent with the previously stated idea of the border or frame mediating between the image and reality. The world of geometry, like that of mathematics, is an idealized domain that sits between the natural and the supernatural. We can think of the ideal shape of a triangle in the abstract, separated from all matter; but at the same time this ideal it can be applied, albeit imperfectly, to matter and we can construct, for example, wooden triangles. Also, the world of geometry and mathematics also obeys the rules of logic that govern the natural and the supernatural realms. This intermediary status makes patterned, geometric or mathematical art perfect for the adornment of a border. The image below is from an ancient Irish manuscript of about the 8th century.

It has occurred to me that there is a practical reason for having a raised border on wooden panel icons. Unlike frescos and mosaics, they are portable and are meant to be handled, kissed and raised in procession. It is inevitable that they will get chipped and damaged in the rough and tumble of devotional prayer! Raising the border, will help to ensure that it gets damaged rather than the image it frames – just like the idea behind the fender on a car. Aidan Hart, my teacher, always used to joke that an icon hasn’t been serving its purpose if it isn’t bashed about a bit.

So what about the other liturgical traditions of the Church, the gothic and the baroque? They do not portray the heavenly realm in the same way – is there need for a frame there too? The answer is yes. Here is a close-up of a baroque frame.

In consideration of this we need to state that a baroque or a gothic painting are both traditions that portray Holy Icons, in the broader sense of the term in which ‘icon’ means ‘image’. This is the sense of the word 'icon' used by the 7th Ecumenical Council and the great Father of the Church who opposed the iconoclasts, Theodore the Studite. Theodore made it plain that an image is distinct from the person depicted – that is, the essence of the person is absolutely not present in an icon. There is, however, a profound relationship established with the saint depicted when we look at an image because the icon directs the imagination of the person who regards the image to the real saint in heaven. The icon does this by virtue of the distinctive characteristics of the saint captured in the image; and the writing of the name of the saint on it. In this way it facilitates the action of grace in the way that a sacramental does.

Thinking now about how this applies to the other liturgical art forms: the starting point may be different in each case, but what all three traditions have in common is their goal, the contemplation of heavenly things. To illustrate this point: we can say that ‘iconographic’ tradition, which we have been referring to so far, portrays Eschatological Man; the baroque portrays Historical Man, that is fallen man; and the gothic portrays the transition between the two by degrees – it is the art of pilgrimage. So in the dynamic of prayer Eschatological (‘iconographic’) art, takes directly to heaven, it starts and finishes there, as it were. The baroque on the other hand starts in a fallen world, but from there directs our thoughts to heaven.

Given this common aspect of direct our attention to heaven, any argument about a frame or border that applies to iconographic art, applies as much to the gothic or the baroque. And when we look at the gothic and the baroque, it is no surprise that they are always framed. These borders are not always the hard-edged geometric patterns, but can also be shapes evoking a sense of idealized, ordered vegetation incorporating gracefully flowing lines. All three traditions seem happy to use either form of pattern, or none at all in their borders. However, if there is a trend, one could say that that the baroque frame is most easily identified with idealized form of vegetation. The form is most commonly referred to as a ‘baroque scroll’ portrays, often ornately carved and gilded rather than painted, wonderful flowing lines of leaves and branches, especially incorporating the shallow ‘S’. This is in keeping with the baroque basis of idealization, which focuses on the portrayal of the fallen nature from a heavenly vantage point, and has a more subtle idealization and hence is closer to natural appearances than its sister traditions.

So what about the mundane? Should traditional landscapes or portraits be framed too? The answer is yes, in my opinion. Baroque art is not just sacred imagery. There portraits and landscapes too, which were not intended to be simply naturalistic representations. Reflecting an authentic Christian humanism, the artists sought to reveal the Creator in the beauty of his Creation, and in doing so used the same visual vocabulary of sacred art, namely the variation focus, muted colour and contrast between light and dark that was developed first for baroque liturgical art.

So what about the mundane? Should traditional landscapes or portraits be framed too? The answer is yes, in my opinion. Baroque art is not just sacred imagery. There portraits and landscapes too, which were not intended to be simply naturalistic representations. Reflecting an authentic Christian humanism, the artists sought to reveal the Creator in the beauty of his Creation, and in doing so used the same visual vocabulary of sacred art, namely the variation focus, muted colour and contrast between light and dark that was developed first for baroque liturgical art.

Whether intentional or not, this principle seems to apply in modern art too to some degree. In the secular, atheist materialist world view there is no recognition of the supernatural. There is no need to mediate between the natural and the supernatural if you don’t believe the supernatural exists. Perhaps this is why museums don’t see the need to frame these works. On the other hand it might be just as much a reflection of the general trend of a casual approach in presentation – just as men no longer wear a tie for the opera, the theatre or for church…but this is a different debate.

Mark Rothko, 20th century

↧

Revised Tomb Design for Richard III Revealed

A previous design for the tomb was unveiled in November but put on hold amid the legal challenges the reburial has faced. The original plans called for a budget of £1.3 million. The original design was to be carved in Swaledale fossil limestone and laid upon a large inlaid pavement in the shape of a rose surrounded by a black band in which the king's motto Loyaulte me lie would be inscribed. Only £96,000 of the original total estimated budget was actually slated for the vault and tomb; the project also includes a relocated crossing-altar and wooden parclose screens; it appears the low-laying tomb will actually be occupying the cathedral's old chancel. A new garden area outdoors seems to be part of the budget as well. An even earlier plan recommended a simple flat slab incised with a cross, but this proved so disappointing that several backers withdrew their support. The revised design retains the core element of the composition, a skewed, vaguely Brutalist block of marble incised with a cross. It dispenses with the oversized, rather kitschy inlaid rose on the floor (described by one cathedral official as "not universally liked") for a quieter step of black stone inlaid with the royal arms in full color. Despite this simplification, the budget has now risen to £2.5 million.

In some respects, there is nothing truly wrong about the design, but there is very little right, either. The black marble plinth and the royal arms are rather dignified additions and an improvement on the rose pavement. Overall, however, it is a great disappointment. It is possessed of a postmodern timidity and museum-like detachment. Yoking the project to an au courant liturgical re-ordering complete with an undersized, exposed freestanding altar was already problematic, but the proposed tomb itself is at odds both with the fabric of the church and the medieval world which Richard III was in some respects the last royal exemplar. It resembles a diagram of a contemporary idea of what a medieval tomb ought to look like, at about ten removes from reality, done as a sort of dead design exercise, rather than an attempt to grapple with the organic realities of the Gothic. They have turned Richard III, a man who, whether or not Shakespeare was accurate, could never be called dull, unto something tasteful, quiet, and timid. Turning the former chancel into a potentially high-traffic tourist area also opens up all sorts of other troubling liturgical implications.

Given that the latest and greatest exemplar of British Gothic revival, Stephen Dykes-Bower, was practicing up to his death in 1994, in a style both characterized by a vigorous imagination and a careful understanding of the sources, and his work was completed with the stupendous new Gothic crossing-tower built at St. Edmundsbury by Warwick Pethers within the last decade, that the public should have this mute slab foisted upon it, and upon the memory of a complex and perhaps misunderstood monarch, is inexplicable, and shows both a lack of artistic courage and historical imagination.

Instead, I applaud the historian who has commissioned a splendidly medieval funeral crown for the body, as well as the gentlemen of the Richard III Society who unveiled a somewhat restrained but handsome and historically-informed concept for the tomb themselves early last year. The past is not dead; it's not even past. What is needed here is not postmodern timidity or even archaeological exactitude but the ability to think, breathe, and yes, pray, like a medieval man, and translate that passion, beauty and life into funereal cold stone. It is a pity that nobody in England appears up to the task.

↧

↧

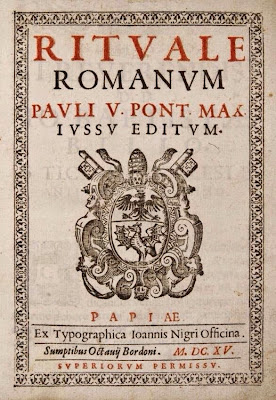

The Fourth Centenary of the Rituale Romanum of Pope Paul V : June 17, 1614

With the bull Apostolicæ sedi of June 17, 1614, Pope Paul V Borghese promulgated the Rituale Romanum (Roman Ritual) four centuries ago. The Rituale is the penultimate liturgical book of the Tridentine Reform; in chronological order they are: the Roman Breviary of 1568; the Roman Missal of 1570; the Roman Martyrology of 1584; the Roman Pontifical of 1595; the Ceremonial of Bishops of 1600; the Monastic Breviary of 1612; the Roman Ritual of 1614; and the Octavarium of 1628.

The origins of the Rituale

The Roman Ritual contains the ceremonies – apart from those of the Mass and Divine Office – which a priest may need to perform, such the administration of the Sacraments (Baptism, Marriage, Anointing of the Sick, Communion for the sick), funerals, and blessings.

In the early centuries, the prayers for these functions are found most often in the Sacramentaries, which however did not describe the details of the ceremonies or give the relevant chants. When the Sacramentaries disappeared in the Middle Ages, to be replaced by Missals (which, in addition to the prayers of the Sacramentaries, contain the chants and readings of each Mass), there slowly developed as a parallel to the Missal a more-or-less complete manual to help priests perform the ceremonies apart from of the Mass which they might be called upon to celebrate.

During the Middle Ages, this type of book multiplied widely. They existed a version for every diocese, or even for individual religious communities, with a great variety of names. So, for example, the diocese of Paris printed a Manuale Sacerdotum (Priests’ Manual) during the episcopacy of Jean Simon de Champigny in 1497.

The immediate predecessors of the Rituale of 1614

During the 16th century, certain Roman liturgists published three editions with the authority of the Pope himself.

The 1523 Sacerdotale of Castellani

Published at Venice by the Dominican liturgist Alberto Castellani in 1523, this work was approved by Pope Leo X. The Roman character of the book is proclaimed by its title, “Sacerdotale juxta usum Sanctæ Romanæ Ecclesiæ”. (Priestly book according to the use of the Holy Roman Church) Castellani divided his material into three parts: Sacraments, blessings and processions; this will become the standard organization in subsequent Rituals.

The 1579 Sacerdotale of Samarini

This is a Roman edition based on the preceding work of Castellani, titled “Sacerdotale sive sacerdotum Thesaurus collectus.”

The 1602 Rituale of Santorius

This was published at Rome in 1602 with the title Rituale Sacramentorum Romanum. In 1584, Pope Gregory XIII, the successor of St. Pius V, had commissioned Cardinal Santori to prepare a Ritual more in keeping with the requests of the Council of Trent, especially in regard to the administration of the Sacraments. After the Pope’s death the following year, Santori continued his work with the blessing of Sixtus V and of Clement VIII. In 1602, Cardinal Santori died, and his heirs then published his work.

The Rituale Romanum of 1614

However, Pope Paul V (1605-1621) did not approve the works published by the heirs of Cardinal Santori as such, and preferred to publish another Rituale in 1614, while using many of the elements already present in Santori’s.

In the constitution Apostolicæ sedi of June 17, 1614, Pope Paul V notes that Clement VIII had published two official books for bishops, the Pontifical of 1595 and the Ceremonial of 1600. He also notes that these works establish the normal form of some liturgical functions which can also be celebrated by a simple priest, and that therefore, a book for priests is also needed in harmony with the other liturgical books published for use in Rome. (click here to download the Rituale Romanum of Paul V)

The Ritual of Paul V adopts the organization of the material already present in the Sacerdotale of 1523: Sacraments, blessings, processions, in that order. It also adds, as we will see, a fourth part.

The book presents first of all the administration of the Sacraments: Baptism, Confession, the Eucharist (and especially Viaticum), Extreme Unction. The seven Penitential Psalms and the Litany of the Saints – connected to Confession – form a link with the visitation of the sick, the Commendation of the Dying, funerals, the Office of the Dead, and the funeral of young children. The various sung parts of the funeral service and the Office of the Dead are noted in plain chant.

After this digression, which goes from the treatment of the illness of the soul to that of the body, and from there to death, the Ritual ends the course of the sacramental life in a fairly droll, (not to say surprising) way, with marriage.

There follows the part dedicated to blessings, beginning with the blessing of holy water before the principle Mass on Sunday. Among these are also certain blessings reserved to bishops which were not included in the Pontifical. Where chant pieces appear, they are printed out with the full notation.

A third part is dedicated to the processions of Candlemass, Palm Sunday, the Major and Minor Litanies, and Corpus Christi, followed by those for special occasions, such as bad weather, wartime, a procession for thanksgiving, for the translation of relics, etc. The chants for these processions are also given.

The book adds a fourth part containing various exorcisms, and ends with the formulas to be used when filling out a parish register.

Impact of the Rituale of 1614

Paul V did not make his work obligatory, nor did he abolish other similar works in use at the time, or order anyone to use his. He simply published a model, from which diocesan editions might draw their inspiration.

There continued to be many of the latter. Speaking only of France, in 1984 Jean-Baptiste Molin and Annick Aussedat-Minvielle counted no less than 2952 editions of various Rituals and Processionals. However, with the abandonment of the particular rites of dioceses over the course of the 19th century, and the adoption of the Roman Missal, the diocesans editions of the Rituals gradually passed out of use (the last in France seems to date to 1853) and the Roman Ritual was adopted everywhere.

Additions to the Ritual of 1614

Because he wished to provide a work that would serve as a model for others, Paul V promulgated a fairly simple text, containing that which had long been standard practice more or less everywhere in the West. This rather minimal text left something to be desired.

In the 17th century, we note here and there various printings of small supplements which are presented as if they if they were derived from the work of Paul V. I make particular note of the ancient ceremony for the solemn blessing of water on the vigil of the Epiphany, added to the Rituale Romanum in 19th century, an improvement made at the cost of a grave very badly executed mutilation of this venerable ceremony.

Numerous new editions of the Ritual of 1614 were published, introducing changes of various sorts, generally enriching the part dedicated to blessings, and organizing the material better and with different titles. These were issued by Popes Benedict XIV in 1742, Bl. Pius IX in 1862), Leo XIII in 1884, Pius XI in 1925, and Pius XII in 1952.

Despite the various editions, the text which has come down to us remains essentially the same, and the use of it remains authorized and protected by the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum of July 7, 2007, as we celebrate the 400th anniversary of its promulgation.

(This article originally appeared in French on the blog of the Schola Sainte Cécile)

The origins of the Rituale

The Roman Ritual contains the ceremonies – apart from those of the Mass and Divine Office – which a priest may need to perform, such the administration of the Sacraments (Baptism, Marriage, Anointing of the Sick, Communion for the sick), funerals, and blessings.

In the early centuries, the prayers for these functions are found most often in the Sacramentaries, which however did not describe the details of the ceremonies or give the relevant chants. When the Sacramentaries disappeared in the Middle Ages, to be replaced by Missals (which, in addition to the prayers of the Sacramentaries, contain the chants and readings of each Mass), there slowly developed as a parallel to the Missal a more-or-less complete manual to help priests perform the ceremonies apart from of the Mass which they might be called upon to celebrate.

During the Middle Ages, this type of book multiplied widely. They existed a version for every diocese, or even for individual religious communities, with a great variety of names. So, for example, the diocese of Paris printed a Manuale Sacerdotum (Priests’ Manual) during the episcopacy of Jean Simon de Champigny in 1497.

The immediate predecessors of the Rituale of 1614

During the 16th century, certain Roman liturgists published three editions with the authority of the Pope himself.

The 1523 Sacerdotale of Castellani

Published at Venice by the Dominican liturgist Alberto Castellani in 1523, this work was approved by Pope Leo X. The Roman character of the book is proclaimed by its title, “Sacerdotale juxta usum Sanctæ Romanæ Ecclesiæ”. (Priestly book according to the use of the Holy Roman Church) Castellani divided his material into three parts: Sacraments, blessings and processions; this will become the standard organization in subsequent Rituals.

The 1579 Sacerdotale of Samarini

This is a Roman edition based on the preceding work of Castellani, titled “Sacerdotale sive sacerdotum Thesaurus collectus.”

The 1602 Rituale of Santorius

This was published at Rome in 1602 with the title Rituale Sacramentorum Romanum. In 1584, Pope Gregory XIII, the successor of St. Pius V, had commissioned Cardinal Santori to prepare a Ritual more in keeping with the requests of the Council of Trent, especially in regard to the administration of the Sacraments. After the Pope’s death the following year, Santori continued his work with the blessing of Sixtus V and of Clement VIII. In 1602, Cardinal Santori died, and his heirs then published his work.

The Rituale Romanum of 1614

However, Pope Paul V (1605-1621) did not approve the works published by the heirs of Cardinal Santori as such, and preferred to publish another Rituale in 1614, while using many of the elements already present in Santori’s.

In the constitution Apostolicæ sedi of June 17, 1614, Pope Paul V notes that Clement VIII had published two official books for bishops, the Pontifical of 1595 and the Ceremonial of 1600. He also notes that these works establish the normal form of some liturgical functions which can also be celebrated by a simple priest, and that therefore, a book for priests is also needed in harmony with the other liturgical books published for use in Rome. (click here to download the Rituale Romanum of Paul V)

The Ritual of Paul V adopts the organization of the material already present in the Sacerdotale of 1523: Sacraments, blessings, processions, in that order. It also adds, as we will see, a fourth part.

The book presents first of all the administration of the Sacraments: Baptism, Confession, the Eucharist (and especially Viaticum), Extreme Unction. The seven Penitential Psalms and the Litany of the Saints – connected to Confession – form a link with the visitation of the sick, the Commendation of the Dying, funerals, the Office of the Dead, and the funeral of young children. The various sung parts of the funeral service and the Office of the Dead are noted in plain chant.

After this digression, which goes from the treatment of the illness of the soul to that of the body, and from there to death, the Ritual ends the course of the sacramental life in a fairly droll, (not to say surprising) way, with marriage.

There follows the part dedicated to blessings, beginning with the blessing of holy water before the principle Mass on Sunday. Among these are also certain blessings reserved to bishops which were not included in the Pontifical. Where chant pieces appear, they are printed out with the full notation.

A third part is dedicated to the processions of Candlemass, Palm Sunday, the Major and Minor Litanies, and Corpus Christi, followed by those for special occasions, such as bad weather, wartime, a procession for thanksgiving, for the translation of relics, etc. The chants for these processions are also given.

The book adds a fourth part containing various exorcisms, and ends with the formulas to be used when filling out a parish register.

Impact of the Rituale of 1614

Paul V did not make his work obligatory, nor did he abolish other similar works in use at the time, or order anyone to use his. He simply published a model, from which diocesan editions might draw their inspiration.

There continued to be many of the latter. Speaking only of France, in 1984 Jean-Baptiste Molin and Annick Aussedat-Minvielle counted no less than 2952 editions of various Rituals and Processionals. However, with the abandonment of the particular rites of dioceses over the course of the 19th century, and the adoption of the Roman Missal, the diocesans editions of the Rituals gradually passed out of use (the last in France seems to date to 1853) and the Roman Ritual was adopted everywhere.

Additions to the Ritual of 1614

Because he wished to provide a work that would serve as a model for others, Paul V promulgated a fairly simple text, containing that which had long been standard practice more or less everywhere in the West. This rather minimal text left something to be desired.

In the 17th century, we note here and there various printings of small supplements which are presented as if they if they were derived from the work of Paul V. I make particular note of the ancient ceremony for the solemn blessing of water on the vigil of the Epiphany, added to the Rituale Romanum in 19th century, an improvement made at the cost of a grave very badly executed mutilation of this venerable ceremony.

Numerous new editions of the Ritual of 1614 were published, introducing changes of various sorts, generally enriching the part dedicated to blessings, and organizing the material better and with different titles. These were issued by Popes Benedict XIV in 1742, Bl. Pius IX in 1862), Leo XIII in 1884, Pius XI in 1925, and Pius XII in 1952.

Despite the various editions, the text which has come down to us remains essentially the same, and the use of it remains authorized and protected by the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum of July 7, 2007, as we celebrate the 400th anniversary of its promulgation.

(This article originally appeared in French on the blog of the Schola Sainte Cécile)

↧

Ecce Panis Angelorum

From the Solemn Mass with the St. Cecilia choir to the glorious outdoor procession with the Blessed Sacrament in the parish gardens, the feast of Corpus Christi at St. John Cantius Church in Chicago is an important experience for parishioners and visitors. Flowers and incense prepare the way for the Blessed Sacrament, and elaborate chalk designs adorn the pathways to the various altars set up for the procession. The times of the two biggest Masses are listed below.

From the Solemn Mass with the St. Cecilia choir to the glorious outdoor procession with the Blessed Sacrament in the parish gardens, the feast of Corpus Christi at St. John Cantius Church in Chicago is an important experience for parishioners and visitors. Flowers and incense prepare the way for the Blessed Sacrament, and elaborate chalk designs adorn the pathways to the various altars set up for the procession. The times of the two biggest Masses are listed below.Wednesday, June 18 - 7:30pm

Anticipated Feast of Corpus Christi (1962)

7:30 pm - Solemn High Latin Mass and indoor procession

Music sung by Cantate Domino Choir

Missa Brevis, Claudio Casciolini

Propers of Corpus Christi, Giuseppe Tartini

Salve Regina, Op. 171,No. 3, Josef Gabriel Rheinbe

Sunday, June 22, 11:00am

External Observance of Corpus Christi (1962)

Solemn High Tridentine Mass and Outdoor Procession

Missa Octava, Hans Leo Hassler (1564 – 1612)

Sequence: Lauda Sion, Roland Lassus (1532 – 1594)

Venite Ad Me, Felice Anerio (1560 – 1614)

O Sacrum Convivium, Cristòbal de Morales (1500 – 1553)

The photographs below are taken from past Corpus Christi processions at St John Cantius. It's worth remembering the inspiring words of the Pastor, Father Frank Phillips, who said "any parish can do what we are doing here". More information from the St John Cantius website here. Please add details of your own Corpus Christi Processions in the comments below.

↧

Canons Regular of the New Jerusalem 12th Anniversary Mass

↧

Photos of the Recent FSSP Ordinations in Virgina

Our thanks to Mr. Craig Spiering of Spiering Photography for his kind permission to share with our readers some of his photographs from the FSSP Ordination recently held this past Saturday at the Church of St. John the Apostle in Leesburg, Virginia. The complete set of images can been seen by clicking here.

NLM is very pleased to offer congratulations to the newly ordained priests, Fr. Zachery Akers and Fr Daniel Heenan, to their families, and to the entire Fraternity of St. Peter, as well as our thanks to the ordaining bishop, His Excellency James Conley of Lincoln, Nebraska, and to Bishop Paul Loverde of Arlington, Virginia. Ad multos annos!

NLM is very pleased to offer congratulations to the newly ordained priests, Fr. Zachery Akers and Fr Daniel Heenan, to their families, and to the entire Fraternity of St. Peter, as well as our thanks to the ordaining bishop, His Excellency James Conley of Lincoln, Nebraska, and to Bishop Paul Loverde of Arlington, Virginia. Ad multos annos!

↧

↧

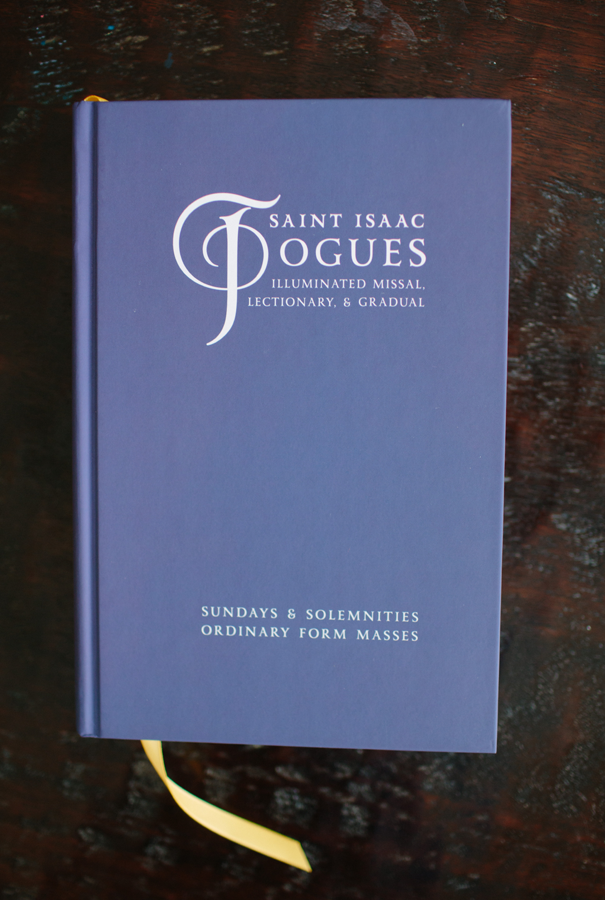

Book Review: Saint Isaac Jogues Illuminated Missal, Lectionary, and Gradual

Saint Isaac Jogues Illuminated Missal, Lectionary, and Gradual. 818 pages, hardcover, with full color section. Owasso, OK: Pope John Paul II Institute for Liturgical Renewal, 2014. $22.99 (single copy); bulk discounts from $21.99 to $13.99.

We are living in the midst of a veritable renaissance of beautiful new resources for celebrating the liturgy of the Roman Rite in both forms. It is as if, at last, the best of our tradition and the best prescriptions of Sacrosanctum Concilium are coming together for the benefit of the faithful. There is a kind of momentum building for the hermeneutic of continuity. Where just a few years ago it was hard to find the Propers of the Mass in vernacular plainchant, today there is a plethora of options, along with many fine articles explaining the whys and wherefores; where publications for the old rite were out of print and/or outrageously expensive, today there are reprints and new editions pouring forth from the presses.

The new liturgical movement is finding its singing voice and its material means for long-term growth and expansion. In this sense, although the Reform of the Reform faces enormous difficulties and the resurgence of the traditional Latin Mass has an uphill climb, there is also the hope of real progress after 40 years of the People of God wandering in the desert. Pastors and chaplains, musicians and music directors, DREs, everyone involved with the liturgical life of the Church, finally have fantastic products to choose from that can guide and sustain their pastoral programs for years to come. An example for the Ordinary Form would be the Lumen Christi Simple Gradual, reviewed here by NLM's David Clayton; an example for the Extraordinary Form would be the Saint Edmund Campion Missal & Hymnal, which I reviewed here.

It is to another project associated with Corpus Christi Watershed that I now turn my attention: the recently released Saint Isaac Jogues Illuminated Missal, Lectionary, and Gradual. (I should note that while Jeffrey Ostrowski was chief editor of this book and promotes it via the CCW website, it is the fruit of a group called the Pope John Paul II Institute for Liturgical Renewal.) There is a lot to say about this multi-layered book, a true labor of love and a work of beauty from start to finish. I could sum up my reaction by saying that the Jogues Missal does for the Ordinary Form what the Campion Missal does for the Extraordinary Form.

As its full title indicates, the Jogues Missal brings together the rich texts of the Roman Gradual (i.e., the Introit, Gradual, Alleluia or Tract, Offertory, and Communion antiphons) and the readings of the Lectionary (including responsorial psalms and Gospel acclamations) and places in their midst a magnificent full-color Order of Mass (pp. 251-314). Like the Campion Missal, the Jogues Missal is for Sundays and Solemnities of the Church year. Unlike the Campion, which includes a substantial hymn section, the Jogues is simply for following along with the texts and ceremonies of the liturgy; a planned companion volume, the Saint Isaac Jogues Hymnal, will be a dedicated music resource with hundreds of hymns, but there is no particular reason that the Jogues Missal could not be paired with other musical resources such as the Lumen Christi Simple Gradual. (The Jogues Missal does include a modest amount of music: Chabanel Psalm setting for each Mass; Sequences in metrical English versions with simple tunes, with the original Latin texts and literal translations in an appendix; a couple of hymns for Benediction; and the Mass in Honor of St. Isaac Jogues, a plainchant setting that includes the Creed.)

When I first opened the package, I was blown away by the aesthetic qualities of the Jogues Missal. The elegance of the page layout is perhaps what strikes the eye first: graceful drop caps of hierarchically gradated size and design are used for various propers and readings, drawing the eye gently to their place in the liturgy; decorative borders set apart the different days; exquisite full-page black and white etchings for major feastdays, surrounded by Scripture verses, plunge us into the mysteries of God and the saints. These qualities render the book a truly worthy instrument for deeper interior participation in the sacred liturgy.

The Order of Mass section is the most striking feature of the Jogues Missal. I have access to a very large collection of liturgical books, and I regret to say that practically none of them manages to convey any conscious or subconscious impression that the Ordinary Form can be a beautiful thing. We have been plagued by utilitarianism and pragmatism for decades, and it often seems as if the traditional Latin Mass is the only surviving refuge for a heightened sensitivity to beauty in every last detail. What the Jogues Missal accomplishes in this regard is nothing short of astonishing. The photos call to mind the historic heritage of the Roman Rite: the glory of its musical heritage; the pregnant symbolism of the different parts and actions of the Mass, with a loving attention to details of ritual; the fittingness of suitable architecture and vesture; even the sacredness of particular words. There is a kind of programmatic “re-enchantment” of the missal that takes place in these pages, simply by the force of loving what the Church herself offers and not filtering it through a reductionistic Bauhaus lens.

This brings me to an interesting angle: the Jogues Missal as an instrument of liturgical renewal and reform. It is no secret that the way the OF Mass is celebrated in most communities bears little likeness to the images represented in this missal's pages. The celebrating priest is displayed wearing a maniple (e.g., p. 263 and p. 277) which matches his ornate red and white chasuble; the altar server is in cassock and surplice, and even the men’s schola is similarly attired (p. 273). One lady is wearing a mantilla (p. 265). Mass is being celebrating ad orientem towards a Gothic high altar with six lit candles and a statue of Our Lady (e.g., p. 266, p. 300); naturally, incense is featured (p. 276). The chalice is gloriously ornate gold and silver (e.g., p. 292). The priest holds his thumb and forefinger together after consecration (p. 300). Holy communion is distributed on the tongue to those who are kneeling (p. 310). And throughout, the assumption is that the Propers are being chanted, whether in the vernacular or in Latin (the second color image, on p. 252, is of a Gregorian chant manuscript with an Introit). Indeed, the very first color image (p. 251; see below) is a Crucifixion-Trinity scene surrounded by the nine orders of angels, with a priest at the bottom raising the chalice ad orientem: a paradigm of the entire approach here, which could be described as “ROTR to the Max.”

All this makes the Jogues Missal an ideal tool for pastors who are seeking to move their community towards a more elevated, solemn, beautiful, and traditional celebration of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite or who, already blessed to be at that point, wish to consolidate the good they have. The book itself seems to anticipate such a purpose: along with the Order of Mass, printed in large readable type, one finds small blocks of commentary in fine print explaining aspects of the Mass and its ceremonial. To some this might appear overly didactic, but my impression is that it is tastefully done and appropriate, especially in an age when liturgical formation is desperately needed. It could certainly be a marvelous tool for liturgical catechesis, whether in preaching or during RCIA and other religious education programs.

Best of all, the Jogues Missal carries on the copyright page the following notice: “Published with the approval of the Committee on Divine Worship, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 20 March 2014,” followed by the Imprimatur of Most Reverend Edward J. Slattery, Bishop of Tulsa. No one can point to these features—the ad orientem worship, the use of the maniple, the wearing of the mantilla, kneeling for communion, etc.—and say: “This is not to be done in the Ordinary Form.” Those of us who have studied the relevant documents know that they are permissible, but does the average Catholic? And should one have to be a scholar in order to defend traditional practices or common sense views? The Jogues Missal provides a key piece that was missing in the English-speaking world until now: a “This, folks, is really how it’s done” pew resource that unashamedly embraces the ROTR model of Benedict XVI.

The Ordinary Form of the Mass is going to be around for a very long time, regardless of what we may think about its strengths and weaknesses, and it would be hard to dispute that it should be offered as beautifully and solemnly as can be done, ad majorem Dei gloriam. As a matter of fact, proponents of the traditional Latin Mass (like myself) would do well to remember that a plentiful source of future interest in and support of the TLM will come from those fortunate Catholics who are brought up in (or who seek out) communities that embody the hermeneutic of continuity. For these Catholics, the step to the TLM is much more natural; it is like meeting a long-lost relative of the same family, rather than a stranger from a foreign country. Between the current situation of a minority presence of the EF and the future situation of a predominance of it, there will need to be a middle period characterized by parishes across the country that, to put it in a nutshell, have both the Campion Missal and the Jogues Missal in their pews.

The patron of this new book, Saint Isaac Jogues, S.J., knew long before the Second Vatican Council that the Mass is the source and summit of the life and mission of the Church—which is why, even after his thumb and forefinger had been cut off during his enslavement and torture by the Iroquois, he was willing to return to the Indian missions and to continue offering this great Sacrifice, for the salvation of the world. Our attitude should not be any less radical than his when it comes to giving God the greatest and the best we can.

For more information, videos, and reviews, see the Jogues Missal site.

![]()

We are living in the midst of a veritable renaissance of beautiful new resources for celebrating the liturgy of the Roman Rite in both forms. It is as if, at last, the best of our tradition and the best prescriptions of Sacrosanctum Concilium are coming together for the benefit of the faithful. There is a kind of momentum building for the hermeneutic of continuity. Where just a few years ago it was hard to find the Propers of the Mass in vernacular plainchant, today there is a plethora of options, along with many fine articles explaining the whys and wherefores; where publications for the old rite were out of print and/or outrageously expensive, today there are reprints and new editions pouring forth from the presses.

The new liturgical movement is finding its singing voice and its material means for long-term growth and expansion. In this sense, although the Reform of the Reform faces enormous difficulties and the resurgence of the traditional Latin Mass has an uphill climb, there is also the hope of real progress after 40 years of the People of God wandering in the desert. Pastors and chaplains, musicians and music directors, DREs, everyone involved with the liturgical life of the Church, finally have fantastic products to choose from that can guide and sustain their pastoral programs for years to come. An example for the Ordinary Form would be the Lumen Christi Simple Gradual, reviewed here by NLM's David Clayton; an example for the Extraordinary Form would be the Saint Edmund Campion Missal & Hymnal, which I reviewed here.

It is to another project associated with Corpus Christi Watershed that I now turn my attention: the recently released Saint Isaac Jogues Illuminated Missal, Lectionary, and Gradual. (I should note that while Jeffrey Ostrowski was chief editor of this book and promotes it via the CCW website, it is the fruit of a group called the Pope John Paul II Institute for Liturgical Renewal.) There is a lot to say about this multi-layered book, a true labor of love and a work of beauty from start to finish. I could sum up my reaction by saying that the Jogues Missal does for the Ordinary Form what the Campion Missal does for the Extraordinary Form.

As its full title indicates, the Jogues Missal brings together the rich texts of the Roman Gradual (i.e., the Introit, Gradual, Alleluia or Tract, Offertory, and Communion antiphons) and the readings of the Lectionary (including responsorial psalms and Gospel acclamations) and places in their midst a magnificent full-color Order of Mass (pp. 251-314). Like the Campion Missal, the Jogues Missal is for Sundays and Solemnities of the Church year. Unlike the Campion, which includes a substantial hymn section, the Jogues is simply for following along with the texts and ceremonies of the liturgy; a planned companion volume, the Saint Isaac Jogues Hymnal, will be a dedicated music resource with hundreds of hymns, but there is no particular reason that the Jogues Missal could not be paired with other musical resources such as the Lumen Christi Simple Gradual. (The Jogues Missal does include a modest amount of music: Chabanel Psalm setting for each Mass; Sequences in metrical English versions with simple tunes, with the original Latin texts and literal translations in an appendix; a couple of hymns for Benediction; and the Mass in Honor of St. Isaac Jogues, a plainchant setting that includes the Creed.)

When I first opened the package, I was blown away by the aesthetic qualities of the Jogues Missal. The elegance of the page layout is perhaps what strikes the eye first: graceful drop caps of hierarchically gradated size and design are used for various propers and readings, drawing the eye gently to their place in the liturgy; decorative borders set apart the different days; exquisite full-page black and white etchings for major feastdays, surrounded by Scripture verses, plunge us into the mysteries of God and the saints. These qualities render the book a truly worthy instrument for deeper interior participation in the sacred liturgy.

The Order of Mass section is the most striking feature of the Jogues Missal. I have access to a very large collection of liturgical books, and I regret to say that practically none of them manages to convey any conscious or subconscious impression that the Ordinary Form can be a beautiful thing. We have been plagued by utilitarianism and pragmatism for decades, and it often seems as if the traditional Latin Mass is the only surviving refuge for a heightened sensitivity to beauty in every last detail. What the Jogues Missal accomplishes in this regard is nothing short of astonishing. The photos call to mind the historic heritage of the Roman Rite: the glory of its musical heritage; the pregnant symbolism of the different parts and actions of the Mass, with a loving attention to details of ritual; the fittingness of suitable architecture and vesture; even the sacredness of particular words. There is a kind of programmatic “re-enchantment” of the missal that takes place in these pages, simply by the force of loving what the Church herself offers and not filtering it through a reductionistic Bauhaus lens.

This brings me to an interesting angle: the Jogues Missal as an instrument of liturgical renewal and reform. It is no secret that the way the OF Mass is celebrated in most communities bears little likeness to the images represented in this missal's pages. The celebrating priest is displayed wearing a maniple (e.g., p. 263 and p. 277) which matches his ornate red and white chasuble; the altar server is in cassock and surplice, and even the men’s schola is similarly attired (p. 273). One lady is wearing a mantilla (p. 265). Mass is being celebrating ad orientem towards a Gothic high altar with six lit candles and a statue of Our Lady (e.g., p. 266, p. 300); naturally, incense is featured (p. 276). The chalice is gloriously ornate gold and silver (e.g., p. 292). The priest holds his thumb and forefinger together after consecration (p. 300). Holy communion is distributed on the tongue to those who are kneeling (p. 310). And throughout, the assumption is that the Propers are being chanted, whether in the vernacular or in Latin (the second color image, on p. 252, is of a Gregorian chant manuscript with an Introit). Indeed, the very first color image (p. 251; see below) is a Crucifixion-Trinity scene surrounded by the nine orders of angels, with a priest at the bottom raising the chalice ad orientem: a paradigm of the entire approach here, which could be described as “ROTR to the Max.”