On 19 February 1513 Pope Julius II signed a papal bull in which he constituted the Cappella Giulia, the Choir of St Peter’s, which has been celebrating its 500th anniversary this year. The Vatican Post Office has released a special set of postcards (see images below) featuring some of the most famous of the Choir’s Magisters.

Prior to 1512, musical arrangements at St Peter’s were very ad hoc, although from 1509 onwards there were signs of attempts to build up the music with a pool of musicians, of somewhat fluid membership, which provided cantors. Pope Julius II wanted a chapel in which the Divine Liturgy would be celebrated beautifully every day. His Cappella Giulia, which was to be his mausoleum, was intended to be part of the new basilica which was being built at the time. His uncle, Pope Sixtus IV, had built the Cappella di Palazzo, better known as the Sistine Chapel, and it was this which undoubtedly provided Pope Julius with the inspiration to build a new chapel with music to rival that of the Sistine.

At the beginning of 1513, Pope Julius was gravely ill. On 19 February, the day before he died, he signed the bull In altissimo militantis Ecclesiæ founding the choir of the Cappella Giulia and making provision in perpetuity for 12 boys and 12 men to sing in the chapel. Specifically, Italians were to be employed, as opposed to the largely French and Spanish musicians who worked in the Sistine. The Pope died the very next day and his mausoleum was never built. It would have been truly pharaonic, with Michelangelo’s Moses being just one of forty statues. In its place today is the Altar of the Chair. The first few years of the choir were turbulent times: there were financial difficulties in the first years, then the sack of Rome in 1527 followed by the reconstruction of the city, and then a plague.

In 1551, Palestrina was appointed as ‘Magister cantorum’ and he immediately increased the number of cantors in the choir. On his departure in 1554 to the Sistine Choir, Animuccia took over. Palestrina’s time at the Sistine was in fact short-lived as he and a number of the cantors there were asked to leave when the new Pope decided only to employ men in minor orders in the Chapel. As a married man, Palestrina was ineligible. Both Palestrina and Animuccia combined their duties with the Chiesa Nuova, the Roman Oratory, just as the current Magister, Fr Pierre Paul, does today.

Animuccia was a very prolific composer, however most of his huge output was lost in the 1700s when his scores were sold to a shopkeeper near St Peter’s to be used to wrap cheese, the music being considered passé. On Animuccia’s death in 1571, Palestrina returned to the Cappella Giulia where he remained until his own death in 1594. In 1979 the Cappella Giulia ceased for financial reasons, but was reinstated with women sopranos in May 2008.

In many ways the Cappella Giulia is musically more interesting than the Sistine Choir; whilst the Sistine had a relatively limited library of fixed repertoire, such as the famous Miserere by Allegri, the Magistri of the Cappella Giulia, who were all expected to compose, brought a stylistic diversity coming as they did from a range of different cities. There are over 4000 titles in the Cappella Giulia’s archives which were recently catalogued by Canon Dario Rezza. The entire history of the Cappella Giulia has been recorded in a vast and comprehensive book in two volumes, complete with facsimiles of many of the most important documents. The author, Giancarlo Rostirolla has spent 30 years researching this book which will be available early next year.

The 2013 celebrations began at Mass on the Feast of the Chair of St Peter, and throughout the year a number of choirs have been invited by Fr Pierre Paul to sing with the Cappella Giulia for Sunday Mass in the Basilica. My own choir, the Schola Cantorum of the London Oratory School was the first of these choirs and sang with the Cappella Giulia last February at both Mass and Vespers. The complete list of choirs which have sung this year is as follows:

24 February, Schola Cantorum of the London Oratory School, England

10 March, St. Anne Catholic Church Choir, Houston TX, USA

17 March, St. Gregory the Great Church, Chicago IL, USA

7 April, St. Michael Cathedral Boys Choir, Toronto, Canada

5 May, Tokai Male Choir, Nagoya, Japan

12 May, Choir of St. Vincent de Paul, Huntington Beach CA, USA

30 June, Les Petits Chanteurs du Mont-Royal, Montréal QC, Canada

7 July, Les Petits Chanteurs de Trois-Rivières, QC, Canada

14 July, Assisi Music Festival Choir, Summit NJ, USA

21 July, St. Colman’s Cathedral Choir, Cobh Co. Cork, Ireland

28 July, Osnabrücker Jugendchor, Germany

18 August, Choeur de la Cathédrale Primatiale de Lyon, France

15 September, Monterey Diocesan Choir, Monterey CA, USA

20 October, St. Andrew Camerata, Edinburgh, Scotland

3 November, Combined choirs of Immaculate Conception Church, Durham NC, USA and St. Mark Church, Wilmington NC, USA

10 November, Saint Andrew Catholic Church, Newtown PA, USA

17 November, Saint John Cantius Parish, Chicago IL, USA

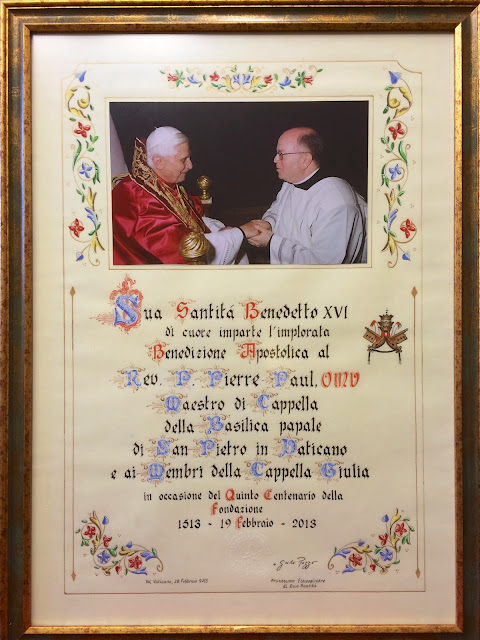

Hanging on the wall of Fr Pierre's office at the Vatican in pride of place is this wonderful photograph of him meeting Pope Benedict XVI.

|

| Ruggiero Giovanelli |

At the beginning of 1513, Pope Julius was gravely ill. On 19 February, the day before he died, he signed the bull In altissimo militantis Ecclesiæ founding the choir of the Cappella Giulia and making provision in perpetuity for 12 boys and 12 men to sing in the chapel. Specifically, Italians were to be employed, as opposed to the largely French and Spanish musicians who worked in the Sistine. The Pope died the very next day and his mausoleum was never built. It would have been truly pharaonic, with Michelangelo’s Moses being just one of forty statues. In its place today is the Altar of the Chair. The first few years of the choir were turbulent times: there were financial difficulties in the first years, then the sack of Rome in 1527 followed by the reconstruction of the city, and then a plague.

|

| Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina |

Animuccia was a very prolific composer, however most of his huge output was lost in the 1700s when his scores were sold to a shopkeeper near St Peter’s to be used to wrap cheese, the music being considered passé. On Animuccia’s death in 1571, Palestrina returned to the Cappella Giulia where he remained until his own death in 1594. In 1979 the Cappella Giulia ceased for financial reasons, but was reinstated with women sopranos in May 2008.

|

| Ernesto Boezi |

The 2013 celebrations began at Mass on the Feast of the Chair of St Peter, and throughout the year a number of choirs have been invited by Fr Pierre Paul to sing with the Cappella Giulia for Sunday Mass in the Basilica. My own choir, the Schola Cantorum of the London Oratory School was the first of these choirs and sang with the Cappella Giulia last February at both Mass and Vespers. The complete list of choirs which have sung this year is as follows:

24 February, Schola Cantorum of the London Oratory School, England

10 March, St. Anne Catholic Church Choir, Houston TX, USA

17 March, St. Gregory the Great Church, Chicago IL, USA

7 April, St. Michael Cathedral Boys Choir, Toronto, Canada

5 May, Tokai Male Choir, Nagoya, Japan

12 May, Choir of St. Vincent de Paul, Huntington Beach CA, USA

30 June, Les Petits Chanteurs du Mont-Royal, Montréal QC, Canada

7 July, Les Petits Chanteurs de Trois-Rivières, QC, Canada

14 July, Assisi Music Festival Choir, Summit NJ, USA

21 July, St. Colman’s Cathedral Choir, Cobh Co. Cork, Ireland

28 July, Osnabrücker Jugendchor, Germany

18 August, Choeur de la Cathédrale Primatiale de Lyon, France

15 September, Monterey Diocesan Choir, Monterey CA, USA

20 October, St. Andrew Camerata, Edinburgh, Scotland

3 November, Combined choirs of Immaculate Conception Church, Durham NC, USA and St. Mark Church, Wilmington NC, USA

10 November, Saint Andrew Catholic Church, Newtown PA, USA

17 November, Saint John Cantius Parish, Chicago IL, USA

Hanging on the wall of Fr Pierre's office at the Vatican in pride of place is this wonderful photograph of him meeting Pope Benedict XVI.

Choirs of sufficient standard who wish to sing at St Peter’s should contact Fr Pierre Paul directly.

.jpg)