Pursuant to Dr. Kwasniewski’s

recent article on the Scriptural readings of the Roman Rite, I propose to follow up with a small series of articles on the historical tradition of the Roman Mass lectionary. The first question which I wish to address is, “Did the Roman Rite anciently have three readings, which were later cut back to two?” The corollary question which inevitably rises from this is, “Does the three-reading system of the post-Conciliar lectionary represent a return to the ancient practice of the Church?” A positive answer is, of course, not a definitive argument in favor of a three-reading system, and a negative answer is not a definitive argument against it.

The short answer, however, is No.

Like so much of the post-Conciliar reform, the theory derives in no small part from the close proximity of the Roman Rite to the Ambrosian. In the Ambrosian liturgy, the standard pattern for the readings on Sundays and major feasts is:

1. Prophecy

2. Psalmellus (the Ambrosian equivalent of the Gradual)

3. Epistle

4. Alleluia (always spelled “Halleluiah” in Ambrosian liturgical books)

5. Gospel.

The Psalmellus is constructed similarly to the Gradual in both form and text, which is most often taken from the Psalms. In Lent, the Halleluiah is substituted by a “Cantus”, as the Roman Rite substitutes a Tract. The most notable difference is that the Psalmellus is not changed to a Halleluiah in Eastertide; but even in the Roman Rite, this change is made not on Easter itself, but on Low Saturday.

On the basis of this pattern, the assumption was made that the Roman Rite originally also had a Prophecy, followed by Gradual, Epistle, Alleluia and Gospel. At some point, (usually said to be the sixth century, as e.g. Fr. Keith Pecklers’

Genius of the Roman Rite, p. 12; Burns and Oates, 2009), the Prophecy was dropped, and the Gradual transposed after the Epistle.

Several arguments might be adduced from various other sources in favor of this idea. Three readings “remains” the pattern in the Roman Rite on a very limited number of days, understood to be holdovers of the more ancient practice. (These are Good Friday, and the Wednesdays of the Embertides, of the fourth week of Lent, and of Holy Week.) The Mozarabic Rite follows a similar pattern with three readings, although Alleluia is sung after the Gospel. The Gallican liturgy used in France before Charlemagne’s time had three readings. The ancient church of Saint Clement in Rome, along with a few others like it, has three ambos; it was believed that each one was for one of the three readings. Some Eastern Rites, such as the Syriac and Coptic, have two or even three readings before the Gospel. The Byzantine Liturgy has only the Epistle, Alleluia and Gospel, suggesting perhaps a prior form in which both the Prophecy and the chant that followed it were allowed to drop. Certain passages from the Fathers refer to, or may be understood to refer to, the presence of more than one reading before the Gospel. Lastly, all historical Christian liturgies are in agreement that whatever arrangement and number of readings, the Gospel comes last, a point which seemed to indicate a common tradition.

Taken all together, these arguments seemed to close the case. The (formerly) definitive formulation of the theory was made by Msgr. Louis Duchesne in the book

The Origins of Christian Worship: A Study of the Latin Liturgy before Charlemagne. (Origines du culte chrétien: étude sur la liturgie latine avant Charlemagne, Paris 1898.) His conclusions were almost universally accepted. We find him cited repeatedly, for example, by Fr. Adrian Fortescue, who writes in the original Catholic Encyclopedia

entry on Lessons in the Liturgy, “The Roman Rite also certainly once had these three lessons at every Mass.”

Duchesne’s theory has only two significant drawbacks: a complete lack of manuscript evidence, and the complete lack of any conclusive point in its favor.

The placement of the Gospel as the culmination of any series of Biblical readings in a Christian liturgy is too obvious a choice to prove anything; there is no need to posit any

specific common liturgical tradition from which it must derive. The Patristic sources are neither conclusive or very specific about the arrangement of readings at the Mass; some appear to suggest that there were two, and others three. The Eastern liturgies shed no real light on the question as it relates to the Roman Rite. Even the most cursory look at the Byzantine lectionary, and the chants sung before and between the two readings, show that they derive from a completely independent tradition. The same holds true for the Mozarabic and Gallican Rite.

The

three ambos in St. Clement’s are a very weak point for Duchesne’s theory. It was formerly explained that of the two on the right side of the church, the lower was for the Prophecy, and the higher for the Epistle. The lower one, however, faces the door of the church, while the higher faces the altar. It should be obvious that if there were a Prophecy before the Epistle, it would also be read facing the altar, which represents Christ, to demonstrate that the Old Testament is about Christ. The Church Fathers took great pains to assert this very point against the heresies which denied the value of the Old Testament, and to assuage doubts about it of the sort which St. Augustine mentions in the Confessions. (IX, 5) For this and other reasons, scholars now agree that the “third” ambo was actually for the leader of the schola cantorum.

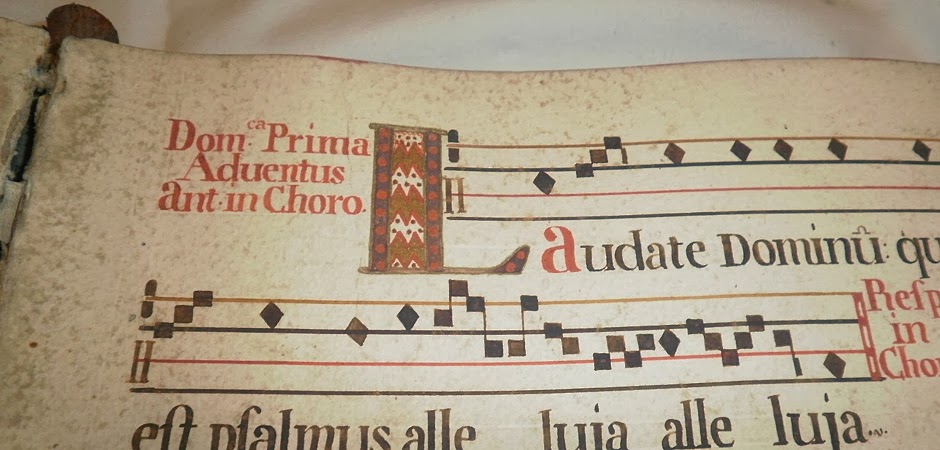

![]() |

| The two ambos of the 8th-century church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome; that seen here on the left is for the Epistle, and the one on the right, with the stand for the Paschal next to it, is for the Gospel. The arrangement of the choir is very similar to that of San Clemente. |

Of the seven days on which there are two readings at the Mass before the Gospel, six are Wednesdays, and one is Good Friday. Here it is hard to understand how scholars like Duchesne and Fortescue could have thought that the Church of Rome would throw out an ancient pattern of readings

almost entirely, but keep it on such a purely random selection of days. In the same entry of the Catholic Encyclopedia cited above, Fr. Fortescue writes, “At Rome, too, the lessons were reduced to two since the sixth century (‘Liber Pontificalis’, ed. Duchesne, Paris, 1884, I, 230),

except on certain rare occasions.” (my emphasis). The passage cited from Duchesne’s famous edition of the

Liber Pontificalis says exactly the opposite of what he supposes it does: “Celestine (I, 422-32) … established that before the Sacrifice, the 150 Psalms of David (i.e. texts from them) should be sung in alternation by all. This was not done before, but there were recited only the Epistle of blessed Paul, and the Holy Gospel.” (To be fair, the Latin of the

Liber Pontificalis is atrocious, and the manuscripts full of variants.)

In point of fact, what these Masses have is not an older pattern of readings, but an interpolation into the standard order of Mass. The interpolation must, however, be understood as not

just an extra reading, but a group of three elements: a collect, precede by “Oremus. Flectamus genua. Levate.”, a reading, and a gradual. These three elements are inserted as a unit after the Kyrie, once on the aforementioned Wednesdays, and five times on the Ember Saturdays. On Good Friday, the interpolation appears in the Missal of St. Pius V in an attenuated form, without the first prayer (or the “Oremus etc.” before it); a slightly mangled version of it was restored in the reform of Pius XII. In Pentecost week, the genuflection is dropped, and the Gradual is substituted by an Alleluia, in keeping with the customs of Eastertide. At none of these Masses is the second reading from an Epistle of the New Testament.

The final point to make here, and the one which

should have been decisive against Duchesne’s theory, is that there is not a single liturgical manuscript of any kind which refers in any way to a putative system of three readings in the Roman Rite. All surviving lectionaries of the Roman Rite, and all other manuscripts which refer to the readings, agree on the two reading pattern. This point should carry the argument, because although lectionaries occasionally contain other elements, they are primarily anthologies of the Sacred Scriptures. As such, they were treated with the same reverence as the Bible itself, and are among the most likely to be carefully preserved; and indeed, among the very oldest surviving liturgical manuscripts of the Roman Rite is the famous lectionary of Wurzburg, written about the year 700. (Likewise, it may also be noted that the other liturgical books of the pre-Carolingian Gallican Mass are too few and too incomplete to permit a reconstruction of it, but several lectionaries of that rite do survive.)

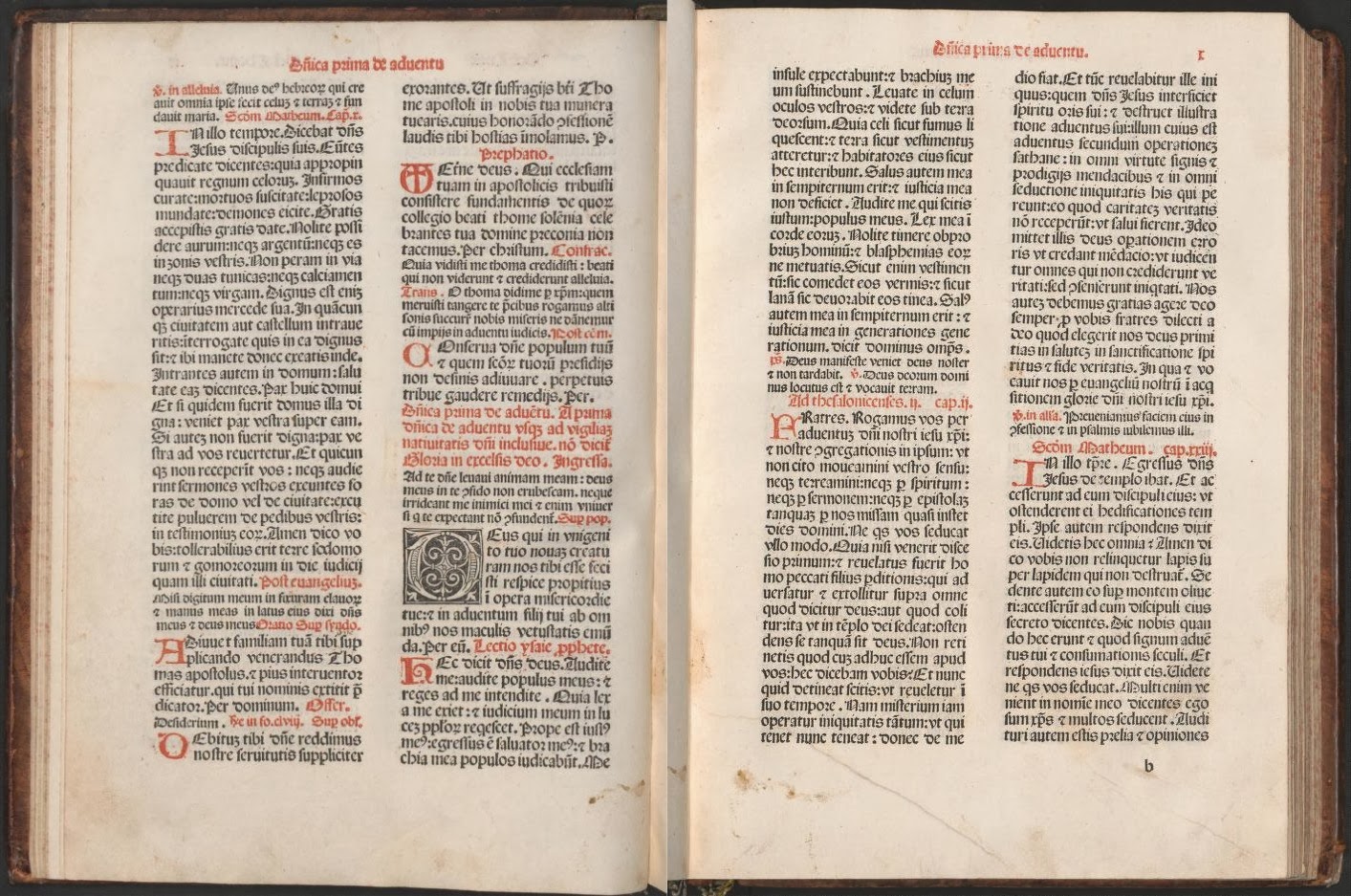

![]() |

| The first lesson of the 9th century book of Epistles known as the “Lectionary of Alcuin”, Romans 1, 1-6, to be read at the Mass of Christmas Eve Day, as also in the Missal of St. Pius V. (Early Roman lectionaries usually begin with Christmas, and place Advent at the end.) Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Latin 9452 |

In the next article in this series, I will consider the evidence of the Ambrosian liturgy in relation to this question.

.jpg)