Guest article by Jeff OstrowskiThe following article is the conclusion of a six-part series in which it has been my great honor to discuss various aspects and "highlights" of the 992-page

St. Edmund Campion Missal & Hymnal for the Traditional Latin Mass. The subject of the following piece is "Rare Hymns written by the English Martyrs," and I shall begin by providing the rationale for our inclusion of the martyrs' poetry. The website has several essays that constitute further reading on the subjects discussed below, and here is the URL:

*

ccwatershed.org/Campion

Our Missal began shipping last week, and many have received their copies. The

Rorate Caeli Blog has posted a "first look," showing images of the actual book pages, as well as

pictures of the book cover. Readers might also appreciate a special

video presentation with instructions on how to use the Campion Missal.

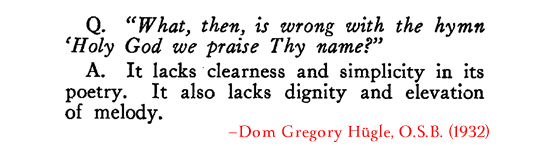

In my experience, few subjects make a Church musician's blood pressure rise as quickly as discussion of hymns and hymn tunes. For some reason, it is intensely personal. My fervent hope is that if the reader happens to disagree with any of my statements, he will quickly remember the Latin phrase "De gustibus non est disputandum" (

About taste, let there be no dispute). It would be unrealistic to pretend that all will agree perfectly with every point, and I would draw the reader's attention to the following excerpt:

![]()

Dom Gregory was very well respected in the field of Church music. For him to make such a statement about a universally respected hymn like "Holy God, We Praise Thy Name" strikes me as a wonderful reminder of the aforementioned Latin motto!

In

Part 1, I touched briefly on what is sometimes called the

"Mother Dear, Oh Pray for Me" syndrome. Others refer to it as the "Bring Flowers of the Rarest" syndrome. Summarized briefly, a significant portion (many would say "a majority") of devotional hymns sung in the vernacular at Catholic Masses before the Second Vatican Council were of a very low quality. Although theologically sound, they were uninspired and saccharine. Fr. Fortescue was not using hyperbole when he said, "The real badness of most of our popular hymns, endeared, unfortunately, to the people by association, surpasses anything that could otherwise be imagined." This is significant because the vernacular music

following the Second Vatican Council was so deplorable it became common to assume that whatever was

before the Council must have been magnificent.

The "Bring Flowers of the Rarest" affliction is well known and frequently noted by Catholic authors. However, what is not generally realized is that many of these same Catholic hymnals also suffered from an

additional defect, and a serious one: they often failed to specify the name of the hymn tune. As one might imagine, when the hymn tunes are not even mentioned, such books did not include hymn tune indices.

Let me take heed here, before I lose the "non-musician" reader unfamiliar with the notion of a "hymn tune." These readers might profit from this

basic overview of the subject. In any event, just as humans are made up of body & soul, hymns are made up of text & melody ("tune"). To understand this is

of the utmost importance, as choirmasters must realize they are free to pair great hymn tunes with a

variety of texts, no matter what pairing choices editors made in their publications. The English understand this and never print words underneath the melodies — for various reasons — one reason being that folks might begin to assume there is a "correct" tune for a given text. The English also understand that several hymn tune indices are absolutely essential. Sadly, American publishers to this day do not seem to realize this. I have before me a famous 825-page hymnal by one of the "big three" Catholic publishers, and it does not contain a single index for hymn tunes (metrical, alphabetical, etc.). I was trying to look up a tune harmonization and was unable to do so, because (needless to say) I have no idea which text their editor paired to that tune.

A musician ought never pair text & tune willy-nilly: pairing requires sensitivity and knowledge. Having looked at the following three (3) examples, I would invite the reader to please use the "com box" to say whether you agree the following text/tune pairings are

grotesque (although they might not have sounded odd at the time of publication). I will not provide the tune names, as that would spoil the fun:

*

Example 1 pairs an Easter text.

*

Example 2 pairs a text by Fr. Robert Southwell.

*

Example 3 pairs "At the Lamb's High Feast."

Bearing all these things in mind, my task as editor of the Campion Hymnal was fairly straightforward: find only the finest texts and pair them with the most excellent tunes. What makes a good tune?

![]()

I think Dom Gregory's definition is fine, but hardly complete. At the conservatory where I studied, we had entire courses in melodic composition, and one word that came up constantly was "balance." In this

excellent article by Sir Richard Terry, he tries to explain what qualities make a hymn tune good, and I think he does a fairly nice job.

In any event, I have a confession to make: I could not be more excited about the hymn tunes in the Campion Hymnal. The tunes are simply marvelous: WHITEHALL, BRESLAU, ALL SAINTS, REGENT SQUARE, DIX, FESTAL SONG, RUSTINGTON, DUGUET, LAUDA ANIMA, WINCHESTER NEW, THAXTED, EISENACH, SALZBURG . . . the list continues on and on. It reminds me of a phrase by Horowitz, as quoted in Dubal's

Evenings With Horowitz, "Each Mazurka is pure gold. One is better than the other. I heard my mother playing a Mazurka when I was five years old. I cried. Can you imagine? I know these Mazurkas for eighty years, yet Chopin himself only lived to be thirty-nine!" Horowitz (not a native speaker of English) often used that phrase or some variation of it, such as, "Each one is better than the last." His point was that

each one is amazing, special, fresh, wonderful — and this is how I feel about the beautiful hymn tunes chosen for the

Campion Missal & Hymnal. Furthermore, the eleven (11) tunes Maestro Kevin Allen composed specifically for our book are truly outstanding and exceeded our wildest hopes. As mentioned in

Part 1, we also made sure to include all the hymns well-known to Traditional communities, because a hymn book ought to contain a mixture of "fresh" hymns and familiar ones.

Where did our hymn texts come from? First of all, we scoured rare texts by the very best hymn writers and translators: Neale, McDougall, Caswall, etc. The Campion Hymnal actually uses more texts by Bl. John Henry Cardinal Newman than any other collection (by design). Furthermore, many of the hymns are beautiful English translations of ancient Latin hymns, as can be seen by

this list.

In honor of Edmund Campion, we included a whole host of hymn texts by his fellow English martyrs (like St. Thomas More), and many of these have never before been set to music. Several of these texts were written in the Tower of London, as the particular saint was awaiting martyrdom. It is my ardent hope that these texts will inspire Catholics to study the English martyrs' biographies, which are both fascinating and inspiring.

In an article such as this, it is not possible to relate the enthralling details of the lives of the English martyrs, but I would like to share just a few examples of the texts we chose. Below are some excerpts by St. Robert Southwell, an English martyr and Jesuit priest (like Edmund Campion), whose poetry was greatly admired by William Shakespeare.

1. The following is an excerpt from a hymn with meditations on the heavy weight of sin. We of the 21st century tend not to think about sin very often; or at least we don't let sin bother us too much. We are too busy with other things to be worried about a little thing like offending Almighty God. St. Southwell's reflection reminds us of our folly. Paired with an appropriate tune, it was placed in the "Lent & Passiontide" section.

This globe of earth doth thy one finger prop, The world thou dost within thy hand embrace; Yet all this weight of sweat drew not a drop, Nor made thee bow, much less fall on thy face; But now thou hast a load so heavy found, That makes thee bow, yea fall flat to the ground.

2. We included a very long hymn which is a

truly magnificent reflection on the miracle of the Holy Eucharist by Fr. Southwell. As with all of Fr. Southwell's works, there were many variants to choose from, some dramatically different. My hope is that scholars of Robert Southwell will contact me, letting me know if there are reasons to prefer one variant over another. Perhaps two verses will give the reader an idea of the splendor of this text, which we paired with a famous and stately tune:

One soul in man is all in every part; One face at once in many mirrors shines; One fearful noise doth make a thousand start; One eye at once a thousand things defines; If proofs of one in many Nature frame, God may in stronger sort perform the same. What God, as author, made, He alter may; No change so hard as making all of nought; If Adam fashion'd were of slime and clay, Bread may to Christ's most sacred flesh be wrought: He may do this, that made, with mighty hand, Of water wine, a snake of Moses' wand.

3. Fr. Southwell's beautiful reflection on the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary is also included, and paired with a splendid tune by composer Kevin Allen. Here is an excerpt:

Our second Eve puts on her mortal shroud, Earth breeds a heaven for God's new dwelling-place; Now riseth up Elias' little cloud, That growing shall distil the showers of grace; Her being now begins, who, ere she ends, Shall bring our good that shall our evil mend.

4. "The Virgin's Salutation" by Fr. Southwell has obvious echoes of the

Ave Maris Stella:

Spell "Eva" back and "Ave" shall you find, The first began, the last reversed our harms: An angel's witching words did Eva blind, An angel's "Ave" disenchants the charms: Death first by woman's weakness enter'd in, In woman's virtue life doth now begin.

Being that our organization is named in honor of Corpus Christi, I desired to set musically Fr. Southwell's

metrical translation of the Lauda Sion for "Corpus Christy Daye," but the meter could not be made to fit. Like many Catholic translators who followed him, Fr. Southwell was afraid to alter the theology in any way, and this necessitated "irregular and questionable rhymes" and "halting rhythm." Monsignor H. T. Henry explains with great detail in

this fascinating excerpt from his

Eucharistica. Here's the relevant passage:

In general, Catholic translators have sacrificed the original rhythm in the interest of fidelity to the thought . . . it may be said that Catholic translators have sought fidelity first of all, while non-Catholics have been willing to depart from this requisite, partly for doctrinal, partly for poetical reasons.

Regarding the use of vernacular hymns at the Traditional Latin Mass, we absolutely refrained from endorsement of any particular practice. Those decisions ought to be made by the choirmaster and pastor, having thoroughly researched Church teachings on this matter (especially §14b,

De musica sacra et sacra liturgia, 1958). However, it is important to realize that, throughout history, there were some instances of vernacular hymnody being used at the Latin Mass. The "Missionary Masses" (treated so well by Claudio R. Salvucci) and the so-called "German High Mass" would be two examples.

That being said, it is also important to realize the

limits of these exceptions. By relating the following example from the

Second International Congress of Catholic Church Music, Vienna, 1954, I hope this will become crystal clear.

Those who wished to expand the practice of vernacular hymns at Mass ("replacing the Mass" rather than "praying the Mass") would find a powerful advocate in Rev. Clifford Howell, S.J., whose

informative and articulate article ought to be read by anyone interested in the history of the Roman Rite. However, another perspective is given by Msgr. Charles Meter in his

valuable synopsis of the 1954 Congress in Vienna. (I also included in that PDF a 1955 letter from Fr. Reinhold, condemning Fr. Howell's piece.) Msgr. Meter's piece is without a doubt "required reading," and here are a few excerpts:

Here we were to attend a Missa lecta which would demonstrate the Volksgesang Mass, wherein the people sing their parts in German. This idea originated with FR. PIUS PARSCH, the famous liturgist of Klosterneuburg, who died only a short time ago. (Incidentally, the October issue of CAECILIA Magazine contained an article by Fr. Howell, S.J., giving a complete description of this strange type of Mass.) Frankly, we were all quite shocked at what we heard and saw! All this seemed directly opposed to the Motu Proprio of Pius X where he speaks of the liturgical text: "The language proper to the Roman Church is Latin. Hence it is forbidden to sing anything whatever in the vernacular in solemn liturgical functions — much more to sing in the vernacular the variable or common parts of the Mass and Office." Obviously this was not a mere Low Mass since the celebrant chanted his parts and was obliged to wait until the choir and congregation had finished singing their parts. I am afraid I shall have to differ with Fr. Howell about the appropriateness of this new type of Mass. Rome is quite concerned these days about some of these innovations; and as a mater of fact MSGR. MONTINI on the part of the Holy Father sent a special letter to Cardinal Innitzer of Vienna in which he stressed the fact that the Latin language must be retained. It is true that the people should take a more active part in the Mass, but that does not mean they must sing the Mass in the vernacular . . . [a few paragraphs later] The Thursday we went out to Klostemeuburg Monastery to attend that highly controversial Betsingmesse, all lecture sessions were held in the Hall of the Monastery. The famous Jesuit liturgist, DR. JUNGMANN, S.J., addressed us after the Mass. Stressing the importance of lay participation in the Mass, he went so far as to say that the ideal is to let the people sing their parts of the mass in the vernacular so that they may better understand what they are singing. Then, of course, he referred to the votum of the Liturgical Congress in Lugano, which made an appeal to Rome for the vernacular even in a High Mass. As soon as Fr. Jungmann finished, MSGR. IGINIO ANGLES of Rome stood up and, though regretting that he had to speak as he did, was obliged publicly to condemn this proposal of the learned liturgist. He produced the letter from Msgr. Montini stating that the Latin language must be retained, except in those places where Rome has by way of exception allowed the people to sing in the vernacular at a High Mass, such as the so-called Diaspora in Germany. Quite obviously the audience agreed with Msgr. Anglés, except for a small group who had defended this type of the Betsingmesse celebrated that morning in the Monastery Church — a Low Mass chanted recto tono by the celebrant with the choir and people singing the Proper and Ordinary in German. It was evident from this session that the musicians' viewpoint is to preserve the Latin in the High Mass while that of a small group of more outspoken liturgists is to introduce the vernacular wherever possible.

For those unaware, MSGR. IGINIO ANGLES was President of the 1954 Congress and likewise president of the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome. Many readers probably know that MSGR. MONTINI later became His Holiness, Pope Paul VI. People had different opinions about Pope Paul VI's positions on Church music. Monsignor Richard Schuler, in

an article referred to Paul VI as the "Pope of Sacred Music," but Domenico Cardinal Bartolucci once said, "Then came Paul VI, but he was tone deaf, and I don't know how much of an appreciation he had for music."

Although we have no official position on the extent to which vernacular hymns should be used at Low Mass, it seemed obvious to us that most Traditional parishes without fail sing a Recessional Hymn in the vernacular after High Mass. Sadly, many communities are forced to sing a handful of hymns over and over again (especially

Holy God, We Praise Thy Name) due to a complete dearth of suitable hymnals. This was the reason for our efforts in this area: so that Traditional communities will henceforth have 150 sublime hymns to choose from each week, no matter what the liturgical season.

Previous Installments: Part 1 •

Part 2 •

Part 3 •

Part 4 •

Part 5![]()