The Cathedral of the Sacred Heart in San Angelo, Texas, will have a Missa Cantata in the Extraordinary Form for the feast of the Holy Innocents on Thursday, December 28, with Palestrina’s Mass Aeterna Christi Munera; His Excellency Michael Sis, the bishop of San Angelo, will be in attendance and preach. The Mass begins at 6 pm; the cathedral is located at 19 South Oakes Street.

Mass for the Holy Innocents in San Angelo, Texas

↧

↧

A Proper Hymn for St Stephen

The Roman Divine Office is traditionally much more conservative than other Uses in the adoption of new texts, and this is particularly true in regard to its use of hymns. Of the 39 Saints named in the Roman Canon apart from the Virgin Mary, only John the Baptist and the Apostles Peter and Paul have their own hymns, the latter only at Vespers; all the rest have hymns taken from the common offices. Of the seven common offices of Saints, only that of Several Martyrs has a separate hymn for each of the three major hours. The Virgin Mary’s common office, adapted from the Office of the Assumption, also has three hymns, which are used on nearly all of Her feasts, in the Saturday Office, and in the Little Office as well. Exceptions like the Matins hymn of the Immaculate Conception are quite late.

One of the gems which is therefore not found in the historical Roman Use is a proper hymn for St Stephen, Sancte Dei pretiose; it was used by the Old Observance Carmelites, Premonstratensians, and the Use of Sarum, just to name a few. Most of these Uses have it at either Matins or Lauds, with the common hymn for one martyr at Lauds or Matins, and again at Vespers. When it originally composed in the 11th century, it had only three stanzas; a number of others were added to it later, but do not seem to have caught on. In this recording, the music turns into a kind of early polyphony at the 2:00 mark; but the second stanza is then repeated, and the doxology is not included.

One of the gems which is therefore not found in the historical Roman Use is a proper hymn for St Stephen, Sancte Dei pretiose; it was used by the Old Observance Carmelites, Premonstratensians, and the Use of Sarum, just to name a few. Most of these Uses have it at either Matins or Lauds, with the common hymn for one martyr at Lauds or Matins, and again at Vespers. When it originally composed in the 11th century, it had only three stanzas; a number of others were added to it later, but do not seem to have caught on. In this recording, the music turns into a kind of early polyphony at the 2:00 mark; but the second stanza is then repeated, and the doxology is not included.

| Sancte Dei pretiose Protomartyr Stephane, Qui virtute caritatis Circumfultus undique Dominum pro inimico Exorasti populo. | O Precious Saint of God, Stephen, the First Martyr, Who, by virtue of charity Surrounded on every side Didst pray to the Lord For the hostile people. |

| Funde preces pro devoto Tibi nunc collegio, Ut, tuo propitiatus Interventu, Dominus Nos, purgatos a peccatis Jungat caeli civibus. | Pour forth prayers now for The assembly devoted to thee, That, appeased by thy inter- vention, the Lord, may cleanse us from sin, And join us to the citizens of heaven. |

| Gloria et honor Deo Usquequaque Altissimo, Una Patri, Filioque, Inclyto Paraclito, Cui laus est et potestas Per aeterna saecula. Amen. | Glory and honor to God The most high in every place; The same to the Father, and the Son, to the glorious Paraclete; to whom belong praise and might for all ages. Amen. |

↧

Time for the Soul to Absorb the Mysteries — Part 4: The Ablutions to the Last Gospel

Last week I considered how the Communion rite in the traditional Mass afford a spacious home for corporate and personal prayer, so that the virtue of actual devotion, which is required for fruitful communication, may thrive in clergy and in laity alike. One may say, in fact, that the traditional Mass continually supports and strongly encourages the positing of all the acts of the virtue of religion discussed by St. Thomas Aquinas in the Summa, such as devotion, prayer, adoration, sacrifice, and praise.[1] In this way, the Mass is not only an “oasis” of peace in which prayer may be kindled and fed, but also a training or proving ground for the heavenly Jerusalem, whose citizens heroically exercise just these virtues. (Links to Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.)

Today I shall continue my exploration with the rites that take place once the priest and the faithful have received the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Our Lord.

The Ablutions

After communion, there is a long pause for the people while the priest cleanses his fingers and the sacred vessels, and the other ministers puts things aside or back to their places for the end of Mass. Here again we see the genius of the Roman Rite as it developed organically: there is no unseemly haste in this matter of ablutions, and, as a providential side effect, there need be no haste in the people’s time of thanksgiving. How welcome, how utterly necessary is this time of grace, when the Lord is most intimately present to and within us! Many great saints have spoken about the privileged prayer that is possible only at this time, in the minutes following sacramental communion with the Word made flesh. What a shame if the very form of the liturgy — or, it must be added, the particular customs of a given community, even in the sphere of the usus antiquior — should thwart this communion of minds and hearts!

The Placeat Tibi

Instead of racing to the finish line as the Novus Ordo does, in its eagerness to “send us out on mission,” et cetera ad nauseam, the old Mass takes a moment to beseech the Lord in a prayer of burning intensity, said by the priest bowing before the altar, in between the Ite missa est and the final blessing:

The Last Gospel

Over the years, one of the things about the Novus Ordo that has grated on me the most is the rapid-fire conclusion. The celebrant may well take his time with the homily (sometimes it seems as if this is viewed as the most important point of the entire Mass), but when it comes to everything afterwards, it’s “life in the fast lane” — particularly when communion is done. The vessels are hastily put away and “Let us pray” booms out like an ultimatum over the heads of people who could not have had the slightest chance to pray. Within seconds, the floodgates are opened and the crowds, impatient to get home to leisure pursuits that are vastly more significant than anything that happened on Calvary, pour into the parking lot to simulate bumper cars. It is thoroughly disedifying for the few devout Catholics who, due to some unanticipated freethinking, wish to stay in the pews to make their thanksgiving after Mass.

At a traditional Mass, this travesty is unheard of.[2] The liturgy itself builds in time for thanksgiving from the ablutions through the Placeat tibi and, finally, the sweet balm of the Last Gospel, which, no matter how slowly or quickly it is read, whether aloud or sotto voce, always seems like a well-placed comma or ellipsis in the grammar of worship. The end is rejoined with the beginning, like the circulation of divine lifeblood: In the beginning was the Word… the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, and we saw His glory… Deo gratias.

It is well to recall the beauty of the Last Gospel, the Prologue of the loftiest of biblical books, on this feast of its author, St. John the Evangelist. For it is he who teaches us, perhaps better than anyone else, the very virtue of restfulness in God that I have been arguing is one of the chief characteristics of the ancient Roman rite. The Beloved Disciple took his time at the Last Supper when leaning on the breast of Jesus; he did not think that there were more urgent things to do, be it selling ointments to get money for the poor, strategizing against the enemies of his Lord, or even preaching the good news that he was later inspired to write down. No, at the solemn moment when the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was instituted, John knew where he had to be and what he had to be doing: at the side of his Master, in the adoring silence of a friendship so intimate that it would later spill out in the most sublime revelations vouchsafed to man. John heard his Gospel beating in the heart of Jesus, High Priest and Victim; there he learned the meaning of adoration, reparation, supplication, and thanksgiving — Eucharistia. St. John is therefore the patron not only of theologians but of all who “worship God in spirit and in truth.” He leads us back, again and again, to the authentic liturgies of the Catholic Church, whose seeds the Lord sowed into the soil of His apostles’ souls in the Upper Room.

NOTES

[1] See Summa theologiae, II-II, qq. 81 to 91.

[2] Cf. my article "Priestly Preparation Before Mass and Thanksgiving After Mass."

Photos courtesy of and (c) Corpus Christi Watershed and Fr. Lawrence Lew.

Today I shall continue my exploration with the rites that take place once the priest and the faithful have received the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Our Lord.

The Ablutions

After communion, there is a long pause for the people while the priest cleanses his fingers and the sacred vessels, and the other ministers puts things aside or back to their places for the end of Mass. Here again we see the genius of the Roman Rite as it developed organically: there is no unseemly haste in this matter of ablutions, and, as a providential side effect, there need be no haste in the people’s time of thanksgiving. How welcome, how utterly necessary is this time of grace, when the Lord is most intimately present to and within us! Many great saints have spoken about the privileged prayer that is possible only at this time, in the minutes following sacramental communion with the Word made flesh. What a shame if the very form of the liturgy — or, it must be added, the particular customs of a given community, even in the sphere of the usus antiquior — should thwart this communion of minds and hearts!

The Placeat Tibi

Instead of racing to the finish line as the Novus Ordo does, in its eagerness to “send us out on mission,” et cetera ad nauseam, the old Mass takes a moment to beseech the Lord in a prayer of burning intensity, said by the priest bowing before the altar, in between the Ite missa est and the final blessing:

May the performance of my homage be pleasing to Thee, O holy Trinity, and grant that the Sacrifice which I, though unworthy, have offered up in the sight of Thy Majesty, be acceptable to Thee, and through Thy mercy, be a propitiation for me and for all those for whom I have offered it.A magnificent summary of the very essence of the Mass, and a summons to embrace its ascetical-mystical reality! The usus antiquior never forgets and never allows us to forget God’s majesty and our unworthiness, God’s mercy and our dire need of it. Centered from start to finish on the primal mystery of the Holy Trinity, serious about the Father’s business, the Mass is here simply styled “the Sacrifice.” That is what it is — and that is how it should look, sound, feel, and exist for us.

The Last Gospel

Over the years, one of the things about the Novus Ordo that has grated on me the most is the rapid-fire conclusion. The celebrant may well take his time with the homily (sometimes it seems as if this is viewed as the most important point of the entire Mass), but when it comes to everything afterwards, it’s “life in the fast lane” — particularly when communion is done. The vessels are hastily put away and “Let us pray” booms out like an ultimatum over the heads of people who could not have had the slightest chance to pray. Within seconds, the floodgates are opened and the crowds, impatient to get home to leisure pursuits that are vastly more significant than anything that happened on Calvary, pour into the parking lot to simulate bumper cars. It is thoroughly disedifying for the few devout Catholics who, due to some unanticipated freethinking, wish to stay in the pews to make their thanksgiving after Mass.

At a traditional Mass, this travesty is unheard of.[2] The liturgy itself builds in time for thanksgiving from the ablutions through the Placeat tibi and, finally, the sweet balm of the Last Gospel, which, no matter how slowly or quickly it is read, whether aloud or sotto voce, always seems like a well-placed comma or ellipsis in the grammar of worship. The end is rejoined with the beginning, like the circulation of divine lifeblood: In the beginning was the Word… the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, and we saw His glory… Deo gratias.

It is well to recall the beauty of the Last Gospel, the Prologue of the loftiest of biblical books, on this feast of its author, St. John the Evangelist. For it is he who teaches us, perhaps better than anyone else, the very virtue of restfulness in God that I have been arguing is one of the chief characteristics of the ancient Roman rite. The Beloved Disciple took his time at the Last Supper when leaning on the breast of Jesus; he did not think that there were more urgent things to do, be it selling ointments to get money for the poor, strategizing against the enemies of his Lord, or even preaching the good news that he was later inspired to write down. No, at the solemn moment when the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was instituted, John knew where he had to be and what he had to be doing: at the side of his Master, in the adoring silence of a friendship so intimate that it would later spill out in the most sublime revelations vouchsafed to man. John heard his Gospel beating in the heart of Jesus, High Priest and Victim; there he learned the meaning of adoration, reparation, supplication, and thanksgiving — Eucharistia. St. John is therefore the patron not only of theologians but of all who “worship God in spirit and in truth.” He leads us back, again and again, to the authentic liturgies of the Catholic Church, whose seeds the Lord sowed into the soil of His apostles’ souls in the Upper Room.

NOTES

[1] See Summa theologiae, II-II, qq. 81 to 91.

[2] Cf. my article "Priestly Preparation Before Mass and Thanksgiving After Mass."

Photos courtesy of and (c) Corpus Christi Watershed and Fr. Lawrence Lew.

↧

Christmas Photopost 2017 (Part 1)

As has been the case for the last couple of years, we have received a very large number of photographs of Christmas liturgies, we will be doing at least one other photopost of them, possibly more. They are posted mostly in the order they are received, so if you don’t see yours here, know that they will be posted in due time. We will also be doing photoposts for Epiphany; a reminder will be posted next week. In the meantime, we will be very glad to receive any photos of liturgies celebrated during the Octave of Christmas, the singing of the Te Deum on New Year’s Eve etc. Thanks to all those who have sent them in, and a blessed New Year to all our readers.

Holy Child Naval Chapel, Military Ordinariate of the Philippines - Fort Bonifacio, Taguig

St Paul - Birkirkara, Malta

St Anthony of Padua - Jersey City, New Jersey

Holy Child Naval Chapel, Military Ordinariate of the Philippines - Fort Bonifacio, Taguig

The Day Mass of Christmas, organized by the Societas Liturgiae Sacrae Sancti Gregorii

San Felipe Chapel - Los Angeles, California (FSSP)

Our Lady of Mt Carmel Pontifical Shrine - New York City

Oratory of Puerto Real de Iloilo - La Paz, Philippines

St Ignatius Chapel - St Inigoes, Maryland

Holy Cross Monastery - Chicago, Illinois

Ss Cyril and Methodius - Bridgeport, Connecticut

St Mary - Kalamazoo, Michigan

St Anthony - Des Moines, Iowa

Our Lady of the Pillar - Alaminos, Laguna, Philippines

↧

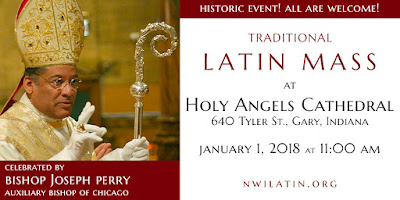

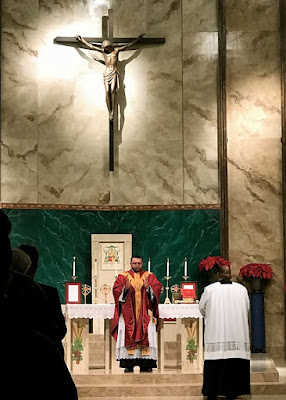

Octave of Christmas Pontifical Mass with Bishop Perry in Gary, IN, January 1

The Northwest Indiana Latin Mass Community announces that, for the first time in over 50 years, a Pontifical Latin Mass will be celebrated at Holy Angels Cathedral in the Diocese of Gary, Indiana. His Excellency, Bishop Joseph Perry, Auxiliary of Chicago, will visit to celebrate the Extraordinary Form Mass on January 1, 2018, at 11:00 AM. There will be special music for the occasion, with Gregorian chant and Renaissance choral polyphony. All are welcome to attend this historic event. The Cathedral is located on a beautiful campus at 640 Tyler St., Gary, Indiana. Further details and images are available at https://nwilatin.org/cathedral.

↧

↧

The Feast of the Holy Innocents 2018

Truly it is worthy and just, meet and profitable to salvation, that we praise Thee more gloriously, holy Father almighty, in the precious death of the little ones, whom because of the infancy of Thy Son, our Lord and Savior, the murderous Herod slew with monstrous savagery. We know the boundless gifts of Thy clemency; for grace alone shines forth greater than the will, and confession is glorious even before speech. Their passion came before there were any to share in His passion; they were witnesses of Christ, who could not yet recognize Him. Oh, the infinite goodness of the Almighty, when it did not permit the reward of eternal glory to perish for those slaughtered for His name, even though they knew it not; rather, as they were bathed in their own blood, the salvation of regeneration was accomplished, and the crown of martyrdom attributed to them. Through the same Christ our Lord. Through whom the Angels praise Thy majesty etc. (The Ambrosian Preface for the feast of the Holy Innocents.)

Vere quia dignum et justum est, aequum et salutare, nos in pretiosa morte Parvulorum te, Sancte Pater omnipotens, gloriosius collaudare: quod propter Filii tui, Domini nostri Salvatoris infantiam, immani saevitia Herodes funestus occidit. Immensa clementiae tuae dona cognoscimus. Fulget namque sola magis gratia, quam voluntas, et clara est prius confessio quam loquela. Ante passio, quam membra passionis existerent; testes Christi, qui ejus nondum fuerant agnitores. O infinita benignitas Omnipotentis: cum pro suo nomine trucidatis, etiam nescientibus, aeternae meritum gloriae perire non patitur; sed proprio cruore perfusis, et salus regenerationis expletur, et imputatur corona martyrii. Per eundem Christum, Dominum nostrum. Per quem majestatem tuam laudant Angeli etc.

|

| Reliquary of the Holy Innocents, 1449, from the Museum of the Basilica of St Ambrose. (Image from Wikimedia Commons by Sailko.) |

↧

Christmas Homily of Canon Francis Altiere

This past weekend, my family and I had the great joy of assisting at several Masses at the Institute of Christ the King's Oratory of Old St. Patrick's in Kansas City, MO. I was so struck by the homily Canon Altiere preached for the Christmas Masses that I asked him for (and gratefully received) permission to post the text of it at New Liturgical Movement, along with some photos from the Oratory. Enjoy!

![]()

CHRISTMAS HOMILY 2017Canon Francis Xavier Altiere, ICKSP

A poet once said, “the end of all our exploring, will be to arrive where we started, and know the place for the first time” (Little Gidding, V). As we contemplate today the mystery of the Word-made-flesh – of God who now at last in the “fullness of time” (Galatians 4:4) takes on human nature to accomplish his plan of our salvation – I am reminded of these words as we look upon the Christ Child in his Crib. Is it not striking that Jesus Christ begins his earthly life in a borrowed cave, because there was no room at the inn, wrapped up in linen swaddling clothes, knowing in advance that 33 years later he would end his earthly life much the same way: in another borrowed cave – the tomb lent by one of his secret disciples – wrapped up this time in a linen funeral shroud? This child born between two beasts, this man crucified between two criminals: he is the same God Almighty whose earthly throne in the Jerusalem Temple perched between two cherubim. “The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib: but Israel hath not known me, and my people hath not understood” (Isaiah 1:3).

These thoughts help us, who have perhaps become too accustomed to the sentimental aspect of the Christmas story, to arrive where we started and to know the place for the first time: to come on bended knee into the Crib this year and to remember that the new-born Baby in Mary’s arms beneath the star of Bethlehem will one day lie lifeless in her arms beneath the cross. We already know how the story ends: with a death and a resurrection. Yet we come back year after year, the eternal freshness of Christmas making us forget the passing years.

What do you think we would have heard in the stable if we could have been there at that first Christmas 2000 years ago? Hush, hush, don’t wake the sleeping Redeemer, but come and lean in closely. As God sleeps in his bed of straw, I seem to hear not so much a voice as an echo: even with eyes closed, the tender Babe sees the world around him – the world he made, after all – and from within the depths of his soul he asks the question that one day he asked out loud to Peter: “and he asked his disciples, saying: … But who do you say that I am?” (St. Matthew 16:13-15). One question, so many answers!

Mary, who do you say that I am? Sweet Mother, more than anyone else you understand the true mystery of Christmas. With a mother’s love you gaze upon your baby son, but you look deeper, Mary: you see beyond the outward veil of flesh, the eternal Son of God: born eternally of the Father he now is born in time through you. You ponder the prophetic word which said, “he that made me, rested in my tabernacle” (Ecclesiasticus 24:12). O first and living ciborium, you invite us today not to the stable but to the tabernacle, that we may adore hidden under the veil of bread him whom you adored in his crib of straw. Scripture tells us: “they found the Child with Mary his mother” (St. Matthew 2:11). It will be the same for us, O holy Virgin: if we want to find Jesus, we must find him with you.

People of Bethlehem, who do you say that I am? What: an inconvenience, an unwanted child? You could at least have seen a family in need and yet in your inn there is no room. “He was in the world, and the world was made by him, and the world knew him not. He came unto his own, and his own received him not” (St. John 1:11).

Shepherds, who do you say that I am? You are simple men: the Pharisees of Jerusalem think nothing of you because you do not share their sophisticated learning. But you are men of the promise: you know only that God promised your Fathers a Redeemer and you know that he is faithful; you are not ashamed to live in the backwater of Bethlehem because you remember the prophet’s word: “And thou Bethlehem art a little one among the thousands of Juda: out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be the ruler in Israel: and his going forth is from the beginning, from the days of eternity” (Micah 5:2). The days marked out by the prophet have elapsed: now is the time for promise made to become promise fulfilled. The angel song is the reward of your humility, and you are the first ones invited to adore in the flesh the one whom even Moses feared to see in the thunders of Mount Sinai.

King Herod, who do you say that I am? O saddest of sinners, the wilfully ignorant. The scribes of Jerusalem open to you the prophetic books: the finger of the centuries points out the Messiah. Not only do you refuse to adore, but you think you can destroy God’s plan! We weep for you, poor Herod, when we see you at the head not of those who adore, but of the long line of dictators who think that they can build a human peace by refusing the Prince of Peace. The Holy Innocents, the victims of Roman persecution, those who fall to Mohammed’s sword, the hordes massacred by Communism: their blood cries out for you, Herods old and new! Your names, O persecutors, pollute the dustbin of history: but the divine Child remains on his throne and he breaks your rod of iron.

And you, what about you, my dear friends sitting here today: who do YOU say that he is? Is he just a family tradition, a little statue we cart out once a year just to put him away again in a box when we have opened our gifts and eaten our cookies? Do we feel threatened like Herod, somehow aware that if he is who he says he is, then we need to give him our whole life? Are we indifferent like the people of Bethlehem: is there no room in our inn, because it is over full with the little pet sins we don’t really want to give up? If we do not come regularly to Mass or if it has been years since our last confession, if we do not pray or if there is someone we still have never forgiven, then this year is the Christmas when we finally decide to put things right. God did not send his only Son, he did not condescend to the poverty of the stable or the shame of the cross, simply so that he could get his picture on a greeting card. He came to save us: “this day, is born to you a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord” (St. Luke 2:11). Yes, brothers, he came to save us because we need to be saved. Because he has come, salvation is now possible – but salvation is not automatic, and salvation is not for the indifferent. If you want to see him one day in heaven, then we must come to him today on bended knee with Mary and Joseph and the shepherds.

Come into the stable with me – we will wait for the shepherds to pay their humble homage – and let us see it anew as if for the first time. Today, heaven is all wrapped up in swaddling clothes. He is there waiting – waiting for you. Christmas is there to remind us that we also must decide. The world can never be the same once God enters it as one of us. It is your turn now to come to the manger. We won’t wake the sleeping Babe, but our hearts whisper our response: “I live in the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and delivered himself for me” (Galatians 2:20).

These thoughts help us, who have perhaps become too accustomed to the sentimental aspect of the Christmas story, to arrive where we started and to know the place for the first time: to come on bended knee into the Crib this year and to remember that the new-born Baby in Mary’s arms beneath the star of Bethlehem will one day lie lifeless in her arms beneath the cross. We already know how the story ends: with a death and a resurrection. Yet we come back year after year, the eternal freshness of Christmas making us forget the passing years.

What do you think we would have heard in the stable if we could have been there at that first Christmas 2000 years ago? Hush, hush, don’t wake the sleeping Redeemer, but come and lean in closely. As God sleeps in his bed of straw, I seem to hear not so much a voice as an echo: even with eyes closed, the tender Babe sees the world around him – the world he made, after all – and from within the depths of his soul he asks the question that one day he asked out loud to Peter: “and he asked his disciples, saying: … But who do you say that I am?” (St. Matthew 16:13-15). One question, so many answers!

Mary, who do you say that I am? Sweet Mother, more than anyone else you understand the true mystery of Christmas. With a mother’s love you gaze upon your baby son, but you look deeper, Mary: you see beyond the outward veil of flesh, the eternal Son of God: born eternally of the Father he now is born in time through you. You ponder the prophetic word which said, “he that made me, rested in my tabernacle” (Ecclesiasticus 24:12). O first and living ciborium, you invite us today not to the stable but to the tabernacle, that we may adore hidden under the veil of bread him whom you adored in his crib of straw. Scripture tells us: “they found the Child with Mary his mother” (St. Matthew 2:11). It will be the same for us, O holy Virgin: if we want to find Jesus, we must find him with you.

People of Bethlehem, who do you say that I am? What: an inconvenience, an unwanted child? You could at least have seen a family in need and yet in your inn there is no room. “He was in the world, and the world was made by him, and the world knew him not. He came unto his own, and his own received him not” (St. John 1:11).

Shepherds, who do you say that I am? You are simple men: the Pharisees of Jerusalem think nothing of you because you do not share their sophisticated learning. But you are men of the promise: you know only that God promised your Fathers a Redeemer and you know that he is faithful; you are not ashamed to live in the backwater of Bethlehem because you remember the prophet’s word: “And thou Bethlehem art a little one among the thousands of Juda: out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be the ruler in Israel: and his going forth is from the beginning, from the days of eternity” (Micah 5:2). The days marked out by the prophet have elapsed: now is the time for promise made to become promise fulfilled. The angel song is the reward of your humility, and you are the first ones invited to adore in the flesh the one whom even Moses feared to see in the thunders of Mount Sinai.

King Herod, who do you say that I am? O saddest of sinners, the wilfully ignorant. The scribes of Jerusalem open to you the prophetic books: the finger of the centuries points out the Messiah. Not only do you refuse to adore, but you think you can destroy God’s plan! We weep for you, poor Herod, when we see you at the head not of those who adore, but of the long line of dictators who think that they can build a human peace by refusing the Prince of Peace. The Holy Innocents, the victims of Roman persecution, those who fall to Mohammed’s sword, the hordes massacred by Communism: their blood cries out for you, Herods old and new! Your names, O persecutors, pollute the dustbin of history: but the divine Child remains on his throne and he breaks your rod of iron.

And you, what about you, my dear friends sitting here today: who do YOU say that he is? Is he just a family tradition, a little statue we cart out once a year just to put him away again in a box when we have opened our gifts and eaten our cookies? Do we feel threatened like Herod, somehow aware that if he is who he says he is, then we need to give him our whole life? Are we indifferent like the people of Bethlehem: is there no room in our inn, because it is over full with the little pet sins we don’t really want to give up? If we do not come regularly to Mass or if it has been years since our last confession, if we do not pray or if there is someone we still have never forgiven, then this year is the Christmas when we finally decide to put things right. God did not send his only Son, he did not condescend to the poverty of the stable or the shame of the cross, simply so that he could get his picture on a greeting card. He came to save us: “this day, is born to you a Saviour, who is Christ the Lord” (St. Luke 2:11). Yes, brothers, he came to save us because we need to be saved. Because he has come, salvation is now possible – but salvation is not automatic, and salvation is not for the indifferent. If you want to see him one day in heaven, then we must come to him today on bended knee with Mary and Joseph and the shepherds.

Come into the stable with me – we will wait for the shepherds to pay their humble homage – and let us see it anew as if for the first time. Today, heaven is all wrapped up in swaddling clothes. He is there waiting – waiting for you. Christmas is there to remind us that we also must decide. The world can never be the same once God enters it as one of us. It is your turn now to come to the manger. We won’t wake the sleeping Babe, but our hearts whisper our response: “I live in the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and delivered himself for me” (Galatians 2:20).

↧

What Would the Canonization of Paul VI Mean for the Liturgy and Liturgical Reform?

Many of our readers, I am sure, have seen reports to the effect that Pope Paul VI may be canonized in the coming year. It does not appear that these reports have been officially confirmed. I do not propose to say anything here about whether this would be per se appropriate or opportune; if readers wish to comment, I ask them to address only the question of what this would mean for the future prospects of the liturgy and liturgical reform.

As far as I am concerned, the short answer is: absolutely nothing.

The canonization of a Saint does not change the facts of his earthly life. It does not rectify the mistakes he may have made, whether knowingly or unknowingly. It does not change his failures into successes, whether they came about through his fault or that of others. When St Joseph Calasanz died in 1648, the religious order he had founded, the Piarists, was to all intents and purposes destroyed. Ten years after he was canonized, St Alphonse Liguori was tricked by a close friend and early collaborator into signing a document which badly compromised the Redemptorist Order, and he was openly reproved by his confreres for having destroyed it. (The life of St Joseph Calasanz was one of his favorite books for spiritual reading in his later years.) These are historical facts which were not in the least bit altered by their later canonization and the later restoration of their orders.

Likewise, there have been and still are many Catholic historians who believe that St Pius V’s excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I of England, and his decree releasing her subjects from obedience to her, was a significant error in judgment; they are not bad or disloyal Catholics for holding such an opinion. There are of course others who hold exactly the opposite opinion, and they are not good and loyal Catholics merely for the fact of holding such an opinion.

I mention St Pius V particularly because he also, of course, gave the Church a significant reform of the liturgy. If Paul VI is indeed canonized, it will surely be argued that his liturgical reform must be held in the same veneration shown to that of St Pius V in the post-Tridentine period. This will be a false comparison on every level, and should be flatly rejected as such. The Pius V reform is significant precisely because it was deliberately conceived as a very conservative reform in the proper sense of the term, a reform that sought to conserve the authentic tradition of Catholic worship, and change only what it was felt to be absolutely necessary to change. The Paul VI reform is significant for exactly the opposite reason, because it introduced more changes into the liturgy and more rapidly than had ever happened before in the Church’s history.

The reform of the liturgical books begun by St Pius V and continued by his successors was one of the great successes of the Counter Reformation, and one from which the Church unquestionably drew many spiritual benefits. This does not change the fact that, unwittingly, it also set in motion a process by which the other Uses of the Roman Rite were gradually Romanized, and many valuable things (such as nearly the entire corpus of Sequences) were effectively lost. Many liturgical writers have regretted such losses, and whether one agrees with them or not, they have not been bad Catholics for doing so. The same applies to the reform of the Breviary by St Pius X; and likewise, many Catholics hold Pope Pius XII in the highest regard for a variety of good reasons, while disliking the Holy Week reform which he promulgated.

All of this is to say, the intrinsic merits or demerits of the post-Conciliar reform, and its status as a success or a failure, will not change in any way, shape or form if Pope Paul VI is indeed canonized. No one can honestly say otherwise, and no one has the right to criticize, attack, silence or call for the silencing of other Catholics if they contest that reform. If that reform went beyond the spirit and the letter of what Vatican II asked for in Sacrosanctum Concilium, as its own creators openly bragged that it did; if it was based on bad scholarship and a significant degree of basic incompetence, leading to the many changes now known to be mistakes; if it failed utterly to bring about the flourishing of liturgical piety that the Fathers of Vatican II desired, none of these things will change if Paul VI is canonized. Just as the canonizations of Pius V and X, and the future canonization of XII, did not place their liturgical reforms beyond question or debate, the canonization of Paul VI will not put anything about his reform beyond debate, and no one has any right to say otherwise.

As far as I am concerned, the short answer is: absolutely nothing.

The canonization of a Saint does not change the facts of his earthly life. It does not rectify the mistakes he may have made, whether knowingly or unknowingly. It does not change his failures into successes, whether they came about through his fault or that of others. When St Joseph Calasanz died in 1648, the religious order he had founded, the Piarists, was to all intents and purposes destroyed. Ten years after he was canonized, St Alphonse Liguori was tricked by a close friend and early collaborator into signing a document which badly compromised the Redemptorist Order, and he was openly reproved by his confreres for having destroyed it. (The life of St Joseph Calasanz was one of his favorite books for spiritual reading in his later years.) These are historical facts which were not in the least bit altered by their later canonization and the later restoration of their orders.

Likewise, there have been and still are many Catholic historians who believe that St Pius V’s excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I of England, and his decree releasing her subjects from obedience to her, was a significant error in judgment; they are not bad or disloyal Catholics for holding such an opinion. There are of course others who hold exactly the opposite opinion, and they are not good and loyal Catholics merely for the fact of holding such an opinion.

I mention St Pius V particularly because he also, of course, gave the Church a significant reform of the liturgy. If Paul VI is indeed canonized, it will surely be argued that his liturgical reform must be held in the same veneration shown to that of St Pius V in the post-Tridentine period. This will be a false comparison on every level, and should be flatly rejected as such. The Pius V reform is significant precisely because it was deliberately conceived as a very conservative reform in the proper sense of the term, a reform that sought to conserve the authentic tradition of Catholic worship, and change only what it was felt to be absolutely necessary to change. The Paul VI reform is significant for exactly the opposite reason, because it introduced more changes into the liturgy and more rapidly than had ever happened before in the Church’s history.

The reform of the liturgical books begun by St Pius V and continued by his successors was one of the great successes of the Counter Reformation, and one from which the Church unquestionably drew many spiritual benefits. This does not change the fact that, unwittingly, it also set in motion a process by which the other Uses of the Roman Rite were gradually Romanized, and many valuable things (such as nearly the entire corpus of Sequences) were effectively lost. Many liturgical writers have regretted such losses, and whether one agrees with them or not, they have not been bad Catholics for doing so. The same applies to the reform of the Breviary by St Pius X; and likewise, many Catholics hold Pope Pius XII in the highest regard for a variety of good reasons, while disliking the Holy Week reform which he promulgated.

All of this is to say, the intrinsic merits or demerits of the post-Conciliar reform, and its status as a success or a failure, will not change in any way, shape or form if Pope Paul VI is indeed canonized. No one can honestly say otherwise, and no one has the right to criticize, attack, silence or call for the silencing of other Catholics if they contest that reform. If that reform went beyond the spirit and the letter of what Vatican II asked for in Sacrosanctum Concilium, as its own creators openly bragged that it did; if it was based on bad scholarship and a significant degree of basic incompetence, leading to the many changes now known to be mistakes; if it failed utterly to bring about the flourishing of liturgical piety that the Fathers of Vatican II desired, none of these things will change if Paul VI is canonized. Just as the canonizations of Pius V and X, and the future canonization of XII, did not place their liturgical reforms beyond question or debate, the canonization of Paul VI will not put anything about his reform beyond debate, and no one has any right to say otherwise.

↧

EF Pontifical Mass for Epiphany in Nashua, New Hampsire

The Fraternity of St Peter’s Church in Nashua, New Hampsire, St Stanislaus, will welcome His Excellency Peter Libasci, bishop of Manchester, for the celebration of a solemn Pontifical Mass in the Extraordinary Form on Saturday, January 6th, the feast of the Epiphany. The Mass will begin at 9 a.m.; the church is located at 43 Franklin Street.

↧

↧

Christmas Photopost 2017 (Part 2)

Our photopost series for Christmas continues; we have received a very large number of submissions, so once again, a reminder that if you don’t see yours here, they will be posted in the next one (or perhaps the one after that, since they are still coming in!) This set includes the Byzantine, Maronite and Ambrosian Rites, Christmas Matins in the traditional Roman, and a first ad orientem; as always, we are grateful to all those who contribute to the work of evangelizing through beauty by sharing these with our readers throughout the world. Merry Christmas!

St Peter Eastern Catholic Church - Ukiah, California

Vespers and Litia

Sacred Heart - Albany, New York

St Clement Parish - Ottawa, Ontario (FSSP)

Mother of God Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church - Conyers, Georgia

All Saints - Minneapolis, Minnesota (FSSP)

Matins of Christmas before Midnight Mass

Mater Ecclesiae - Berlin, New Jersey

Church of Our Lady’s Nativity - Legnano, Italy (Ambrosian Rite)

National Shrine of Our Lady of Lebanon - North Jackson, Ohio

Pontifical Liturgy in the Maronite Rite, celebrated by Protopresbyter Anthony Spinosa

Holy Innocents - New York City

Good Shepherd - Golden Valley, Minnesota

This was the first time Mass was celebrated in this church ad orientem on a Holy Day of obligation.

St Joseph Chapel - San Antonio, Texas

↧

Tonsure, Minor Orders and Subdiaconal Ordination in Fréjus-Toulon

We interrupt our regularly scheduled Christmas photoposts (which will resume tomorrow) to bring you some photographs from our good friends of the Fraternity of St Joseph the Guardian. On December 23rd, the Saturday Ember Day of Advent, His Excellency Dominique Rey, Bishop of Fréjus-Toulon conferred the clerical tonsure, minor orders and subdiaconate on various members of the Fraternity and of the Monastery of St Benedict. You can see the complete photosets on their Facebook page. Our congratulations to these young men, to their religious families, and to the diocese. As we end this year of grace, let us remember to thank God for all of the benefits we receive from Him through the sacred liturgy and the ministry of the priesthood, and never forget to pray for all priests and seminarians throughout the world!

The tonsure of the clerics.

Formally receiving the surplice as the liturgical vestment proper to their new state.

The mighty cantors!

Prostration at the litany of the Saints

The subdeacons synbolically receive the cruets of wine and water, the administration of which during the solemn Mass proper to their ministry.Being vested with the tunicle.

One of the newly ordained subdeacons sings the Epistle at the Mass, even though he does not then “take over” as the subdeacon of the Mass.↧

Picture of the Year 2017

As our last post of the year 2017, I would like to share with our readers once again this photo from our always popular Fostering Young Vocations series, of four boys dressed for Halloween as Saints of the Order of Preachers, Dominic, Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas and Martin de Porres.

For me, this photo, and the caption put on it by the Dominican Province of the Holy Name of Jesus, (by whose courtesy we published it in November) sums up all the good things happening in the Church today: the continual rediscovery of the life of the Faith, and the traditions that enshrine it for every new generation. As we enter the New Year, it behooves us to remember that every age in the Church’s life gives us many reasons to pray and work for reform and renewal, but also many reasons for hope and joy.

I also want to mention this photo from a recent photopost of Rorate Masses, which are decidedly one of the features of the Catholic liturgical tradition that brings out the best and most beautiful. The photographer captured this very impressive shot at the Fraternity of St Peter’s church in Baltimore, the shrine of St Alphonsus; in the upper left part, the priest in the pulpit almost looks like he’s floating in the darkness. The name of the photographer was not sent in with the picture; whoever you are, very nice work indeed!

For me, this photo, and the caption put on it by the Dominican Province of the Holy Name of Jesus, (by whose courtesy we published it in November) sums up all the good things happening in the Church today: the continual rediscovery of the life of the Faith, and the traditions that enshrine it for every new generation. As we enter the New Year, it behooves us to remember that every age in the Church’s life gives us many reasons to pray and work for reform and renewal, but also many reasons for hope and joy.

I also want to mention this photo from a recent photopost of Rorate Masses, which are decidedly one of the features of the Catholic liturgical tradition that brings out the best and most beautiful. The photographer captured this very impressive shot at the Fraternity of St Peter’s church in Baltimore, the shrine of St Alphonsus; in the upper left part, the priest in the pulpit almost looks like he’s floating in the darkness. The name of the photographer was not sent in with the picture; whoever you are, very nice work indeed!

↧

The Feast of the Circumcision 2018

He that is cut off (circumcisus) from the vices is deemed worthy of the vision of God, for the eyes of the Lord are upon the just. (Ps. 33, 16) You see that all the course of the old Law was a type of the future; for the circumcision signified the purgation of sins. But since the fragility of man’s body and mind, being yet inclined towards a certain longing to sin, is tangled up inextricably in the vices, the circumcision on the eighth day prefigures that complete cleansing from sin (which we shall have) in the age of the resurrection. This is the reason for the words, “Every male that openeth the womb shall be called holy unto the Lord.” For in these words of the Law was promised the child-birthing of the Virgin; and truly was He holy, for He was without blemish. Finally, the words repeated by the Angel declare in the same way that He is the one designated by the Law: “The Holy One that shall be born of thee, shall be called the Son of God.” (Luke 1, 35) For alone among all that are born of women was the Lord Jesus Christ holy in all ways, Who in the newness of His immaculate birth, felt no contagion from human corruption, and in His heavenly majesty drove it away. (From St Ambrose’s Commentary on the Gospel of Luke, the homily for the feast of the Circumcision in the Breviary of St Pius V.)

To all our readers, we wish a most blessed and prosperous New Year!

|

| The Circumcision of Christ, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1605 |

↧

↧

Christmas 2017 Photopost (Part 3)

We begin the new year by finishing up some business from the old one, our final set of photos of your Christmas liturgies. We will also be doing one or more photoposts for Epiphany; a reminder will be posted during the week. In the mean time, our thanks as always to all those who sent these in - Evangelize though beauty!

In the traditional Ambrosian Rite, the chasuble is lifted up perpendicular to the floor at the incensations.

Santa Maria della Consolazione - Milan, Italy (Ambrosian Rite)

It is a common custom in Italy, shared by the Ambrosian Rite, to bring a statue of the Infant Jesus into the church at the beginning of Midnight Mass, and place it in a prominent place on the altar, and incense it.

In the traditional Ambrosian Rite, the chasuble is lifted up perpendicular to the floor at the incensations.

St Matthew - Monroe, Louisiana

Cathedral of the Sacred Heart - San Angelo, Texas

Mass of the Holy Innocents; the sermon was delivered by His Exellency Michael Sis, bishop of San Angelo.

Holy Innocents - New York City

Mass of the Patronal Feast

St Margaret Mary - Oakland, California (ICK)

Immaculate Heart of Mary Oratory - San José, California (ICK)

Mount St Peter - New Kensington, Pennsylvania

St John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church - Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Tradition is for the young!

St Gianna Beretta Molla - Northfield, New Jersey

Cathedral of St Eugene - Santa Rosa, California

Pontifical Shrine of Our Lady of Mt Carmel - New York City

Sunday after Christmas

Sunday after Christmas

↧

Using Drone Warfare in the Battlefield of Sacred Music

I am wondering if the experiences of choir directors out there confirm an observation of mine about the power of a drone - that is, a note sung continuously alongside the melody - to help engage people with sacred music in the right way? I have seen the drone used in both Gregorian and Byzantine chant to powerful effect. I suggest that this is something that could be used more, especially in modern churches which are not designed with an acoustic that naturally produces a harmonic resonance. In my opinion, chant requires that faint suggestion of harmony that such a resonance lends to it, as one might hear in a Gothic abbey, for example, in order to have full effect as sacred music. (I will explain my reasons for saying this later.)

Here are my thoughts as to why this might be. One of the attributes of beauty, famously listed by St Thomas, is due proportion. When something has due proportion, each part of an object must be in right relation to each other part in a way that is appropriate to the purpose of the whole. What constitutes due proportion in any particular situation is to a degree a matter of judgment, but there are geometric and arithmetical guidelines that can inform that judgment.

Beauty, it seems, is ordered by the number three. Going all the way back to pre-Christian classical culture, it was noticed that in the human response to things in combination - that is, in relation to each other - a minimum of three things were needed to constitute some sense of completeness in the arrangement. If there are just two in combination, such combination can still be beautiful, but there is inherent within it a sense that it is incomplete.

This is most easily explained in the natural response of most people to the combinations of notes in music. When two notes are placed in a relationship to each other, it is called an interval, and when it is pleasing it is described as “consonant”, meaning literally, “sounding together.” However, it was also noticed that when people hear a harmonious interval, it still seems to lack something. If you ask the music theorist why this is, he will tell you that this happens because an interval can be the basis of either a major or a minor chord, and you don’t know which until the third note is supplied. When that third note is supplied, and a full chord is created and the sense of deficiency is removed. This suggests that we have hardwired into us such a pattern of the harmony of music.

The consensus on this differing human response to intervals and chords has never really been questioned. Even the most secular music schools of today would concur and use this as the basis for the theory of musical harmony, although they may then go on to reject consonance as a good, and promote dissonance, which literally means “not agreeing in sound.”

Because musical harmony could be described numerically, by considering, for example, the magnitudes of pipes or strings that produced the separate notes, the assumption was made that the same numerical patterns present in musical intervals and chords could be used in any aspect of time and space in order to make the culture beautiful. It is most obviously applied in architecture, in which the dimensions of buildings can correspond to them. In this 19th-century building in Annapolis, Maryland, we see traditional harmony in architecture based on the principle of three. It has three stories of different sizes; the harmony is made apparent by making the windows different sizes.

This is why we need a minimum of three objects to descript proportion - we can’t have two or more ratios unless we have that many at least. Although the language which describes these proportions (he lists 10 in all) is musical, they are not all derived from musical harmony. They come from the observation of the natural relationships that contribute to the beauty of the cosmos, the human form, and the observation of symmetries that exist within the relationships between numbers and shapes in the abstract world of arithmetic and in geometry. (Note: the Golden Section is not traditionally included among them, despite what many people today assume!)

The assumption was that instrumental music was simply one manifestation of the principle of beauty that runs through all of Creation. For the Christian, these are all facets of the divine beauty that is embodied in the person of Christ.

Now, back to sacred music. The beauty of chant comes from the patterns of intervals that exist between notes from the melodyies which, if not heard simultaneously, are close enough in time that we connect one to the other, just as we can hear a chord in an arpeggio as well as directly in harmony.

Chant is most beautiful, I always feel, when sung in a church with an acoustic that provides resonances and echoes and which faintly harmonize with it. This allows the notes to merge and overlap more, and so enhance our sense of the two together. Also, we grasp on to that faint, suggested harmony, but it always leaves us wanting more because it is not fully expressed. When done well, it creates a longing that takes our imaginations to the non-material realm, and elevates our thinking to grasp the spiritual truths communicated by word and music in combination. When I hear this effect, I always imagine also that I am detecting the ghostly appearance of angels singing with us in the heavenly liturgy. This dynamic of drawing us in through beauty and then directing our imagination to the contemplation of heavenly things is built into the stylization of sacred art as well.

Sadly, many churches today do not have this kind of acoustic, and especially with carpeting, it is hard work to sing chant; in such a situation, this dynamic which draws us in and leaves us wanting more cannot operate in the same way. One way of overcoming this, perhaps, is to add a drone. It brings sacred chant to life, in my opinion. There may be reasons for this that I don’t understand, but I present the following as a possible explanation.

Adding the drone ensures that there are always two notes in relation. As the melody moves up and down, the relationship between drone and melody constantly changes as the intervals vary. In our imaginations, therefore, we grasp for a steadily changing variety of suggested major and minor chords. For this reason, chant in which the pitch of the drone moves relatively little is perceived as musically more complex than music in which the lower note moves much more, as in, for example, parallel fifths. I should say that the drone is striking when the acoustic is good too; shag-pile carpeting is not a necessary condition for the effect to be apparent!

We can hear the drone in this example of Old Roman chant:

Byzantine chant especially comes to life with the ison. Here is the Troparion of the Resurrection, mode 5, from the Melkite Greek Catholic liturgy.

It occurs to me also that this allows for an engagement with congregations that might not otherwise be possible. There is no reason why people can’t sing the drone while the skilled cantor sings the melody. This becomes a form of music that seems less precious and distant to the uninitiated.

Where I live, we have a regular pot-luck with Vespers as a social event. We sing simple psalm tones and I deliberately choose tones that finish on the final of the mode. This final becomes the drone note for the chant. The small group, which is not composed of specialist singers, is divided into two groups, and we sing antiphonally, alternating between melody and harmonizing drone. People catch on quickly and enjoy doing it, and the effect is striking even in our living room! Furthermore, I sing collects to a slightly more complex melody, and begin by asking everybody to hum the drone note before I do so. These are not expert singers; in fact, a number are people who never sing hymns at church, but they find this easier to sing than the usual fare at their Sunday Mass.

There is an additional point in that it seems to give the music an earthy quality that will encourage all, both men and women, to sing, without compromising on the sacred quality.

Also, if I ever find myself trapped in the pews in a Mass that has missalette music I create a little chant-like micro-environment around me by trying to improvise an ison to the hymns and ditties. I aim to make it as deep and reverberating as I possibly can - we are talking Russian-basso-profundo levels of reverberation here. It seems to pull it in the right direction at least.

If you want to read more about my views on the philosophy of missalette music, incidentally, read 'Breaking Bad - Why Missalette Music Is Driving People Away from Mass, Especially the Young.'

Here are my thoughts as to why this might be. One of the attributes of beauty, famously listed by St Thomas, is due proportion. When something has due proportion, each part of an object must be in right relation to each other part in a way that is appropriate to the purpose of the whole. What constitutes due proportion in any particular situation is to a degree a matter of judgment, but there are geometric and arithmetical guidelines that can inform that judgment.

Beauty, it seems, is ordered by the number three. Going all the way back to pre-Christian classical culture, it was noticed that in the human response to things in combination - that is, in relation to each other - a minimum of three things were needed to constitute some sense of completeness in the arrangement. If there are just two in combination, such combination can still be beautiful, but there is inherent within it a sense that it is incomplete.

This is most easily explained in the natural response of most people to the combinations of notes in music. When two notes are placed in a relationship to each other, it is called an interval, and when it is pleasing it is described as “consonant”, meaning literally, “sounding together.” However, it was also noticed that when people hear a harmonious interval, it still seems to lack something. If you ask the music theorist why this is, he will tell you that this happens because an interval can be the basis of either a major or a minor chord, and you don’t know which until the third note is supplied. When that third note is supplied, and a full chord is created and the sense of deficiency is removed. This suggests that we have hardwired into us such a pattern of the harmony of music.

The consensus on this differing human response to intervals and chords has never really been questioned. Even the most secular music schools of today would concur and use this as the basis for the theory of musical harmony, although they may then go on to reject consonance as a good, and promote dissonance, which literally means “not agreeing in sound.”

Because musical harmony could be described numerically, by considering, for example, the magnitudes of pipes or strings that produced the separate notes, the assumption was made that the same numerical patterns present in musical intervals and chords could be used in any aspect of time and space in order to make the culture beautiful. It is most obviously applied in architecture, in which the dimensions of buildings can correspond to them. In this 19th-century building in Annapolis, Maryland, we see traditional harmony in architecture based on the principle of three. It has three stories of different sizes; the harmony is made apparent by making the windows different sizes.

It is possible to represent an interval in architecture as well, as in this two-storey colonial house. After all, not everyone can afford to have a three-storey house!

However, even if you can only have two storeys, there are ways to incorporate the beauty of three into the building. Here, in this nicely proportioned modern townhouse, the basement has a smaller window, but it is deliberately designed to give the impression that it extends below ground and is longer, although largely hidden. In our imaginations, we create that third element to fit the pattern and imagine the basement extending well below ground. We naturally want to see that rhythmical progression where the first relates to the second as the second relates to the third.

Generally, you see the magnitude of storeys reducing as you go up; this is perhaps analogous to the major triad. But you can have a minor triad arrangement as well in which the larger spacing is higher. In the picture below, look at the spacing of the horizontal lines that divide the spaces between the windows, and not just the window size.

Harmonious proportion was defined in Boethius’ De Institutione Arithmetica as “a consonant relationship of two or more ratios.” A ratio is a relationship between two magnitudes. Put another way, Boethius is telling us that proportion is an appealing relationship between two relationships.

This is why we need a minimum of three objects to descript proportion - we can’t have two or more ratios unless we have that many at least. Although the language which describes these proportions (he lists 10 in all) is musical, they are not all derived from musical harmony. They come from the observation of the natural relationships that contribute to the beauty of the cosmos, the human form, and the observation of symmetries that exist within the relationships between numbers and shapes in the abstract world of arithmetic and in geometry. (Note: the Golden Section is not traditionally included among them, despite what many people today assume!)

The assumption was that instrumental music was simply one manifestation of the principle of beauty that runs through all of Creation. For the Christian, these are all facets of the divine beauty that is embodied in the person of Christ.

Now, back to sacred music. The beauty of chant comes from the patterns of intervals that exist between notes from the melodyies which, if not heard simultaneously, are close enough in time that we connect one to the other, just as we can hear a chord in an arpeggio as well as directly in harmony.

Chant is most beautiful, I always feel, when sung in a church with an acoustic that provides resonances and echoes and which faintly harmonize with it. This allows the notes to merge and overlap more, and so enhance our sense of the two together. Also, we grasp on to that faint, suggested harmony, but it always leaves us wanting more because it is not fully expressed. When done well, it creates a longing that takes our imaginations to the non-material realm, and elevates our thinking to grasp the spiritual truths communicated by word and music in combination. When I hear this effect, I always imagine also that I am detecting the ghostly appearance of angels singing with us in the heavenly liturgy. This dynamic of drawing us in through beauty and then directing our imagination to the contemplation of heavenly things is built into the stylization of sacred art as well.

Sadly, many churches today do not have this kind of acoustic, and especially with carpeting, it is hard work to sing chant; in such a situation, this dynamic which draws us in and leaves us wanting more cannot operate in the same way. One way of overcoming this, perhaps, is to add a drone. It brings sacred chant to life, in my opinion. There may be reasons for this that I don’t understand, but I present the following as a possible explanation.

Adding the drone ensures that there are always two notes in relation. As the melody moves up and down, the relationship between drone and melody constantly changes as the intervals vary. In our imaginations, therefore, we grasp for a steadily changing variety of suggested major and minor chords. For this reason, chant in which the pitch of the drone moves relatively little is perceived as musically more complex than music in which the lower note moves much more, as in, for example, parallel fifths. I should say that the drone is striking when the acoustic is good too; shag-pile carpeting is not a necessary condition for the effect to be apparent!

We can hear the drone in this example of Old Roman chant:

Byzantine chant especially comes to life with the ison. Here is the Troparion of the Resurrection, mode 5, from the Melkite Greek Catholic liturgy.

It occurs to me also that this allows for an engagement with congregations that might not otherwise be possible. There is no reason why people can’t sing the drone while the skilled cantor sings the melody. This becomes a form of music that seems less precious and distant to the uninitiated.

Where I live, we have a regular pot-luck with Vespers as a social event. We sing simple psalm tones and I deliberately choose tones that finish on the final of the mode. This final becomes the drone note for the chant. The small group, which is not composed of specialist singers, is divided into two groups, and we sing antiphonally, alternating between melody and harmonizing drone. People catch on quickly and enjoy doing it, and the effect is striking even in our living room! Furthermore, I sing collects to a slightly more complex melody, and begin by asking everybody to hum the drone note before I do so. These are not expert singers; in fact, a number are people who never sing hymns at church, but they find this easier to sing than the usual fare at their Sunday Mass.

There is an additional point in that it seems to give the music an earthy quality that will encourage all, both men and women, to sing, without compromising on the sacred quality.

Also, if I ever find myself trapped in the pews in a Mass that has missalette music I create a little chant-like micro-environment around me by trying to improvise an ison to the hymns and ditties. I aim to make it as deep and reverberating as I possibly can - we are talking Russian-basso-profundo levels of reverberation here. It seems to pull it in the right direction at least.

If you want to read more about my views on the philosophy of missalette music, incidentally, read 'Breaking Bad - Why Missalette Music Is Driving People Away from Mass, Especially the Young.'

↧

NLM Quiz no. 21: What is This Object’s Function?

I suspect that this quiz will prove to be quite difficult, so I will start with two clues. 1: The object shown in the photographs below does not have a liturgical function, properly speaking, but was used by a confraternity for a religious purpose. 2: The candlesticks to either side of it are irrelevant, but the details seen somewhat more clearly in the second photograph are very relevant. (You can click on the photos to enlarge them.) Can you guess what it was used for? Please leave your answer in the combox, and feel free to add any details or explanations you think pertinent. To keep it more interesting, please leave your answer before reading the other comments. We are always happy to hear humorous explanations as well. The answer will be given on Thursday morning (EST).

↧

Time for the Soul to Absorb the Mysteries — Part 5: Concluding Reflections

Looking back over our survey of the classical rite of Mass (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4), we see that all of the elements we have considered produce the effect of a certain timelessness, of a floating in between matters of mere practicality or business. One is not checking items off of a list, but rather, ceasing to think just about getting things done; one is “setting aside all earthly cares” and letting oneself be carried along by an action that is so much vaster and deeper than oneself, a reality that shows its face only in response to our patience, attentiveness, and surrender. The more we talk, do stuff, make noise, and carry on, the less we see of that reality, the less we enter that cosmic and eternal action. When the liturgy is allowed to be itself and to do what is proper to it — slowly, repetitiously, carefully, and beautifully — we are pulled out of ourselves, our finite world and ticking time, and made to be partakers of the divine nature. This is when liturgy is a foretaste of the heavenly banquet and gives us the strength to persevere in the long pilgrimage towards it.

In fact, it would be no exaggeration to say that the Novus Ordo, in its very design and especially in its typical instantiation, stands in tension with interiority, recollection, self-awareness, and sensitivity to the divine — that keen sensus mysteriorum that is practically convertible with the traditional Roman Rite in any of its levels (Low, High, Solemn, Pontifical). The old rite, in contrast, forces us to develop habits of prayer — self-motivated prayer, since you are thrown, to a large extent, on your own resources. As a blogger once rather insightfully put it:

Let us give the last word to a priest who discovered the liturgical tradition and fell in love with it.

[1] Unfortunately this site, The Sensible Bond, was disabled, so this text is available only in cache.

[2] Online here; text slightly modified.

[3] From Dom Alcuin Reid’s review of Andrea Grillo’s Beyond Pius V.

In fact, it would be no exaggeration to say that the Novus Ordo, in its very design and especially in its typical instantiation, stands in tension with interiority, recollection, self-awareness, and sensitivity to the divine — that keen sensus mysteriorum that is practically convertible with the traditional Roman Rite in any of its levels (Low, High, Solemn, Pontifical). The old rite, in contrast, forces us to develop habits of prayer — self-motivated prayer, since you are thrown, to a large extent, on your own resources. As a blogger once rather insightfully put it:

One can still hold the new rite to be integrally Catholic, and yet consider that the culture of the extraordinary form, where the people are supposedly passive, tends to teach people to pray independently, while the culture of the ordinary form often tends to create a dynamic in which people just chat to each other in church unless they are being actively animated by a minister.[1]Fr. Chad Ripperger expands on this point:

St. Augustine said that no person can save his soul if he does not pray. Now it is a fact that mental prayer and prayer in general have collapsed among the laity (and the clergy, for that matter) in the past thirty years. It is my own impression that this development actually has to do with the ritual of the Mass. Now in the new rite, everything centers around vocal prayer, and the communal aspects of the prayer are heavily emphasized. This has led people to believe that only those forms of prayer that are vocal and communal have any real value…Fr. Ray Blake wonders aloud if the very emphasis on the spoken word has led us away from the interior spirit of worship, to such an extent that we might not be engaged in the supreme act of adoration or latria at all, but only filling the air with well-meaning verbiage, as if the church were a holy lecture hall.

The ancient ritual, on the other hand, actually fosters a prayer life. The silence during the Mass actually teaches people that they must pray. Either one will get lost in distraction during the ancient ritual or one will pray. The silence and encouragement to pray during the Mass teach people to pray on their own. While, strictly speaking, they are not praying on their own insofar as they should be joining their prayers and sacrifices to the Sacrifice and prayer of the priest, these actions are done interiorly and mentally and so naturally dispose them toward that form of prayer. This is one of the reasons that, after the Mass is said according to the ancient ritual, people are naturally quieter and tend to pray afterwards. If everything is done vocally and out loud, then once the vocal stops, people think it is over. It is very difficult to get people who attend the new rite of Mass to make a proper thanksgiving by praying afterward because their appetites and faculties have habituated them toward talking out loud.

True worship leads us to contemplate the God who is always beyond us, the God before whom Old Testament patriarchs and prophets fall on their faces in worship. Practically at every Mass I have celebrated over the thirty years I have been ordained I have felt the need “to break the bread of the word,” to preach — except at the Traditional Mass, where all I want to do is adore the Father through the Son, in the unity of the Holy Spirit. I am beginning to believe that if the Word of God does not lead us to the act of worship, there is something wrong in its presentation, and if the Mass does not lead us to fall on our knees to be fed by God, there is something wrong here, too. Contemplating the Mystery of the Trinity should lead us to be lost in the immensity and beauty of God, realising His greatness and our nothingness, desiring only to abandon ourselves to Him, crying out with Christ: “Father, into your hands I commend my Spirit.” If this realisation is not the result of worship, perhaps we are not worshipping at all![2]Joseph Shaw contrasts the scripted, regimented participation of the new Mass with the freer “open worship” characteristic of the old liturgy, which generates a peculiar sense of togetherness by the intensity of each individual worshiping the same mystery, each in his own way:

What is quite out of the question, in this kind of liturgy [viz., the Novus Ordo], is that you should engage with it at your own pace, on your own level, in prayer. Prayerful contemplation is simply not allowed: it will be interrupted within a few minutes, and you’ll get funny looks. The opposite is the case with the Traditional Mass. You are, essentially, left alone, but left alone united with the community in the act of worship. You may have things given to you to help you follow the Mass, there may even be responses (especially at a sung Mass), but no one will think you odd if you just look at what is happening on the altar in prayerful silence. And for the Canon, that is what everyone is doing. You are drawn in: it may be to something unfamiliar, if contemplative prayer is unfamiliar, but it is something which you can do your own way. It is not a Procrustean bed; you can make of it what you will.Thus, ironically, considering that the Catholic liturgy was practically turned upside-down and inside-out to promote “active participation,” the faithful who attend the old Mass today evince a superior personal engagement in what they are doing. Why is this the case? Dom Alcuin Reid suggests two reasons: first, that people who are drawn to traditional worship must make significant sacrifices to find it and have often invested seriously in forming their own understanding. But there is a second reason having to do with the rites themselves:

Perhaps also it is due to the very demands they place on the worshipper — one has to find ways of connecting with these rites, or indeed of allowing them to connect with us, because of their ritual complexity. Their multivalent nature has a particular value: it provides varying means of connection with Christ acting in the liturgy that perhaps better correspond to our differing temperaments and psyches.[3]In my book Noble Beauty, Transcendent Holiness, I talk about the effort involved in carrying out a traditional Tenebrae service at Wyoming Catholic College, and how many hours of practice and years of iteration it has required to reach the stage we are now at: “The best and deepest things take time to assimilate, to understand, to perfect. When it comes to liturgy in particular, we have to fight tooth and nail against the modern spirit of immediate gratification and quick results” (p. 185). Nowadays, prayer and liturgical services are prone to being shortened (perhaps “short-circuited” would be a better term), since the participants are either in a hurry to get to other business, or their span of attention is just too short. For Holy Week, the very highpoint of the Church’s year, one may observe in many places that the customary procession of palms on Palm Sunday is omitted and the blessing is done after communion instead; the Reproaches on Good Friday are skipped, in spite of their immense antiquity, beauty, and spiritual power. The Novus Ordo liturgical books are characterized by the option of shortened versions of readings and prayers. The modern impatience with anything not immediately gratifying extends even to pious/liturgical activities. To this mentality, St. Josemaría Escrivá already replied, years before it reached its peak: “‘The Mass is long,’ you say, and I add: ‘Because your love is short’” (The Way, n. 529).

Let us give the last word to a priest who discovered the liturgical tradition and fell in love with it.

When you truly love God, you are not miserly in sharing your time with Him in prayer, in the Holy Mass, and other liturgical exercises, since He is constantly sharing His time with you, His beloved. Since youth, I had been accustomed to the Vatican II revisions of the liturgy. Thank God, through dear Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s Summorum Pontificum, I came to discover the solemn beauty of the traditional Latin Mass and other Catholic practices. Yes, these are more demanding of our time, but if one allows them time to penetrate the depth of the soul, one will exclaim joyfully: “Lord, it is good for us to be here.”NOTES

[1] Unfortunately this site, The Sensible Bond, was disabled, so this text is available only in cache.

[2] Online here; text slightly modified.

[3] From Dom Alcuin Reid’s review of Andrea Grillo’s Beyond Pius V.

↧

↧