This coming Sunday, the feast of the Transfiguration, His Excellency James Massa, Auxiliary Bishop of the diocese of Brooklyn, will celebrate a Pontifical Mass in the traditional rite at the church of the Holy Name, located at 245 Prospect Park West. The Mass will begin at 5 pm. (Readers may remember that Holy Name Church was beautifully un-wreckovated, as we reported in January of 2017.)

Pontifical Mass for the Transfiguration in Brooklyn

↧

↧

Catching Up With the Artists in the Sacristy Again

In January, we published several photos sent in by Fr Jeffrey Keyes, who serves as chaplain to the Marian Sisters of Santa Rosa at the Regina Pacis Convent in Santa Rosa, California. They show a nice thing which their sacristans often do when laying out the vestments for Mass, namely, making designs out of the ties of the amice, most of which refer in some way to the feast or liturgical season. Just a little thing, but, as Father wrote on his blog, “the essence of the Liturgy is Sacred, Universal and Beautiful,” and every beautiful thing, however small (and in this case, temporary) contributes to an atmosphere of prayer and reverence. The post was extremely popular, as were the follow-ups in February and April, and since you seem to really like them, here are several more from the last few months. This one from Friday of Easter week is particularly impressive.

This morning, a Votive Mass of the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary, for the sisters retreat day.

Yesterday, the Franciscan feast of Our Lady of the Angels, the church of the Portiuncula.

St Elizabeth of Portugal

Mary Help of Christians

St Damien of Molokai

A miter and crook for Ss Philip and James

St Joseph the Work - “S.J.” and a carpenter’s hammer

St Louis de Montfort

Ave

Joy

Fr Keyes with His Eminence Cardinal Burke and four of the sisters at the recent liturgical conference in Portland, Oregon.↧

On the Bishop’s Sung Mass and the Recent PCED Decree

We recently published notice of a clarification issued by the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei, to the effect that the so-called Pontifical Sung Mass, i.e., Mass sung by a bishop without the full ceremonies of the Pontifical Solemn Mass, and without assistant priest, deacon and subdeacon, does not exist according to the liturgical books of the Extraordinary Form currently in use. This was met with some negative reactions in the Disqus combox and on our Facebook page, and so I make bold to offer some thoughts on what this clarification really means and entails.

The Pontifical Sung Mass was created by the decree Inter Oecumenici, which was issued on September 26, 1964, and became legally active on March 7 of the following year. The decree simply states that “It is allowed, when necessary, for bishops to celebrate a sung Mass following the form used by priests.” It says nothing at all as to whether the bishop should retain any of the ceremonies of the Pontifical or Prelatitial Mass, and if so, which ones. Ad litteram, since none are stated, they should all be omitted. This is a change without precedent in the history Roman Rite; it has never been licit for a prelate to celebrate Mass with no indication of his rank.

This rubrical gap was the first sign of an emerging carelessness and chaos in regard to the liturgy which was also hitherto unknown. The Church had previously been extremely prudent and precise in guaranteeing that the rites of the Holy Mass properly reflect Her theological understanding of the Mass and the priesthood, and all the more so in regard to the Mass of a bishop. It is completely inappropriate for a bishop to simply pretend to not be a bishop when exercising the fullness of the priesthood vested in him as a successor of the Apostles. This was recognized by the post-Conciliar reform itself, in which this change was walked back.

I recall someone telling me once that different forms of the Pontifical Mass existed in the Middle Ages, and that they were often simpler than the Roman Pontifical Mass of the Tridentine liturgical books. I see no problem with someone doing a serious study of how they were done, if indeed sufficient documentation exists to make such as study possible, and reviving them for cases where it is genuinely impossible to put together a proper solemn Pontifical. We may make the analogy with something which was done by the Cistercians in the 1930s, when they successfully revived a medieval form of solemn Mass without a subdeacon, sometimes known as a Missa diaconalis. (This practice was also permitted by Inter oecumenici.)

For reference, here is a link to set of rubrics put together by the SSPX for a bishop’s sung Mass, importing into it the use of the miter, crozier, pectoral cross and skull cap, the ewer and basin, and a variety of the ceremonies of the Solemn Pontifical Mass, e.g. putting the maniple on before saying “Indulgentiam.” For the most part, these provisions seem to me fairly reasonable, regardless of their liceity, and certainly more appropriate than a bishop celebrating “in the manner of a priest.”

http://acss.sspxusa.org/rubrics/highmass/HighMass-Offered-by-Bishop.pdf

(I cannot help but note in passing that these rubrics begin by saying that a bishop’s Missa cantata“is allowed”, without citing who allowed it or when. As one of my Latin teachers was fond of pointing out, the word or words immediately after the opening words of a Papal document are often extremely significant, as in “Gaudium et spes, luctus et angor - The joy and hope, the mourning and anguish.” In this case, the significant third word is “Concilii”, as in “Among the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council’s primary achievements must be counted the Constitution on the Liturgy…”)

The problem, as I see it, therefore lies not in the concept of the Pontifical Sung Mass per se, but in the specific formulation of it, or rather, the completely lack thereof, given by Inter oecumenici.

Some readers have commented that their local bishops had been celebrating a Missa cantata for their communities, which they will now perhaps either cancel or reduce to a low Mass. This is certainly to be regretted, as the preferable option would be to arrange for a Pontifical Solemn Mass. (For example, Bishop Robert Morlino of Madison, Wisconsin, has celebrated quite a number of Solemn Pontifical Masses in recent years.) However, the alternative is at the very least problematic, namely, the celebration of Mass according to a form which does not exist, and therefore can only take place in a rubrical vacuum.

The Pontifical Sung Mass was created by the decree Inter Oecumenici, which was issued on September 26, 1964, and became legally active on March 7 of the following year. The decree simply states that “It is allowed, when necessary, for bishops to celebrate a sung Mass following the form used by priests.” It says nothing at all as to whether the bishop should retain any of the ceremonies of the Pontifical or Prelatitial Mass, and if so, which ones. Ad litteram, since none are stated, they should all be omitted. This is a change without precedent in the history Roman Rite; it has never been licit for a prelate to celebrate Mass with no indication of his rank.

This rubrical gap was the first sign of an emerging carelessness and chaos in regard to the liturgy which was also hitherto unknown. The Church had previously been extremely prudent and precise in guaranteeing that the rites of the Holy Mass properly reflect Her theological understanding of the Mass and the priesthood, and all the more so in regard to the Mass of a bishop. It is completely inappropriate for a bishop to simply pretend to not be a bishop when exercising the fullness of the priesthood vested in him as a successor of the Apostles. This was recognized by the post-Conciliar reform itself, in which this change was walked back.

I recall someone telling me once that different forms of the Pontifical Mass existed in the Middle Ages, and that they were often simpler than the Roman Pontifical Mass of the Tridentine liturgical books. I see no problem with someone doing a serious study of how they were done, if indeed sufficient documentation exists to make such as study possible, and reviving them for cases where it is genuinely impossible to put together a proper solemn Pontifical. We may make the analogy with something which was done by the Cistercians in the 1930s, when they successfully revived a medieval form of solemn Mass without a subdeacon, sometimes known as a Missa diaconalis. (This practice was also permitted by Inter oecumenici.)

For reference, here is a link to set of rubrics put together by the SSPX for a bishop’s sung Mass, importing into it the use of the miter, crozier, pectoral cross and skull cap, the ewer and basin, and a variety of the ceremonies of the Solemn Pontifical Mass, e.g. putting the maniple on before saying “Indulgentiam.” For the most part, these provisions seem to me fairly reasonable, regardless of their liceity, and certainly more appropriate than a bishop celebrating “in the manner of a priest.”

http://acss.sspxusa.org/rubrics/highmass/HighMass-Offered-by-Bishop.pdf

(I cannot help but note in passing that these rubrics begin by saying that a bishop’s Missa cantata“is allowed”, without citing who allowed it or when. As one of my Latin teachers was fond of pointing out, the word or words immediately after the opening words of a Papal document are often extremely significant, as in “Gaudium et spes, luctus et angor - The joy and hope, the mourning and anguish.” In this case, the significant third word is “Concilii”, as in “Among the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council’s primary achievements must be counted the Constitution on the Liturgy…”)

The problem, as I see it, therefore lies not in the concept of the Pontifical Sung Mass per se, but in the specific formulation of it, or rather, the completely lack thereof, given by Inter oecumenici.

Some readers have commented that their local bishops had been celebrating a Missa cantata for their communities, which they will now perhaps either cancel or reduce to a low Mass. This is certainly to be regretted, as the preferable option would be to arrange for a Pontifical Solemn Mass. (For example, Bishop Robert Morlino of Madison, Wisconsin, has celebrated quite a number of Solemn Pontifical Masses in recent years.) However, the alternative is at the very least problematic, namely, the celebration of Mass according to a form which does not exist, and therefore can only take place in a rubrical vacuum.

↧

A Relic of St Peter’s Chains in Vermont

Our thanks to reader Raymond Trainque for this sending in, following up on our post three days ago on the Chains of St Peter.

![]()

The diocese of Burlington, Vermont not only has a full-size facsimile of the chains displayed at St. Peter’s ad Vincula (which itself is a third-class relic, since each link was touched to the corresponding link of the original), but also has in its archives one of the actual links which bound the first Pope. Both of these holy objects were obtained through the boldness of Bishop Louis de Goesbriand (first bishop of Burlington) and the solicitude of Pope Leo XIII.

Stopping in Rome on his way to Jerusalem in 1893, de Goesbriand venerated the relics at St. Peter’s and was so struck by them that he sought and obtained permission to have a facsimile made as described above for his diocese. Discovering that seven links of the same chain were kept and seemingly nearly forgotten at St Cecilia’s in Rome, he went about obtaining one of these authentic relics. First beseeching Leo XIII in an audience before departing for the Holy Land, de Goesbriand was told that he would have a decision upon his return from the pilgrimage. Once again meeting with the Pope before setting off for Vermont, permission was granted, and one of the links was taken off and placed in a reliquary for him to take home.

On occasion, this precious relic is taken from the archives for public veneration by the faithful. This past August 1, the newly-established St. Philip Neri Latin Mass Chaplaincy (https://www.facebook.com/VermontTraditionalLatinMass/) was blessed to be able to provide one such opportunity in honor of the feast of St Peter in Chains. The relic was on the altar for a Missa Cantata and was made available for veneration by those in attendance. Of special note, our torchbearers for this Mass were two of our diocesan seminarians, with another assisting from the pews and at least two others who would have gladly joined us had circumstances allowed.

Stopping in Rome on his way to Jerusalem in 1893, de Goesbriand venerated the relics at St. Peter’s and was so struck by them that he sought and obtained permission to have a facsimile made as described above for his diocese. Discovering that seven links of the same chain were kept and seemingly nearly forgotten at St Cecilia’s in Rome, he went about obtaining one of these authentic relics. First beseeching Leo XIII in an audience before departing for the Holy Land, de Goesbriand was told that he would have a decision upon his return from the pilgrimage. Once again meeting with the Pope before setting off for Vermont, permission was granted, and one of the links was taken off and placed in a reliquary for him to take home.

On occasion, this precious relic is taken from the archives for public veneration by the faithful. This past August 1, the newly-established St. Philip Neri Latin Mass Chaplaincy (https://www.facebook.com/VermontTraditionalLatinMass/) was blessed to be able to provide one such opportunity in honor of the feast of St Peter in Chains. The relic was on the altar for a Missa Cantata and was made available for veneration by those in attendance. Of special note, our torchbearers for this Mass were two of our diocesan seminarians, with another assisting from the pews and at least two others who would have gladly joined us had circumstances allowed.

↧

Dominican Rite Solemn Mass, Sunday, August 6, Portland OR

| Solemn Dominican Mass at Holy Rosary |

The music will be provided by Cantores in Ecclesiaunder the direction of Blake Applegate, who will sing the proper chants from the Dominican Gradual.

Holy Rosary is located at 375 NE Clackamas St, Portland, OR 97232, and there is ample parking. A reception will follow the Mass in Siena Hall. We will return to the usual Missa Cantata at 11 am on Sunday August 12.

REMINDER: There will also be a Solemn Mass tonight (August 4, 7 pm) at Holy Rosary to celebrate the traditional feast of St. Dominic, the Founder of the Dominican Order.

↧

↧

The Second Vatican Council and the Lectionary—Part 2: The Preparatory Period (1960-1962)

Note: This is the second part of a three-part series. Part one, on the antepreparatory period, can be found here, and part three will look at the first and second sessions of the Council itself (1962-1963).

![]()

On June 5, 1960 (Pentecost Sunday), Pope John XXIII issued the motu proprio Superno Dei nutu, which closed the antepreparatory period and initiated the preparatory period of the Second Vatican Council. The day afterwards, June 6, he established the preparatory Commission on the Liturgy, one of ten commissions and two secretariats under the umbrella of the Central Preparatory Commission (hereafter CPC). Gaetano Cardinal Cicognani was named President of the Liturgy Commission (after his death in February 1962, Arcadio Cardinal Larraona would succeed him), with Fr Annibale Bugnini named as Secretary. [1] The Commission began its work in November 1960, with the draft schema on the liturgy being mostly completed by January 1962.

The discussions of the CPC on all the draft schemata can be found in Volume II of the praeparatoria volumes of the Acta et Documenta Concilio Oecumenico Vaticano II Apparando, some of which have been made freely available here at NLM. [2] The texts of all the draft schemata can be found in Volume III of the same series. [3] Meetings of the Liturgy Commission were held in November 1960, April 1961 and January 1962, with the draft liturgy schema being discussed by the CPC in its fifth meeting (26th March - 3 April 1962). [4]

The question of lectionary reform in the draft schema was the responsibility of the second subcommission (De Missa) of the preparatory Commission on the Liturgy. Josef Jungmann, S.J., was the relator (i.e. the one who reported back to the Liturgy Commission), with Theodor Schnitzler as secretary, and the following as consultors: Henri Jenny, Antoine Chavasse, Pietro Borella, Pierre-Marie Gy, O.P., Heinrich Kahlefeld, C.O., and Vincent Kennedy, C.S.B. It should perhaps be noted that, while Bugnini is at pains in his memoir to declare that “every part of the world in which the liturgical movement was active and prospering had to be represented on the commission, and this in a real and not a fictitious way” [5], the De Missa subcommission was very Eurocentric and heavily skewed towards German and French speakers. For the lectionary, this is quite important, as the majority of the (quite radical) proposals for reform in this area had been coming from German-speaking scholars throughout the 1950s. [6]

What is said about the lectionary in these draft schemata? Let us compare paragraph 46 of the first draft schema (discussed in April 1961) with what would become paragraph 51 of Sacrosanctum Concilium:

Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy, Subcommission II: Proposed Order of Readings (PDF)

Kahlefeld’s proposal is made up of four columns, corresponding to the readings proposed for Sundays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. This arrangement would be Year A. The four year cycle works by changing the days of the columns, so in Year B, the second column becomes the Sunday column and the first column becomes the Saturday column, and so forth. The majority of the Missale Romanum Gospel pericopes are kept in their places in Year A, (though many of the Epistle readings have been changed), and the proposal for weekday readings on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays is consonant with earlier, pre-Tridentine Roman liturgical books.

By August 1961, the draft text of paragraph 46 had been slimmed down somewhat to the following:

Finally, what did the CPC have to say about the proposals vis-à-vis the lectionary? In actual fact, not a huge amount. Francis Cardinal Spellman said that, in his view, the principle of amplifying the readings of the lectionary was impossible to argue with [12], and Julius Cardinal Döpfner called the same principle “necessary” [13], whereas André-Damien-Ferdinand Cardinal Jullien was concerned that the celebration of Mass not be made longer under false historical pretexts, because temporis praesentis condiciones omnino requirunt caeremoniarum brevitatem [14]. Given this lack of comment, and that no more changes were made to the paragraph, it appears that the CPC had little issue with the principles in it - even though, as we have seen above, those principles could be (and had already been) applied in a number of different ways.

In the final part of this series, we will examine the first and second sessions of Vatican II, and what the Council Fathers had to say about the text of what would ultimately become Sacrosanctum Concilium 51.

Notes

[1] Bugnini’s account of the meetings of the preparatory commission on the liturgy can be found in chapter 2 (PDF) of his book The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975 (Liturgical Press, 1990), pp. 14-28.

[2] The praeparatoria volumes of the Acta et Documenta will be referred to in this article by the abbreviation ADP.

[3] The text of the draft schema on the liturgy can be found in ADP III.2, pp. 7-68. Another vital resource for the study of the preparatory Commission on the Liturgy is Angelo Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II ». Documenti, Testi, Verbali (Rome: Centro Liturgico Vincenziano, 2013). In this book, Lameri reproduces the minutes of the various subcommissions which drafted the different sections of the liturgy schema, and also parallels the three different versions of the draft schema.

[4] Cf. ADP II.3, pp. 26-144 (chapters 1-2), 275-368 (chapters 3-5), 460-492 (chapters 6-8). Other relevant material includes the relatio given by Cardinal Cicognani at the first meeting (12-20 June 1961) of the CPC, updating it on the work done by the liturgy commission up to that point (cf. ADP II.1, pp. 144-147), and the discussion on the use of vernacular languages in the liturgy at the third meeting (15-23 Jan 1962) of the CPC (cf. ADP II.2, pp. 248-258).

[5] Cf. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, pp. 14-15.

[6] E.g. Heinz Schürmann, “Eine Dreijährige Perikopenordnung für Sonn- und Festtage”, Liturgisches Jahrbuch 2 (1952), 58-72; Heinrich Kahlefeld, “Ordo Lectionum Missae”, Liturgisches Jahrbuch 3 (1953), 54-59, 301-309. (My English translation of Schürmann’s article can be found here.)

[7] Cf. Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II », p. 232. The English translation of paragraph 46 of the draft is mine; I have tried to stay as close as possible to the Vatican’s English translation of SC 51 in order to make comparisons easier.

[8] Cf. Michael Magee, “The Reform of the Lectionary of the Roman Missal: Evaluations and Prospects”, in Joseph Briody (ed.), Verbum Domini: Liturgy and Scripture. Proceedings of the Ninth Fota International Liturgical Conference, 2016 (Smenos Publications, 2017), pp. 243-244. On this subject, see also Gregory DiPippo’s NLM article Sacrosanctum Concilium and the New Lectionary (11 December 2013).

[9] Cf. Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II », pp. 107-108.

[10] Cf. ADP II.3, p. 114.

[11] P.-M. Gy, for example, appeared very keen on adding an OT reading (cf. Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II », p. 107), and when H. Jenny asked about it at the January 1962 meeting of the preparatory Liturgy Commission, Bugnini replied “si parli in modo generico, lasciando alla Commissione postconciliare [speak in a generic way, leave it to the post-conciliar Commission]” (Lameri, ibid, p. 448). Cardinal Larraona’s words retento hodierno duarum lectionum numero are not exactly generic!

[12] Cf. ADP II.3, p. 117.

[13] Cf. ADP II.3, p. 123.

[14] Cf. ADP II.3, pp. 139-140.

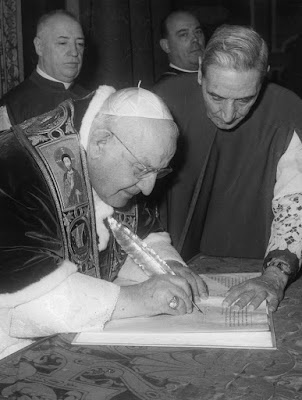

The discussions of the CPC on all the draft schemata can be found in Volume II of the praeparatoria volumes of the Acta et Documenta Concilio Oecumenico Vaticano II Apparando, some of which have been made freely available here at NLM. [2] The texts of all the draft schemata can be found in Volume III of the same series. [3] Meetings of the Liturgy Commission were held in November 1960, April 1961 and January 1962, with the draft liturgy schema being discussed by the CPC in its fifth meeting (26th March - 3 April 1962). [4]

|

Pope John XXIII signing the apostolic constitution Humanae salutis (25 Dec 1961), solemnly convoking the Second Vatican Council. |

What is said about the lectionary in these draft schemata? Let us compare paragraph 46 of the first draft schema (discussed in April 1961) with what would become paragraph 51 of Sacrosanctum Concilium:

46. Ut Fidelibus cum Mensa eucharistica etiam Mensa verbi Dei paretur et praedicatoribus maior copia Sacrae Scripturae praesto sit, thesauri biblici largius aperiantur, ita ut decursu quattuor circiter annorum maior et praestantior pars Scripturarum Sanctarum populo praelegatur. [7]

[46. In order that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God's word together with the eucharistic table and, to preachers, a greater abundance of Sacred Scripture may be before them, the treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that a greater and more representative portion of the holy scriptures will be read before the people through about four years.]

51. Quo ditior mensa verbi Dei paretur fidelibus, thesauri biblici largius aperiantur, ita ut, intra praestitutum annorum spatium, praestantior pars Scripturarum Sanctarum populo legatur.

[51. The treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God's word. In this way a more representative portion of the holy scriptures will be read to the people in the course of a prescribed number of years.]A number of things are obvious. The paragraph in the first draft is longer and more detailed; part of the rationale for lectionary reform is to benefit preachers by giving them more material to preach on. The later conciliar text praestantior pars is ambiguous, as the various vernacular translations of this phrase demonstrate; it can be translated as referring to the quantity of texts (as per the Italian la maggior parte), or the quality of texts (as per the German die wichtigsten Parte). [8] However, the first draft has both the quantity and quality in mind. Lastly, with regard to the quantity, it is noteworthy that a four year cycle of readings is explicitly mentioned in this draft. Indeed, in his capacity as relator, Jungmann did submit an example of such a cycle (designed by Kahlefeld) to the preparatory Liturgy Commission:

Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy, Subcommission II: Proposed Order of Readings (PDF)

Kahlefeld’s proposal is made up of four columns, corresponding to the readings proposed for Sundays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays. This arrangement would be Year A. The four year cycle works by changing the days of the columns, so in Year B, the second column becomes the Sunday column and the first column becomes the Saturday column, and so forth. The majority of the Missale Romanum Gospel pericopes are kept in their places in Year A, (though many of the Epistle readings have been changed), and the proposal for weekday readings on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays is consonant with earlier, pre-Tridentine Roman liturgical books.

By August 1961, the draft text of paragraph 46 had been slimmed down somewhat to the following:

46. Ut Fidelibus cum Mensa eucharistica etiam mensa verbi Dei ditior paretur, thesauri biblici largius aperiantur, ita ut decursu plurium annorum, praestantior pars Scripturarum Sanctarum populo praeleguntur.

[In order that a richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God’s word together with the eucharistic table, the treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that a more representative part of the sacred Scriptures will be read before the people through the running of more years.]Notwithstanding a couple of transpositions of words, this would be the form in which this paragraph (later numbered 38 as a result of significant alterations in the first chapter of the draft schema) would be presented to the CPC. The text et praedicatoribus maior copia Sacrae Scripturae praesto sit has been deleted, as has the word maior before praestantior (thereby introducing the previously mentioned ambiguity). Perhaps most notably, though, is that a specific number of annorum is no longer mentioned in the schema. The majority vote of the preparatory Commission on the Liturgy was that the precise number of years was something that should be considered either by the Council itself or by the post-Conciliar commission that would inevitably be set up afterwards in order to carry out liturgical reform (though the majority of members favoured a three or four year cycle). [9] This did not prevent the Liturgy Commission from making its own suggestions to the CPC anyway, as Cardinal Larraona did in his relatio at its fifth meeting:

a) In Proprio de tempore, retento hodierno duarum lectionum numero, id est, epistola et evangelium: 1) novae lectiones pro feriis infra hebdomadam, pro tribus feriis, ad minus, ponantur; 2) hae lectiones in dominica resumerentur sequentibus annis; 3) hoc pacto haberetur systema lectionum pro tribus annis; in hoc sensu schemata iam fuerunt publicata.

b) In Communi Sanctorum: in unoquoque Communi addantur lectiones pro quinque, sex vel septem diebus, ita modo ut lectiones de Communi ne repetantur intra unum vel duos menses. [10]

[a) In the Proper of Time, today’s number of two readings is to be retained, that is, epistle and gospel: 1) new readings for ferias during the week, may be established; 2) these readings may be resumed on Sundays in following years; 3) in this manner, a system of readings for three years may be kept; a draft has already been published with this sense.The broad brush strokes of Larraona’s proposals are very similar to that of Kahlefeld above. He does, however, go against the majority of the preparatory Liturgy Commission in appearing to rule out adding a third reading from the Old Testament on Sundays. [11]

b) In the Common of Saints: in each of the Commons may be added readings for five, six or seven days, thus meaning that readings from the Commons are not repeated within one or two months.]

Finally, what did the CPC have to say about the proposals vis-à-vis the lectionary? In actual fact, not a huge amount. Francis Cardinal Spellman said that, in his view, the principle of amplifying the readings of the lectionary was impossible to argue with [12], and Julius Cardinal Döpfner called the same principle “necessary” [13], whereas André-Damien-Ferdinand Cardinal Jullien was concerned that the celebration of Mass not be made longer under false historical pretexts, because temporis praesentis condiciones omnino requirunt caeremoniarum brevitatem [14]. Given this lack of comment, and that no more changes were made to the paragraph, it appears that the CPC had little issue with the principles in it - even though, as we have seen above, those principles could be (and had already been) applied in a number of different ways.

In the final part of this series, we will examine the first and second sessions of Vatican II, and what the Council Fathers had to say about the text of what would ultimately become Sacrosanctum Concilium 51.

Notes

[1] Bugnini’s account of the meetings of the preparatory commission on the liturgy can be found in chapter 2 (PDF) of his book The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975 (Liturgical Press, 1990), pp. 14-28.

[2] The praeparatoria volumes of the Acta et Documenta will be referred to in this article by the abbreviation ADP.

[3] The text of the draft schema on the liturgy can be found in ADP III.2, pp. 7-68. Another vital resource for the study of the preparatory Commission on the Liturgy is Angelo Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II ». Documenti, Testi, Verbali (Rome: Centro Liturgico Vincenziano, 2013). In this book, Lameri reproduces the minutes of the various subcommissions which drafted the different sections of the liturgy schema, and also parallels the three different versions of the draft schema.

[4] Cf. ADP II.3, pp. 26-144 (chapters 1-2), 275-368 (chapters 3-5), 460-492 (chapters 6-8). Other relevant material includes the relatio given by Cardinal Cicognani at the first meeting (12-20 June 1961) of the CPC, updating it on the work done by the liturgy commission up to that point (cf. ADP II.1, pp. 144-147), and the discussion on the use of vernacular languages in the liturgy at the third meeting (15-23 Jan 1962) of the CPC (cf. ADP II.2, pp. 248-258).

[5] Cf. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, pp. 14-15.

[6] E.g. Heinz Schürmann, “Eine Dreijährige Perikopenordnung für Sonn- und Festtage”, Liturgisches Jahrbuch 2 (1952), 58-72; Heinrich Kahlefeld, “Ordo Lectionum Missae”, Liturgisches Jahrbuch 3 (1953), 54-59, 301-309. (My English translation of Schürmann’s article can be found here.)

[7] Cf. Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II », p. 232. The English translation of paragraph 46 of the draft is mine; I have tried to stay as close as possible to the Vatican’s English translation of SC 51 in order to make comparisons easier.

[8] Cf. Michael Magee, “The Reform of the Lectionary of the Roman Missal: Evaluations and Prospects”, in Joseph Briody (ed.), Verbum Domini: Liturgy and Scripture. Proceedings of the Ninth Fota International Liturgical Conference, 2016 (Smenos Publications, 2017), pp. 243-244. On this subject, see also Gregory DiPippo’s NLM article Sacrosanctum Concilium and the New Lectionary (11 December 2013).

[9] Cf. Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II », pp. 107-108.

[10] Cf. ADP II.3, p. 114.

[11] P.-M. Gy, for example, appeared very keen on adding an OT reading (cf. Lameri, La « Pontificia Commissio de sacra liturgia praeparatoria Concilii Vaticani II », p. 107), and when H. Jenny asked about it at the January 1962 meeting of the preparatory Liturgy Commission, Bugnini replied “si parli in modo generico, lasciando alla Commissione postconciliare [speak in a generic way, leave it to the post-conciliar Commission]” (Lameri, ibid, p. 448). Cardinal Larraona’s words retento hodierno duarum lectionum numero are not exactly generic!

[12] Cf. ADP II.3, p. 117.

[13] Cf. ADP II.3, p. 123.

[14] Cf. ADP II.3, pp. 139-140.

↧

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Tirano in Lombardy

In the common Office for feasts of the Virgin Mary, the 7th antiphon of Matins reads “Rejoice, o Virgin, thou alone hast detroyed all heresies thoughout the world.” Likewise, in the common homily (which is read today for the feast of Our Lady of the Snows), St Bede says the following of the woman who spoke to Christ from the crowd, “Blessed is the womb that bore thee, and the paps that gave thee suck.”: “This woman knows His Incarnation with such integrity, and confesses it with such bravery, that she confounds both the falsehood of the great men who are present, and the faithlessness of the heretics yet to come.”

A sanctuary in the Valtellina, a valley in the northern part of the Italian region of Lombardy, is a beautiful example of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s providential intervention to preserve the integrity of the Catholic faith. In 1504, She appeared to a local man, the Blessed Mario Omodei, and asked that a shrine be built to her in the region; the apparition’s authenticity was confirmed by the miraculous healing of his very ill brother, and the end of a plague among the local animals. The foundation was laid on the feast of the Annunciation the following year, and the church was completed over the following eight years. In the meantime, however, the Valtellina had been occupied in 1512 by the bordering Swiss canton of Grisons, which would shortly turn Protestant; this occupation would last until 1797. In those years, the sanctuary proved an important bulwark against the Lutheran and allied heresies, in a region where the large Catholic majority found itself governed by an often hostile Protestant regime. Thanks to our Ambrosian correspondent Nicola de’ Grandi for these pictures.

A sanctuary in the Valtellina, a valley in the northern part of the Italian region of Lombardy, is a beautiful example of the Blessed Virgin Mary’s providential intervention to preserve the integrity of the Catholic faith. In 1504, She appeared to a local man, the Blessed Mario Omodei, and asked that a shrine be built to her in the region; the apparition’s authenticity was confirmed by the miraculous healing of his very ill brother, and the end of a plague among the local animals. The foundation was laid on the feast of the Annunciation the following year, and the church was completed over the following eight years. In the meantime, however, the Valtellina had been occupied in 1512 by the bordering Swiss canton of Grisons, which would shortly turn Protestant; this occupation would last until 1797. In those years, the sanctuary proved an important bulwark against the Lutheran and allied heresies, in a region where the large Catholic majority found itself governed by an often hostile Protestant regime. Thanks to our Ambrosian correspondent Nicola de’ Grandi for these pictures.

|

| The Apparition of the Virgin to Bl. Mario Omodei, represented in a fresco of the year 1513, only 9 years after the event. |

|

| This plaque marks the site of the apparition, “Where Mary’s feet stood.” |

|

| The high altar, made of black marble from Varenna by Giobvanni Battista Galli di Clivio in 1748. |

|

| A statue of St Michael over the altar, in gilded and silvered copper, 1768. |

|

| Part of the large gate who surrounds the sanctuary of the altar where apparition occurred, work of Pietro Antonio Citerio and Giovanni Maria Acquistapace di Morbegno, 1792. |

|

The statue of the Virgin over the altar of the apparition, by Giovanni Antonio del Maino di Pavia (1519-24). The Virgin and Child were crowned on September 29, the day of the original apparition, in 1690, by permission of the Chapter of St Peter’s Basilica. The silk and gold mantle that covers the statue was given by the people of the Valtellina during a plague that afflicted the valley in 1746. |

|

| Organ by Giuseppe Bulgarini, 1608-17 |

|

| Bulgarini is also credit with the creation of this pulpit. |

|

| The belltower, designed by Pietro Marni, was built between 1578 and 1641. The cupola was built from 1580-84 by Pompeo Bianchi, previously the chief architect of the Cathedral of nearby Como. |

|

| The ceiling of the church is covered in elaborate stucco decorations surrounding frescoed panels, a style very popular in the later 16th century Mannerist period. |

|

| A decorative panel in the choir stalls of the main sanctuary, restored in 1928, showing the Seven Founders of the Servite Order, the current custodians of the church. |

↧

The Feast of the Transfiguration 2017

Some of the hymns for Vespers of the Transfiguration in the Byzantine Rite.

![]()

Before Thy Cross, o Lord, the mountain imitated heaven, the cloud was spread out like a tent. As Thou wert transfigured, and born witness to by the Father, Peter was present with James and John, since they were also to be with Thee at the time of Thy betrayal, that seeing Thy wondrous deeds, they might not be afraid at Thy sufferings; which deem us worthy to adore in peace, for the sake of Thy great mercy.

Before Thy Cross, o Lord, taking Thy disciples unto the high mountain, Thou wast transfigured before them, shining upon them with rays of power, on the one side, in Thy love of mankind, on the other, in Thy might, wishing to show the glory of the Resurrection; of which deem us worthy in peace, as one merciful and loving of mankind.

When Thou wast transfigured on a high mountain, O Savior, having with Thee Thy chief Disciples, Thou didst shine forth in glory, showing that they who are preeminent in the sublimity of virtue, shall also be made worthy of divine glory. And Moses and Elijah, speaking with Christ, made manifest that He is the Lord of the living and the dead, and that He was the God Who spoke of old through the law and the Prophets, to Whom also the voice of the Father did bear witness from a radiant cloud, saying, “Hear ye Him, Who by the Cross hath despoiled Hades, and bestowed eternal life upon the dead.

The mountain which once was dark with smoke is honorable and holy, upon which stood Thy feet, O Lord, for the mystery hidden before the ages, at the last Thy awful Transfiguration did manifest to Peter, James and John; who, unable to bear the radiance of Thy face and the splendor of Thy raiment, were borne down upon their faces in the ground, and being overcome with astonishment, wondered as they saw Moses and Elijah speaking with Thee of the things that were to befall Thee. And a voice from the Father bore witness, saying, This is My beloved Son in Whom I am well pleased; hear ye, Him Who granteth to the world great mercy.

Before Thy Cross, o Lord, taking Thy disciples unto the high mountain, Thou wast transfigured before them, shining upon them with rays of power, on the one side, in Thy love of mankind, on the other, in Thy might, wishing to show the glory of the Resurrection; of which deem us worthy in peace, as one merciful and loving of mankind.

When Thou wast transfigured on a high mountain, O Savior, having with Thee Thy chief Disciples, Thou didst shine forth in glory, showing that they who are preeminent in the sublimity of virtue, shall also be made worthy of divine glory. And Moses and Elijah, speaking with Christ, made manifest that He is the Lord of the living and the dead, and that He was the God Who spoke of old through the law and the Prophets, to Whom also the voice of the Father did bear witness from a radiant cloud, saying, “Hear ye Him, Who by the Cross hath despoiled Hades, and bestowed eternal life upon the dead.

The mountain which once was dark with smoke is honorable and holy, upon which stood Thy feet, O Lord, for the mystery hidden before the ages, at the last Thy awful Transfiguration did manifest to Peter, James and John; who, unable to bear the radiance of Thy face and the splendor of Thy raiment, were borne down upon their faces in the ground, and being overcome with astonishment, wondered as they saw Moses and Elijah speaking with Thee of the things that were to befall Thee. And a voice from the Father bore witness, saying, This is My beloved Son in Whom I am well pleased; hear ye, Him Who granteth to the world great mercy.

↧

A Visit to Innsbruck (4): Kapuzinerkirche and Spitalkirche

The rather unassuming facade of the Capuchin church in the center Innsbruck, the Kapuzinerkloster, might cause one to pass right by it, and yet I have been told that this is the first church of the Order in the German-speaking part of Europe. It was endowed by Archduke Ferdinand II and his second wife Anna Katharina Gonzaga in 1593. The hermitage of Archduke Maximilian III was build onto the north side of the church in 1615. Appropriated by the Nazis in 1940, the monastery was re-established after the War. (Notes adapted from the sign posted outside the monastery.) In keeping with Franciscan poverty combined with postconciliar austerity, the church is quite plain, but it houses a treasure: a second painting of Our Lady by Lucas Cranach the Elder, this one of the nursing Madonna.

The Spitalkirche, or "Hospital Church," is closer to the heart of the city, on one of the busiest streets. Unfortunately, it appears that most people pass it by -- and indeed, I just heard in recent days that an announcement has been made that this church will be closed to the public at a certain point and only opened for special occasions. It can be seen on the right side of this photo, and then, on the next day (when the weather had changed), directly from the side:

This church was built by the Innbruck Baroque architect Johann Martin Gumpp in 1700-1701, adjacent to a city hospital from 1307 that was later converted into a school. An earlier church stood on this spot from 1320. Again, in keeping with the Austrians' love of Our Lady, this church houses an icon of Our Lady of Good Counsel, from Genazzano, Italy. It is located at the left side altar, surmounted by a crucifix, behind which is an old oil painting that displays the city of Innsbruck in the late Middle Ages.

To me, one of the most charming aspects of this little church is the placement of the busts of the twelve Apostles around the perimeter of the building, with a symbol of martyrdom for each, and a scroll with his name in case the symbol wasn't enough. Predictably, the pulpit on the wall caught my attention. This pulpit is even further along the side of the church than is typically the case, at least in the churches I saw in Innsbruck. It's a bit difficult to see it as connected in any way with the sanctuary.

One has to feel sorry for any organist who is stuck playing THIS instrument, which was clearly designed for musicians who never suffer from claustrophobia:

As I looked up at the ceiling, I noticed some modern frescoes -- there was no indication of the date, but the style clearly suggests the past century, from the blockish clumsiness and weirdness:

Nevertheless, it is a lovely little church that does not deserve to be shut down. It would make a good chapel for the FSSP or the ICKSP. Perhaps when Innsbruck gets a new bishop (they have been sedevacante for 2 years now), he will be forward-looking enough to entrust the church to a new generation of post-modern tradition-loving Catholics.

![]()

| The altar piece is unusual. |

| Two Capuchin martyrs from the Missions |

The Spitalkirche, or "Hospital Church," is closer to the heart of the city, on one of the busiest streets. Unfortunately, it appears that most people pass it by -- and indeed, I just heard in recent days that an announcement has been made that this church will be closed to the public at a certain point and only opened for special occasions. It can be seen on the right side of this photo, and then, on the next day (when the weather had changed), directly from the side:

This church was built by the Innbruck Baroque architect Johann Martin Gumpp in 1700-1701, adjacent to a city hospital from 1307 that was later converted into a school. An earlier church stood on this spot from 1320. Again, in keeping with the Austrians' love of Our Lady, this church houses an icon of Our Lady of Good Counsel, from Genazzano, Italy. It is located at the left side altar, surmounted by a crucifix, behind which is an old oil painting that displays the city of Innsbruck in the late Middle Ages.

One has to feel sorry for any organist who is stuck playing THIS instrument, which was clearly designed for musicians who never suffer from claustrophobia:

As I looked up at the ceiling, I noticed some modern frescoes -- there was no indication of the date, but the style clearly suggests the past century, from the blockish clumsiness and weirdness:

Nevertheless, it is a lovely little church that does not deserve to be shut down. It would make a good chapel for the FSSP or the ICKSP. Perhaps when Innsbruck gets a new bishop (they have been sedevacante for 2 years now), he will be forward-looking enough to entrust the church to a new generation of post-modern tradition-loving Catholics.

↧

↧

Why Eros and the Worship of God Are the Keys to Countering Philosophical Error

From where does our worldview come? If we are worried about the philosophical errors of modernity, it would be helpful to be able to answer this question.

If all right philosophy is derived from the adoption of right premises, the question then reduces to: how do we choose the axioms, the foundational truths, upon which the whole edifice is built?

The simple answer, it seems to me, is that most people just choose what looks good to them. It is a somewhat arbitrary process, an act of faith of sorts. Discursive reason does have a part to play in this, but in my experience, it is used most commonly to validate the intuitive choices already made, rather than to investigate their validity with a truly open mind.

Consequently, however rational and well worked out we think we present the case for the Christian worldview, unless people are ready to listen, we are unlikely to get anywhere.

If we wish to change people’s minds then there are two approaches. One is to examine their worldview rationally and point out any contradictions. As mentioned, this is least likely to convince, simply because on the whole people don’t want to listen. If people do want to listen, it might be because they are facing a crisis by which, in some way, the contradictions or inadequacies of their current worldview are slapping them in the face.

But even then, most will still only be prepared to listen if the second approach is taken as well; that is, people must be presented with a set of premises that are better and more attractive than the ones they already have. How can we do this?

I would say that this is what the method of the New Evangelization, as described by Benedict XVI, is aiming to do. (I have written an article about this, here).

For Catholics, the strongest presentation of these premises is encountered in the person of Christ in the liturgy. Through this encounter, because we are in relation with Truth, we are more likely to respond with an acceptance of the basic assumptions of, for example, the nature of existence in regard to all that we perceive around us. We say: I am - You are - it is. If this were to happen, in one stroke, the radical skepticism of much of modern philosophy would be banished, and by this we can accept the ideas of objective truth, beauty and goodness.

If this is right, then we can say that the acceptance of the pattern of truth that is the foundation of all good philosophy is made possible by the acceptance of the love of God, for to know Christ, we must love Him. As I described in a recent article, the place where this love is most powerfully offered to us is in the liturgy and the acceptance of this love is an act that is termed eros. (See A Reflection on Eros, Acedia and Christian Joy.)

I suggest, therefore, that the best preparation for the study of philosophy for Catholics, and the best defense we have against attraction to the errors of modern philosophy, is offered to us in the sacred liturgy. It sets forth a liturgical and mystagogical catechesis, which to my mind is one that is grounded in Sacred Scripture, as a priority in a Catholic education. This point has been made before. Following the work of Leo XIII (Providentissimus Deus), St Pius X stressed the importance of the study of Scripture in the formation of priests in his letter Quoniam re biblica. What about the unbaptised and those who never make it into church? How do we reach them?

The answer is that we must present Christ to them. Again this goes to Benedict XVI’s little paper on the New Evangelization. We must become supernaturally transformed and partake of the divine nature - a pixel of light in the transfigured mystical body of Christ, the Church. Then, when we relate to others we present them, in some way, in the person of Christ. People will see the pattern of love, that is the foundation of good philosophy in us and be attracted to it... or at least that’s the hope.

Once presented with Truth, people are free to either adopt or reject what they see, but they are unlikely ever to adopt it if they are never presented with it!

It is possible to discern dimly the pattern of Christ through creation. The ancient Greeks did so, as we know, through the beauty of the cosmos. But the cosmos does not reveal it as fully as the Church does.

This is why I would say that there is no true philosophy without the Faith, grace and the supernatural; and a lover of true wisdom is always a lover first of divine wisdom.

The good philosopher is really a philohagiosopher!

Above, an icon of the personification of Holy Wisdom, and belowm an ancient Russian icon of St Sophia with her three daughters, Faith, Hope and Love

If all right philosophy is derived from the adoption of right premises, the question then reduces to: how do we choose the axioms, the foundational truths, upon which the whole edifice is built?

The simple answer, it seems to me, is that most people just choose what looks good to them. It is a somewhat arbitrary process, an act of faith of sorts. Discursive reason does have a part to play in this, but in my experience, it is used most commonly to validate the intuitive choices already made, rather than to investigate their validity with a truly open mind.

Consequently, however rational and well worked out we think we present the case for the Christian worldview, unless people are ready to listen, we are unlikely to get anywhere.

If we wish to change people’s minds then there are two approaches. One is to examine their worldview rationally and point out any contradictions. As mentioned, this is least likely to convince, simply because on the whole people don’t want to listen. If people do want to listen, it might be because they are facing a crisis by which, in some way, the contradictions or inadequacies of their current worldview are slapping them in the face.

But even then, most will still only be prepared to listen if the second approach is taken as well; that is, people must be presented with a set of premises that are better and more attractive than the ones they already have. How can we do this?

I would say that this is what the method of the New Evangelization, as described by Benedict XVI, is aiming to do. (I have written an article about this, here).

For Catholics, the strongest presentation of these premises is encountered in the person of Christ in the liturgy. Through this encounter, because we are in relation with Truth, we are more likely to respond with an acceptance of the basic assumptions of, for example, the nature of existence in regard to all that we perceive around us. We say: I am - You are - it is. If this were to happen, in one stroke, the radical skepticism of much of modern philosophy would be banished, and by this we can accept the ideas of objective truth, beauty and goodness.

If this is right, then we can say that the acceptance of the pattern of truth that is the foundation of all good philosophy is made possible by the acceptance of the love of God, for to know Christ, we must love Him. As I described in a recent article, the place where this love is most powerfully offered to us is in the liturgy and the acceptance of this love is an act that is termed eros. (See A Reflection on Eros, Acedia and Christian Joy.)

I suggest, therefore, that the best preparation for the study of philosophy for Catholics, and the best defense we have against attraction to the errors of modern philosophy, is offered to us in the sacred liturgy. It sets forth a liturgical and mystagogical catechesis, which to my mind is one that is grounded in Sacred Scripture, as a priority in a Catholic education. This point has been made before. Following the work of Leo XIII (Providentissimus Deus), St Pius X stressed the importance of the study of Scripture in the formation of priests in his letter Quoniam re biblica. What about the unbaptised and those who never make it into church? How do we reach them?

The answer is that we must present Christ to them. Again this goes to Benedict XVI’s little paper on the New Evangelization. We must become supernaturally transformed and partake of the divine nature - a pixel of light in the transfigured mystical body of Christ, the Church. Then, when we relate to others we present them, in some way, in the person of Christ. People will see the pattern of love, that is the foundation of good philosophy in us and be attracted to it... or at least that’s the hope.

Once presented with Truth, people are free to either adopt or reject what they see, but they are unlikely ever to adopt it if they are never presented with it!

It is possible to discern dimly the pattern of Christ through creation. The ancient Greeks did so, as we know, through the beauty of the cosmos. But the cosmos does not reveal it as fully as the Church does.

This is why I would say that there is no true philosophy without the Faith, grace and the supernatural; and a lover of true wisdom is always a lover first of divine wisdom.

The good philosopher is really a philohagiosopher!

Above, an icon of the personification of Holy Wisdom, and belowm an ancient Russian icon of St Sophia with her three daughters, Faith, Hope and Love

↧

Chant Workshop in Columbus, Ohio, Aug. 10-12

A Gregorian chant workshop entitled The Gregorian Melody – The Expressive Power of the Word will be held by Fr. Stephen Concordia, OSB, at the Dominican Church of St Patrick in Columbus, Ohio, from Thursday, August 10, through Saturday, August 12. The church is located at 280 N. Grant Ave. The workshop will conclude with a sung Novus Ordo Mass in Latin. Suggested donation of $20 per participant at the door; registration is suggested but not required. To register or for additional information, please email or call Kathleen Tully, director of music at St Patrick, at kathleen@stpatrickcolumbus.org or 614-224-9522 ext. 152.

Topics include:

Why sing Gregorian chant today, and how should we sing it? (7:00 p.m., Thursday, August 10)

Where did the chant come from?

History and Sources

Gregorian chant is sung prayer

Singing Latin texts - Melody and Rhythm (Modes and Neumes)

7-9:00 p.m., Friday, August 11

10:00-Noon & 1-3:00pm, Saturday, August 12

Repertoire to be studied

From the Graduale Simplex: Parts of the Mass for the Schola and the Assembly

Syllabic Antiphons (Propers)

Simpler more ancient Mass Ordinaries

Fr. Stephen Concordia, O.S.B., a Benedictine monk since 1989, has more than 30 years of daily contact with the Gregorian Chant repertoire. He is assistant professor of music and director of programs in sacred music at Saint Vincent College, where he directs the Saint Vincent Camerata, the Camerata Scholars, the Saint Vincent Schola Gregoriana and a Diocesan Schola Cantorum for regular celebrations of the Mass in the Extraordinary Rite. He holds degrees from the New England Conservatory of Music, Boston (B.M.,M.M), and from the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music, Rome (Licentiate and Magistero in Organ, Licentiate and Magistero in Gregorian Chant), where he studied Gregorian Chant with Nino Albarosa and Alberto Turco.

His recent activities in the fields of Gregorian Chant pedagogy and performance include workshops and presentations at Penn State University, Bard College Conservatory, Duquesne University, National Assoc.of Pastoral Musicians (Greensburg, PA); presentations to the American Choral Directors Association: national, regional and state conventions; conducting the Saint Vincent Schola Gregoriana at Heinz Hall with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (2009, 2012); CDs with the Monastic Choir of Montecassino (Foné 1999), with the Saint Vincent Camerata Scholars (JADE 2011, 2013) and with the Schola Cantorum of Holy Family (JADE 2013); and a translation from the Italian of the chant textbook “Tones and Modes” by Alberto Turco (Torre d’Orfeo Editrice, Rome 2003). Previous positions include director of music at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, NYC, and invited professor of Gregorian Chant at the Pontifical Liturgical Institute, Rome.

Topics include:

Why sing Gregorian chant today, and how should we sing it? (7:00 p.m., Thursday, August 10)

Where did the chant come from?

History and Sources

Gregorian chant is sung prayer

Singing Latin texts - Melody and Rhythm (Modes and Neumes)

7-9:00 p.m., Friday, August 11

10:00-Noon & 1-3:00pm, Saturday, August 12

Repertoire to be studied

From the Graduale Simplex: Parts of the Mass for the Schola and the Assembly

Syllabic Antiphons (Propers)

Simpler more ancient Mass Ordinaries

Fr. Stephen Concordia, O.S.B., a Benedictine monk since 1989, has more than 30 years of daily contact with the Gregorian Chant repertoire. He is assistant professor of music and director of programs in sacred music at Saint Vincent College, where he directs the Saint Vincent Camerata, the Camerata Scholars, the Saint Vincent Schola Gregoriana and a Diocesan Schola Cantorum for regular celebrations of the Mass in the Extraordinary Rite. He holds degrees from the New England Conservatory of Music, Boston (B.M.,M.M), and from the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music, Rome (Licentiate and Magistero in Organ, Licentiate and Magistero in Gregorian Chant), where he studied Gregorian Chant with Nino Albarosa and Alberto Turco.

His recent activities in the fields of Gregorian Chant pedagogy and performance include workshops and presentations at Penn State University, Bard College Conservatory, Duquesne University, National Assoc.of Pastoral Musicians (Greensburg, PA); presentations to the American Choral Directors Association: national, regional and state conventions; conducting the Saint Vincent Schola Gregoriana at Heinz Hall with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (2009, 2012); CDs with the Monastic Choir of Montecassino (Foné 1999), with the Saint Vincent Camerata Scholars (JADE 2011, 2013) and with the Schola Cantorum of Holy Family (JADE 2013); and a translation from the Italian of the chant textbook “Tones and Modes” by Alberto Turco (Torre d’Orfeo Editrice, Rome 2003). Previous positions include director of music at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, NYC, and invited professor of Gregorian Chant at the Pontifical Liturgical Institute, Rome.

↧

Bishop Elliott on the Recent PCED Clarification

Our thanks to Bishop Peter Elliott, Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Melbourne, Australia, for these observations on the different forms of Pontifical Mass. His Excellency is of course well-known to our readers for his many writings on liturgical matters, and his books The Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite and Ceremonies of the Liturgical Year.

![]()

But Were There Exceptions to the Rule?

A comment on the clarification of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei

The clarification of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei is to be welcomed, so as to ensure that the distinctions between the three forms of a Pontifical Mass are maintained in the Extraordinary Form. (editor’s note: the solemn high Pontifical, the Missa praelatia, and the Mass in the Presence of a bishop.) But let us not imagine it has always been as simple as that. In mission territories, which came under the Sacred Congregation Propaganda Fidei, I wonder what privileges and modifications were available to bishops in celebrating Mass in their own territory. Some research would be welcome. Until 1978 my own country, Australia, came under Propaganda Fidei and was deemed to be a “mission territory”. One thus has some historical intimations of a certain flexibility.

In 19th-century rural Australia, newspaper reports of the blessing and opening of new churches describe the bishop celebrating a “High Mass”, with an assistant priest, deacon and subdeacon, local clergy who are always named. There is no mention of deacons of honour. Unless this was Solemn Pontifical Mass at the faldstool, these reports suggest that Ordinaries celebrated a modified form of Solemn Mass at the Throne.

As was normal in 19th-century colonial society, the music was of a high standard, Masses by Haydn, etc. with a local orchestra or band, and often soloists were imported from the bigger cities. The music was an ecumenical effort, as was the collection taken up to build the new church, that is, up to the later years of the century, when rising Irish nationalism smothered nascent ecumenism.

In 19th-century Melbourne, when our immense Gothic cathedral of St Patrick rose on the Eastern Hill, Pontifical Mass at the Faldstool was favoured for major events, with Bishop Corbett of Sale as celebrant, and the Metropolitan and other Ordinaries assisting in choir. Bishop Corbett had a legendary voice; the other prelates admitted that they were not good singers, nor could they project the voice as well as he could, in an era before microphones.

Photographic evidence is also interesting. When Bishop Phelan of Sale consecrated his modest cathedral in 1915, he celebrated Mass with a deacon and subdeacon, who had no doubt acted as the assisting deacons during the long and complex rites that preceded the Mass. He did not wear dalmatic and tunicle, but they are fully vested. The Metropolitan was represented by the then-Coadjutor Archbishop of Melbourne, Dr Daniel Mannix, in choir dress. Was this a Pontifical Mass in a modified form?

However, before the several interesting reforms of the rites for the dedication of church, the long ceremonies were very tiring for aging prelates, also expected to fast for the occasion. Therefore, the Mass at the Consecration of a church was often only a Pontifical Low Mass, as happened when Auxiliary Bishop Jerome Sebastian of Baltimore consecrated the new cathedral of Mary Our Queen on October 13th, 1959.

Returning to Australia, in 1966 a later Bishop of Sale, Dr Patrick Lyons, celebrated the centenary Mass of the Sisters of St Joseph, founded by St Mary of the Cross McKillop. Here, during the post-conciliar transition, we see the first blurring of the three pontifical forms of Mass. The deacons of honour are replaced by a deacon and subdeacon at the throne, with the assistant priest in cope making perhaps his final appearance. Bishop Lyons was punctilious and traditional.

After Vatican II, a major factor that broke down the classical distinction was the arrival of ritual Masses for the Sacraments, in particular, Confirmation. I celebrate these Masses every week in the Winter-Spring Confirmation season in Melbourne (May to November). The variations in the Ordinary Form are wide, ranging from a solemn form with fine music to a minimalist affair with no servers and the parish priest juggling with my chrismatory and crozier. The music at these latter events is best forgotten.

It should also be remembered that Mass for the Ordination to the Priesthood before Vatican II was often a Pontifical Low Mass. The ordaining prelate was bound to wear pontifical vestments; he used the crozier and two miters, and, in accord with the rubrics, he was assisted by two chaplains in surplice. The common and proper were sung, apparently even before the wider provision granted in 1958 for singing at Low Mass. It was thus a much more modest liturgy than our post-conciliar ordinations with hordes of concelebrants, wandering deacons and tumbling MCs.

But those two chaplains in the old rite had a specific role. They strictly supervised the word and action of the bishop to ensure validity and liceity. One famed bishop had a penchant for reaching out and turning two pages of the Pontificale at once. Now that could be a problem, particularly before Pope Pius XII defined the matter and form in 1947. Two beady-eyed Redemptorists kept him under control.

Our post-conciliar episcopal ordinations should be easier, with matter and form clearly indicated in the rite, thanks to Dom Botte. However, recently I watched an elaborate episcopal ordination in Italy. As far as I could see, the chief consecrator alone said the form, and, although they had laid hands on the candidate, the twenty aging co-consecrators seemed unaware that they were also meant to articulate the form! But not long ago during a rather prominent episcopal ordination in the US, the ancient practice of deacons imposing the Book of the Gospels just did not happen. An MC forgot? Not good. Bring back those strict chaplains.

In 19th-century rural Australia, newspaper reports of the blessing and opening of new churches describe the bishop celebrating a “High Mass”, with an assistant priest, deacon and subdeacon, local clergy who are always named. There is no mention of deacons of honour. Unless this was Solemn Pontifical Mass at the faldstool, these reports suggest that Ordinaries celebrated a modified form of Solemn Mass at the Throne.

As was normal in 19th-century colonial society, the music was of a high standard, Masses by Haydn, etc. with a local orchestra or band, and often soloists were imported from the bigger cities. The music was an ecumenical effort, as was the collection taken up to build the new church, that is, up to the later years of the century, when rising Irish nationalism smothered nascent ecumenism.

In 19th-century Melbourne, when our immense Gothic cathedral of St Patrick rose on the Eastern Hill, Pontifical Mass at the Faldstool was favoured for major events, with Bishop Corbett of Sale as celebrant, and the Metropolitan and other Ordinaries assisting in choir. Bishop Corbett had a legendary voice; the other prelates admitted that they were not good singers, nor could they project the voice as well as he could, in an era before microphones.

Photographic evidence is also interesting. When Bishop Phelan of Sale consecrated his modest cathedral in 1915, he celebrated Mass with a deacon and subdeacon, who had no doubt acted as the assisting deacons during the long and complex rites that preceded the Mass. He did not wear dalmatic and tunicle, but they are fully vested. The Metropolitan was represented by the then-Coadjutor Archbishop of Melbourne, Dr Daniel Mannix, in choir dress. Was this a Pontifical Mass in a modified form?

However, before the several interesting reforms of the rites for the dedication of church, the long ceremonies were very tiring for aging prelates, also expected to fast for the occasion. Therefore, the Mass at the Consecration of a church was often only a Pontifical Low Mass, as happened when Auxiliary Bishop Jerome Sebastian of Baltimore consecrated the new cathedral of Mary Our Queen on October 13th, 1959.

Returning to Australia, in 1966 a later Bishop of Sale, Dr Patrick Lyons, celebrated the centenary Mass of the Sisters of St Joseph, founded by St Mary of the Cross McKillop. Here, during the post-conciliar transition, we see the first blurring of the three pontifical forms of Mass. The deacons of honour are replaced by a deacon and subdeacon at the throne, with the assistant priest in cope making perhaps his final appearance. Bishop Lyons was punctilious and traditional.

After Vatican II, a major factor that broke down the classical distinction was the arrival of ritual Masses for the Sacraments, in particular, Confirmation. I celebrate these Masses every week in the Winter-Spring Confirmation season in Melbourne (May to November). The variations in the Ordinary Form are wide, ranging from a solemn form with fine music to a minimalist affair with no servers and the parish priest juggling with my chrismatory and crozier. The music at these latter events is best forgotten.

It should also be remembered that Mass for the Ordination to the Priesthood before Vatican II was often a Pontifical Low Mass. The ordaining prelate was bound to wear pontifical vestments; he used the crozier and two miters, and, in accord with the rubrics, he was assisted by two chaplains in surplice. The common and proper were sung, apparently even before the wider provision granted in 1958 for singing at Low Mass. It was thus a much more modest liturgy than our post-conciliar ordinations with hordes of concelebrants, wandering deacons and tumbling MCs.

But those two chaplains in the old rite had a specific role. They strictly supervised the word and action of the bishop to ensure validity and liceity. One famed bishop had a penchant for reaching out and turning two pages of the Pontificale at once. Now that could be a problem, particularly before Pope Pius XII defined the matter and form in 1947. Two beady-eyed Redemptorists kept him under control.

Our post-conciliar episcopal ordinations should be easier, with matter and form clearly indicated in the rite, thanks to Dom Botte. However, recently I watched an elaborate episcopal ordination in Italy. As far as I could see, the chief consecrator alone said the form, and, although they had laid hands on the candidate, the twenty aging co-consecrators seemed unaware that they were also meant to articulate the form! But not long ago during a rather prominent episcopal ordination in the US, the ancient practice of deacons imposing the Book of the Gospels just did not happen. An MC forgot? Not good. Bring back those strict chaplains.

↧

Monastic Compline

A nice recording of the Hour of Compline according to the Monastic Breviary.

↧

↧

St Lawrence, Deacon and Martyr, August 10th

For the latest in our occasional series on the Saints of the Roman Canon, here are some pictures of St Lawrence. He was one of the seven deacons of the Roman church under Pope St Sixtus II, who was martyred only a few days before him, in the reign of the Emperor Valerian (253-260). He is one of the most celebrated Roman martyrs.

Lawrence is generally shown wearing the deacon’s vestment, the dalmatic, and holding a book of psalms, and alms for the poor. He also appears with the general symbol of martyrdom, the palm branch, and his specific symbol, the grid iron on which he was tortured to death. You can read about his life on New Advent here.

Above, St Lawrence painted by Spinello Aretino, (Italian, 14th century), and below, by Bernardo Strozzi, (Italian, 17th century). The Strozzi painting is called The Charity of St Lawrence, since as part of his duties as deacon, he distributed alms and the treasures of the church, that were coveted by the Emperor. Lawrence continued to distribute alms, and told the Emperor that the poor themselves were the real treasures of the Church.

And finally, in the Niccoline Chapel in the Vatican, there is a series of frescoes painted by Fra Angelico.

This is one of a series of articles written to highlight the great feasts and the Saints of the Roman Canon. All are connected to a single opening essay, in which I set out principles by which we might create a canon of art for Roman Rite churches and a schema that would guide the placement of such images in a church, which you can read here.

In these essays, I plan to cover the key elements of images of the Saints of the Roman Canon (Eucharistic Prayer I) and the major feasts of the year.

For the fullest presentation of the principles of sacred art for the liturgy, take the Master’s of Sacred Arts: www.Pontifex.University.

Lawrence is generally shown wearing the deacon’s vestment, the dalmatic, and holding a book of psalms, and alms for the poor. He also appears with the general symbol of martyrdom, the palm branch, and his specific symbol, the grid iron on which he was tortured to death. You can read about his life on New Advent here.

Above, St Lawrence painted by Spinello Aretino, (Italian, 14th century), and below, by Bernardo Strozzi, (Italian, 17th century). The Strozzi painting is called The Charity of St Lawrence, since as part of his duties as deacon, he distributed alms and the treasures of the church, that were coveted by the Emperor. Lawrence continued to distribute alms, and told the Emperor that the poor themselves were the real treasures of the Church.

And finally, in the Niccoline Chapel in the Vatican, there is a series of frescoes painted by Fra Angelico.

This is one of a series of articles written to highlight the great feasts and the Saints of the Roman Canon. All are connected to a single opening essay, in which I set out principles by which we might create a canon of art for Roman Rite churches and a schema that would guide the placement of such images in a church, which you can read here.

In these essays, I plan to cover the key elements of images of the Saints of the Roman Canon (Eucharistic Prayer I) and the major feasts of the year.

For the fullest presentation of the principles of sacred art for the liturgy, take the Master’s of Sacred Arts: www.Pontifex.University.

↧

Assumption Celebration at St Mary’s in Norwalk, Connecticut, August 19

St Mary’s in Norwalk, Connecticut, will celebrate a Solemn Mass High on Saturday, August 19th, for the external solemnity of the church’s patronal feast, the Assumption, in the presence of the local ordinary, His Excellency Frank Caggiano, Bishop of Bridgeport. The Mass will begin at 4 pm, followed by a procession through the local streets, and dinner at the parish hall. (For information about tickets to the dinner, see the parish website.)

St Mary’s is well-known for its excellent music; this Mass will include, in addition to the Gregorian propers, Mozart’s Spatzenmesse (Missa brevis in C- major) and motets by Elgar, Guerrero, Mozart and Victoria.

St Mary’s is well-known for its excellent music; this Mass will include, in addition to the Gregorian propers, Mozart’s Spatzenmesse (Missa brevis in C- major) and motets by Elgar, Guerrero, Mozart and Victoria.

↧

The Cathedral of Pistoia

As a follow-up to a recent post on the relic of St James the Greater kept at the cathedral of St Zeno in Pistoia, here are some photos of the main church which I took during a wonderful nighttime tour last November. These hardly show all of the church’s artistic treasures, some of which could not really be photographed in the low light.

| The Romanesque bell-tower and façade, both of the mid-twelfth century, with considerable alterations and additions made in subsequent centuries. |

| A Madonna of the 15th century. |

In the right aisle, a triptych of the Crucifixion, with the Madonna, and Ss John, James and Jerome, (author unknown, 1424), and a copy of the Annunciation by Passignano. |

| Preaching pulpit designed by the famous art historian Giorgio Vasari (1560). |

| Some bare remains of medieval frescoes in the clerestory. |

| Several pieces of the balustrade which formerly surrounded the medieval presbytery are preserved in the cathedral crypt. |

| A sculpture of the Visitation; St Zachary is shown on the right with a cane to indicate his old age. |

| The Last Supper and the Arrest in the Garden. |

↧

The Second Vatican Council and the Lectionary—Part 3: The First and Second Sessions of the Council (1962-1963)

Note: This is the final part of a three-part series. Part One, on the antepreparatory period, can be found here, and Part Two, on the preparatory period, can be found here.

The Second Vatican Council was solemnly opened on 11 October 1962, with Pope John XXIII's declaration Gaudet Mater Ecclesiae. [1] Discussion on the Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (hereafter SC), began on 22 October 1962, and would continue throughout the first and second sessions of the Council until its solemn promulgation by Pope Paul VI on 4 December 1963. For the purposes of this short series, we are not so concerned with the history of the Council itself, or of all the discussion that was had over SC; there are many books and articles that examine various aspects of both of these. [2] We will be looking specifically at what the Fathers had to say about the lectionary, and the question of its potential reform.

Before we begin our brief examination, it should be noted that the Acta Synodalia Sacrosancti Concilii Oecumenici Vaticani II for the first two sessions (ten volumes) are absolutely vital reference material for anyone wishing to read exactly what was said on the Council floor about the constitution on the liturgy (along with any written submissions of the Fathers). I have previously made these freely available at NLM: the Acta Synodalia (hereafter AS) for the first session can be found here, and those for the second session can be found here.