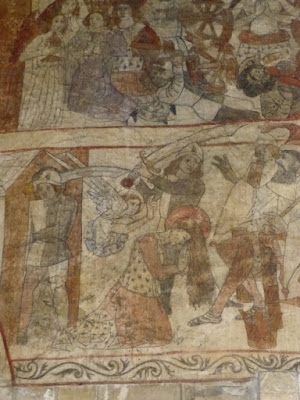

The Apocalypse Prize 2017 is a religious art competition which as been developed to stimulate interest in Medieval Art as a resource for contemporary religious artists. This is an international, free entry painting competition which is open to all; the deadline this year is December 31, 2017, and the grand prize awarded is $10,000. Subjects and media are specified on the following website, http://apocalypseprize.com, where you can also find several videos and essays which are intended to facilitate a deeper understanding of the use of the figurative language of Sacred Scripture in Medieval Art. You can also read about how the competition was instituted by artist Gloria Thomas in this article from 2015.

The Apocalypse Art Prize 2017

↧

↧

A Combination Tenebrae Hearse and Paschal Candlestick

From the Facebook page of the Fraternity of St Peter’s English apostolates comes this rather ingenious explanation of how they also use a Tenebrae hearse as a Paschal candlestick. Although this is written a humorous vein, the device itself is real, as you can see in the pictures below.

LITURGICAL REVOLUTION!

Exclusive release by FSSP England [owner of the patent & trademark all over the tradisphere - please use this acronym for your order: tiopcsth]: The two-in-one paschal-candle-stand-tenebrae-hearse!

INTERVIEW WITH THE INVENTORS

- What was your inspiration?

- Eco-friendliness matters to us. We wanted to spare the trees! We started with a bulk order of Baronius EF missals for our parishioners, thus avoiding the waste of hundreds of printed Sunday sheets, normally thrown into the bin after being used once only. Then we recycled our palms from last Palm Sunday, according to the EF rubrics stating that those must provide the combustible for the ashes blessed on Ash Wednesday the following year. Lastly, we saved on cleaning agents for our kneeling pads, suggesting people’s knees may rest on them rather than their feet: it made the pads much cleaner and nature-unfriendly detergents were got rid off.

- Thank you for these encouraging examples of liturgical eco-friendliness. We now come to your liturgical revolution. As a reminder for our readers, a tenebrae hearse is the free standing triangular candelabra holding fifteen unbleached candles, extinguished one after the other while singing Matins and Lauds in the Extraordinary Form during the Sacred Triduum. Had you worked on tenebrae hearses before?

- Yes, while in Reading we made a first attempt with wrought iron. It worked well and another church in the South requested to copy it. It is now used in London. But for all our attempts, we could not find a hearse when we moved North. All we had was a good sturdy oak stand for the paschal candle. Rather than have another stand and the triangle made from scratch, we thought it would be much simpler to design only the triangle, so as to rest on the spike of the existing paschal candle stand.

- But where will your paschal candle fit then? Do you have a spare stand for it?

- This is the trick! No need for a second one, as by definition, the paschal candle is never used but after tenebrae are completed. Tenebrae end on Holy Saturday morning. Extinguishing the fifteen candles on the hearse one by one symbolises Christ’s passion and death. (See my note below.) But the paschal candle blessed at the Paschal Vigil symbolises Christ rising. All we need to do is take the triangle off the spike in the morning and set the paschal candle on it instead in the evening. Theologically, it makes a lot of sense to use one and the same stand for the two successive liturgical stages. It is death and resurrection.

- Congratulations! This is a true liturgical revolution. As to the future, if we may enquire, rumour has it that Apple contacted you to produce their next i-hearse...

- We are not at liberty to comment on this. But we invite all to come to St Mary’s Warrington during Holy Week and pray with us for a very soul-friendly Sacred Triduum.

NLM editor’s comment: Traditionally, the extinguishing of the candles during Tenebrae was understood to represent the Apostles and the two Marys, Magdalene and the wife of Cleophas, falling asleep during the Lord’s Passion, while the last candle, which is not extinguished on the hearse, represents Christ Himself, who remains the Light of the World even in His suffering and death. (I once read somewhere that the SRC several times forbade a custom which emerged from this interpretation, that of having a white candle for the last one that is not extinguished, rather than one of unbleached wax.) The removal of the candle and its placement behind the altar during the Miserere at the end of Lauds symbolizes His burial, and taking it out and showing to the people looks forward to the Rsurrection. This tradition would make the use described here even more appropriate, since the Paschal candle would then stand exactly where the last candle stands on the hearse.

It may be objected that a Tenebrae hearse should be very somber and simple, while it is more appropriate that a Paschal candle should be something festive and beautiful, as seen, for example, in the contrast between the two objects in the Roman basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

In the case of the two-in-one device seen above, this could easily be remedied by placing decorations on it when it is used as a Paschal candlestick, which was generally done anyway back in the day.

LITURGICAL REVOLUTION!

Exclusive release by FSSP England [owner of the patent & trademark all over the tradisphere - please use this acronym for your order: tiopcsth]: The two-in-one paschal-candle-stand-tenebrae-hearse!

INTERVIEW WITH THE INVENTORS

- What was your inspiration?

- Eco-friendliness matters to us. We wanted to spare the trees! We started with a bulk order of Baronius EF missals for our parishioners, thus avoiding the waste of hundreds of printed Sunday sheets, normally thrown into the bin after being used once only. Then we recycled our palms from last Palm Sunday, according to the EF rubrics stating that those must provide the combustible for the ashes blessed on Ash Wednesday the following year. Lastly, we saved on cleaning agents for our kneeling pads, suggesting people’s knees may rest on them rather than their feet: it made the pads much cleaner and nature-unfriendly detergents were got rid off.

- Thank you for these encouraging examples of liturgical eco-friendliness. We now come to your liturgical revolution. As a reminder for our readers, a tenebrae hearse is the free standing triangular candelabra holding fifteen unbleached candles, extinguished one after the other while singing Matins and Lauds in the Extraordinary Form during the Sacred Triduum. Had you worked on tenebrae hearses before?

- Yes, while in Reading we made a first attempt with wrought iron. It worked well and another church in the South requested to copy it. It is now used in London. But for all our attempts, we could not find a hearse when we moved North. All we had was a good sturdy oak stand for the paschal candle. Rather than have another stand and the triangle made from scratch, we thought it would be much simpler to design only the triangle, so as to rest on the spike of the existing paschal candle stand.

- But where will your paschal candle fit then? Do you have a spare stand for it?

- This is the trick! No need for a second one, as by definition, the paschal candle is never used but after tenebrae are completed. Tenebrae end on Holy Saturday morning. Extinguishing the fifteen candles on the hearse one by one symbolises Christ’s passion and death. (See my note below.) But the paschal candle blessed at the Paschal Vigil symbolises Christ rising. All we need to do is take the triangle off the spike in the morning and set the paschal candle on it instead in the evening. Theologically, it makes a lot of sense to use one and the same stand for the two successive liturgical stages. It is death and resurrection.

- Congratulations! This is a true liturgical revolution. As to the future, if we may enquire, rumour has it that Apple contacted you to produce their next i-hearse...

- We are not at liberty to comment on this. But we invite all to come to St Mary’s Warrington during Holy Week and pray with us for a very soul-friendly Sacred Triduum.

NLM editor’s comment: Traditionally, the extinguishing of the candles during Tenebrae was understood to represent the Apostles and the two Marys, Magdalene and the wife of Cleophas, falling asleep during the Lord’s Passion, while the last candle, which is not extinguished on the hearse, represents Christ Himself, who remains the Light of the World even in His suffering and death. (I once read somewhere that the SRC several times forbade a custom which emerged from this interpretation, that of having a white candle for the last one that is not extinguished, rather than one of unbleached wax.) The removal of the candle and its placement behind the altar during the Miserere at the end of Lauds symbolizes His burial, and taking it out and showing to the people looks forward to the Rsurrection. This tradition would make the use described here even more appropriate, since the Paschal candle would then stand exactly where the last candle stands on the hearse.

It may be objected that a Tenebrae hearse should be very somber and simple, while it is more appropriate that a Paschal candle should be something festive and beautiful, as seen, for example, in the contrast between the two objects in the Roman basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

In the case of the two-in-one device seen above, this could easily be remedied by placing decorations on it when it is used as a Paschal candlestick, which was generally done anyway back in the day.

↧

Bringing Education in Sacred Arts Into the Mainstream - Take Workshops for Credit

I am pleased to announce that Pontifex University is now offering studio credit for its Masters in Sacred Arts through established teachers offering workshops around the world. As the first three in a number of developing partnerships in a range of artistic pursuits (more news to follow soon), students on the MSA program now have an option of taking studio credit through icon painting courses run by the following partners: OQ Farm, Bethlehem Icon Center and Hexaemeron.

Just to give you an idea, typically one 5-day course with project work earns one credit at the Masters level. Students pay the teacher for the course as normal, and when they complete to the satisfaction of the teacher, they pay $150 per credit to Pontifex University.

Hexaemeron.org offers icon painting and icon carving through a series of 5-day workshops around the US and Canada. Their expert teachers include masters Jonathan Pageau, who carves icons, and Marek Czarnecki.

The Bethlehem Icon Center has courses and even a two year diploma taught by director and founder Ian Knowles. Classes are in English and you work alongside local Palestinian Christians; the Melkite Patriarch of Jerusalem is a patron of the school. The school offers short courses which are extremely good value, and the savings on the cost of the class alone would pay for a large proportion of travel and accommodation, which is very reasonably priced in Bethlehem. The next one is in April, ending the day before Holy Thursday.

And last but certainly not least, the OQ Farm is an artists’ retreat in beautiful Vermont in New England, which offers a series of workshops through the summer. Keri Wiederspahn, the director, herself an accomplished icon painter, has arranged for well known Greek iconographer George Kordis and Russian icongraphers Anton and Ekaterina Daineko to teach residential workshops in this spectacular setting. They are organized for the latter part of the summer and fall. In addition, in the fall, I will be teaching a Way of Beauty retreat at the OQ Farm, in which attendees learn about and experience the traditional formation of artists, so that they understand how it engendered creativity and an ability to apprehend beauty. It is appropriate for artists in any creative pursuit.

This is the next stage in bringing the teaching of traditional arts further into mainstream education for both artists and potential patrons, offering high quality courses that we hope will raise the standard of art in our churches, help to evangelize the culture, and draw people to the faith. My personal goal is to see sacred art viewed as a profession with the same respect given to architects. That won’t happen, however, until there is evidence of high quality art that serves the liturgy of the Church. This process of education will need to draw in all people, patrons, artists and worshipers, if it is to be successful.

Below, George Kordis, who teaches at the OQ Farm; an example of icon relief carving by Jonathan Pageau; and Ian Knowles teaching in Bethlehem.

Just to give you an idea, typically one 5-day course with project work earns one credit at the Masters level. Students pay the teacher for the course as normal, and when they complete to the satisfaction of the teacher, they pay $150 per credit to Pontifex University.

Hexaemeron.org offers icon painting and icon carving through a series of 5-day workshops around the US and Canada. Their expert teachers include masters Jonathan Pageau, who carves icons, and Marek Czarnecki.

The Bethlehem Icon Center has courses and even a two year diploma taught by director and founder Ian Knowles. Classes are in English and you work alongside local Palestinian Christians; the Melkite Patriarch of Jerusalem is a patron of the school. The school offers short courses which are extremely good value, and the savings on the cost of the class alone would pay for a large proportion of travel and accommodation, which is very reasonably priced in Bethlehem. The next one is in April, ending the day before Holy Thursday.

And last but certainly not least, the OQ Farm is an artists’ retreat in beautiful Vermont in New England, which offers a series of workshops through the summer. Keri Wiederspahn, the director, herself an accomplished icon painter, has arranged for well known Greek iconographer George Kordis and Russian icongraphers Anton and Ekaterina Daineko to teach residential workshops in this spectacular setting. They are organized for the latter part of the summer and fall. In addition, in the fall, I will be teaching a Way of Beauty retreat at the OQ Farm, in which attendees learn about and experience the traditional formation of artists, so that they understand how it engendered creativity and an ability to apprehend beauty. It is appropriate for artists in any creative pursuit.

This is the next stage in bringing the teaching of traditional arts further into mainstream education for both artists and potential patrons, offering high quality courses that we hope will raise the standard of art in our churches, help to evangelize the culture, and draw people to the faith. My personal goal is to see sacred art viewed as a profession with the same respect given to architects. That won’t happen, however, until there is evidence of high quality art that serves the liturgy of the Church. This process of education will need to draw in all people, patrons, artists and worshipers, if it is to be successful.

Below, George Kordis, who teaches at the OQ Farm; an example of icon relief carving by Jonathan Pageau; and Ian Knowles teaching in Bethlehem.

↧

Ash Wednesday 2017 Photopost

As always, thanks to all the readers who send in photographs of their Ash Wednesday liturgies. Our headliner is definitely a first for NLM: ash-colored vestments (couleur cendrée) from the Fraternity of St Peter’s church in Lyon, a classically medieval custom of the ancient use of Lyon. We wish you all a blessed and holy Lenten season. Our next photopost will cover the feasts of St Joseph and the Annunciation, and Laetare Sunday, which all fall within a week of each other this year; a request will be posted the week before.

Collegiate Church of St Just - Lyon (FSSP)

|

| Tradition is for the young! |

St Catherine Labouré - Middletown, New Jersey

Bethany House Chapel - Singapore

This is a chapel in a home for retired priests; very edifying to see the faithful put up with a bit of crowding to attend the holy Mass on this important day!St Stephen’s - Portland, Oregon

Parish of the Holy Redeemer - Quezon City, Philippine Islands

Santa Maria degli Angeli - Civitanova Alta, Italy

This church has been hosting the Summorum Pontificum group of Tolentino since their church of the Sacred Heart was damaged in the recent spate of earthquakes.St Joseph Oratory - Detroit, Michigan (ICK)

St Margaret Mary - Oakland California (ICK)

Parish of St Mary - Kalamazoo, Michigan

| And again, tradition is for the young! |

St Eugène - Paris, France

home of our friends of the Schola St Cécile

↧

International Declaration on Sacred Music "Cantate Domino"

Today, March 5, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Instruction Musicam Sacram(promulgated March 5, 1967), a Declaration on Sacred Music Cantate Domino, signed by over 200 musicians, pastors, and scholars from around the world, has been published in six languages (English, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and German). This declaration argues for the continued relevance and importance of traditional sacred music and critiques the numerous serious deviations from it that have plagued the Catholic Church for the past half-century.

Readers of NLM are encouraged to read the text (reproduced below in full) and to disseminate it far and wide as a rallying-point for Catholics who love our great heritage, and for all men and women who value high culture and the fine arts as expressions of the spiritual nobility of the human person made in God's image.

We, the undersigned — musicians, pastors, teachers, scholars, and lovers of sacred music — humbly offer this statement to the Catholic community around the world, expressing our great love for the Church’s treasury of sacred music and our deep concerns about its current plight.

Introduction

![]()

Readers of NLM are encouraged to read the text (reproduced below in full) and to disseminate it far and wide as a rallying-point for Catholics who love our great heritage, and for all men and women who value high culture and the fine arts as expressions of the spiritual nobility of the human person made in God's image.

“CANTATE DOMINO CANTICUM NOVUM”

A Statement on the Current Situation of Sacred Music

We, the undersigned — musicians, pastors, teachers, scholars, and lovers of sacred music — humbly offer this statement to the Catholic community around the world, expressing our great love for the Church’s treasury of sacred music and our deep concerns about its current plight.

Introduction

Cantate Domino canticum novum, cantate Domino omnis terra (Psalm 96): this singing to God’s glory has resonated for the whole history of Christianity, from the very beginning to the present day. Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition alike bear witness to a great love for the beauty and power of music in the worship of Almighty God. The treasury of sacred music has always been cherished in the Catholic Church by her saints, theologians, popes, and laypeople.

Such love and practice of music is witnessed to throughout Christian literature and in the many documents that the Popes have devoted to sacred music, from John XXII’s Docta Sanctorum Patrum (1324) and Benedict XIV’s Annus Qui (1749) down to Saint Pius X’s Motu Proprio Tra le Sollecitudini (1903), Pius XII’s Musicae Sacrae Disciplina (1955), Saint John Paul II’s Chirograph on Sacred Music (2003), and so on. This vast amount of documentation impels us to take with utter seriousness the importance and the role of music in the liturgy. This importance is related to the deep connection between the liturgy and its music, a connection that goes two ways: a good liturgy allows for splendid music, but a low standard of liturgical music also tremendously affects the liturgy. Nor can the ecumenical importance of music be forgotten, when we know that other Christian traditions — such as Anglicans, Lutherans, and the Eastern Orthodox — have high esteem for the importance and dignity of sacred music, as witnessed by their own jealously-guarded “treasuries.”

We are observing an important milestone, the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of the Instruction on Music in the Liturgy, Musicam Sacram, on March 5, 1967, under the pontificate of Blessed Paul VI. Re-reading the document today, we cannot avoid thinking of the via dolorosa of sacred music in the decades following Sacrosanctum Concilium. Indeed, what was happening in some factions of the Church at that time (1967) was not at all in line with Sacrosantum Concilium or with Musicam Sacram. Certain ideas that were never present in the Council’s documents were forced into practice, sometimes with a lack of vigilance from clergy and ecclesiastical hierarchy. In some countries the treasury of sacred music that the Council asked to be preserved was not only not preserved, but even opposed. And this quite against the Council, which clearly stated:

The Current Situation

In light of the mind of the Church so frequently expressed, we cannot avoid being concerned about the current situation of sacred music, which is nothing short of desperate, with abuses in the area of sacred music now almost the norm rather than the exception. We shall summarize here some of the elements that contribute to the present deplorable situation of sacred music and of the liturgy.

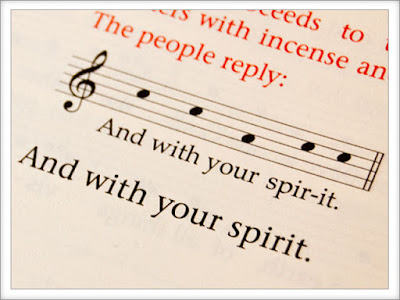

1. There has been a loss of understanding of the “musical shape of the liturgy,” that is, that music is an inherent part of the very essence of liturgy as public, formal, solemn worship of God. We are not merely to sing at Mass, but to sing the Mass. Hence, as Musicam Sacram itself reminded us, the priest’s parts should be chanted to the tones given in the Missal, with the people making the responses; the singing of the Ordinary of the Mass in Gregorian chant or music inspired by it should be encouraged; and the Propers of the Mass, too, should be given the pride of place that befits their historical prominence, their liturgical function, and their theological depth. Similar points apply to the singing of the Divine Office. It is an exhibition of the vice of “liturgical sloth” to refuse to sing the liturgy, to use “utility music” rather than sacred music, to refuse to educate oneself or others about the Church’s tradition and wishes, and to put little or no effort and resources into the building up of a sacred music program.

2. This loss of liturgical and theological understanding goes hand-in-hand with an embrace of secularism. The secularism of popular musical styles has contributed to a desacralization of the liturgy, while the secularism of profit-based commercialism has reinforced the imposition of mediocre collections of music upon parishes. It has encouraged an anthropocentrism in the liturgy that undermines its very nature. In vast sectors of the Church nowadays there is an incorrect relationship with culture, which can be seen as a “web of connections.” With the actual situation of our liturgical music (and of the liturgy itself, because the two are intertwined), we have broken this web of connection with our past and tried to connect with a future that has no meaning without its past. Today, the Church is not actively using her cultural riches to evangelize, but is mostly used by a prevalent secular culture, born in opposition to Christianity, which destabilizes the sense of adoration that is at the heart of the Christian faith.

In his homily for the feast of Corpus Christi on June 4, 2015, Pope Francis has spoken of “the Church’s amazement at this reality [of the Most Holy Eucharist]. . . An astonishment which always feeds contemplation, adoration, and memory.” In many of our Churches around the world, where is this sense of contemplation, this adoration, this astonishment for the mystery of the Eucharist? It is lost because we are living a sort of spiritual Alzheimer’s, a disease that is taking our spiritual, theological, artistic, musical and cultural memories away from us. It has been said that we need to bring the culture of every people into the liturgy. This may be right if correctly understood, but not in the sense that the liturgy (and the music) becomes the place where we have to exalt a secular culture. It is the place where the culture, every culture, is brought to another level and purified.

3. There are groups in the Church that push for a “renewal” that does not reflect Church teaching but rather serves their own agenda, worldview, and interests. These groups have members in key leadership positions from which they put into practice their plans, their idea of culture, and the way we have to deal with contemporary issues. In some countries powerful lobbies have contributed to the de facto replacement of liturgical repertoires faithful to the directives of Vatican II with low-quality repertoires. Thus, we end up with repertoires of new liturgical music of very low standards as regards both the text and the music. This is understandable when we reflect that nothing of lasting worth can come from a lack of training and expertise, especially when people neglect the wise precepts of Church tradition:

4. This disdain for Gregorian chant and traditional repertoires is one sign of a much bigger problem, that of disdain for Tradition. Sacrosanctum Concilium teaches that the musical and artistic heritage of the Church should be respected and cherished, because it is the embodiment of centuries of worship and prayer, and an expression of the highest peak of human creativity and spirituality. There was a time when the Church did not run after the latest fashion, but was the maker and arbiter of culture. The lack of commitment to tradition has put the Church and her liturgy on an uncertain and meandering path. The attempted separation of the teaching of Vatican II from previous Church teachings is a dead end, and the only way forward is the hermeneutic of continuity endorsed by Pope Benedict XVI. Recovering the unity, integrity, and harmony of Catholic teaching is the condition for restoring both the liturgy and its music to a noble condition. As Pope Francis taught us in his first encyclical: “Self-knowledge is only possible when we share in a greater memory” (Lumen Fidei 38).

5. Another cause of the decadence of sacred music is clericalism, the abuse of clerical position and status. Clergy who are often poorly educated in the great tradition of sacred music continue to make decisions about personnel and policies that contravene the authentic spirit of the liturgy and the renewal of sacred music repeatedly called for in our times. Often they contradict Vatican II teachings in the name of a supposed “spirit of the Council.” Moreover, especially in countries of ancient Christian heritage, members of the clergy have access to positions that are not available to laity, when there are lay musicians fully capable of offering an equal or superior professional service to the Church.

6. We also see the problem of inadequate (at times, unjust) remuneration of lay musicians. The importance of sacred music in the Catholic liturgy requires that at least some members of the Church in every place be well-educated, well-equipped, and dedicated to serve the People of God in this capacity. Is it not true that we should give to God our best? No one would be surprised or disturbed knowing that doctors need a salary to survive, no one would accept medical treatment from untrained volunteers; priests have their salaries, because they cannot live if they do not eat, and if they do not eat, they will not be able to prepare themselves in theological sciences or to say the Mass with dignity. If we pay florists and cooks who help at parishes, why does it seem so strange that those performing musical activities for the Church would have a right to fair compensation (see Code of Canon Law, can. 231)?

Positive Proposals

It may seem that what we have said is pessimistic, but we maintain the hope that there is a way out of this winter. The following proposals are offered in spiritu humilitatis, with the intention of restoring the dignity of the liturgy and of its music in the Church.

1. As musicians, pastors, scholars, and Catholics who love Gregorian chant and sacred polyphony, so frequently praised and recommended by the Magisterium, we ask for a re-affirmation of this heritage alongside modern sacred compositions in Latin or vernacular languages that take their inspiration from this great tradition; and we ask for concrete steps to promote it everywhere, in every church across the globe, so that all Catholics can sing the praises of God with one voice, one mind and heart, one common culture that transcends all their differences. We also ask for a re-affirmation of the unique importance of the pipe organ for the sacred liturgy, because of its singular capacity to elevate hearts to the Lord and its perfect suitability for supporting the singing of choirs and congregations.

2. It is necessary that the education to good taste in music and liturgy start with children. Often educators without musical training believe that children cannot appreciate the beauty of true art. This is far from the truth. Using a pedagogy that will help them approach the beauty of the liturgy, children will be formed in a way that will fortify their strength, because they will be offered nourishing spiritual bread and not the apparently tasty but unhealthy food of industrial origin (as when “Masses for children” feature pop-inspired music). We notice through personal experience that when children are exposed to these repertoires they come to appreciate them and develop a deeper connection with the Church.

3. If children are to appreciate the beauty of music and art, if they are to understand the importance of the liturgy as fons et culmen [source and apex] of the life of the Church, we must have a strong laity who will follow the Magisterium. We need to give space to well-trained laity in areas that have to do with art and with music. To be able to serve as a competent liturgical musician or educator requires years of study. This “professional” status must be recognized, respected, and promoted in practical ways. In connection with this point, we sincerely hope that the Church will continue to work against obvious and subtle forms of clericalism, so that laity can make their full contribution in areas where ordination is not a requirement.

4. Higher standards for musical repertoire and skill should be insisted on for cathedrals and basilicas. Bishops in every diocese should hire at least a professional music director and/or an organist who would follow clear directions on how to foster excellent liturgical music in that cathedral or basilica and who would offer a shining example of combining works of the great tradition with appropriate new compositions. We think that a sound principle for this is contained in Sacrosanctum Concilium 23: “There must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing.”

5. We suggest that in every basilica and cathedral there be the encouragement of a weekly Mass celebrated in Latin (in either Form of the Roman Rite) so as to maintain the link we have with our liturgical, cultural, artistic, and theological heritage. The fact that many young people today are rediscovering the beauty of Latin in the liturgy is surely a sign of the times, and prompts us to bury the battles of the past and seek a more “catholic” approach that draws upon all the centuries of Catholic worship. With the easy availability of books, booklets, and online resources, it will not be difficult to facilitate the active participation of those who wish to attend liturgies in Latin. Moreover, each parish should be encouraged to have one fully-sung Mass each Sunday.

6. Liturgical and musical training of clergy should be a priority for the Bishops. Clergy have a responsibility to learn and practice their liturgical melodies, since, according to Musicam Sacram and other documents, they should be able to chant the prayers of the liturgy, not merely say the words. In seminaries and at the university, they should come to be familiar with and appreciate the great tradition of sacred music in the Church, in harmony with the Magisterium, and following the sound principle of Matthew 13:52: “Every scribe who has been instructed in the kingdom of heaven is like the head of a household who brings from his storeroom both the new and the old.”

7. In the past, Catholic publishers played a great role in spreading good examples of sacred music, old and new. Today, the same publishers, even if they belong to dioceses or religious institutions, often spread music that is not right for the liturgy, following only commercial considerations. Many faithful Catholics think that what mainstream publishers offer is in line with the doctrine of the Catholic Church regarding liturgy and music, when it is frequently not so. Catholic publishers should have as their first aim that of educating the faithful in sane Catholic doctrine and good liturgical practices, not that of making money.

8. The formation of liturgists is also fundamental. Just as musicians need to understand the essentials of liturgical history and theology, so too must liturgists be educated in Gregorian chant, polyphony, and the entire musical tradition of the Church, so that they may discern between what is good and what is bad.

Conclusion

In his encyclical Lumen Fidei, Pope Francis reminded us of the way faith binds together past and future:

Signed (partial list)

Mº Aurelio Porfiri

Honorary Master and Organist for the Church of Santa Maria dell’Orto, Rome

Publisher of Choralife and Chorabooks, Editor of Altare Dei

Peter A. Kwasniewski, Ph.D.

Professor & Choirmaster

Wyoming Catholic College, WY, USA

Most Rev. Athanasius Schneider

Auxiliary Bishop of Astana

President of the Liturgical Commission of the Conference of the Catholic Bishops of Kazakhstan

The Most Reverend Rene Henry Gracida, D.D.

Bishop Emeritus of Corpus Christi

Abbot Philip Anderson

Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey

Hulbert, Oklahoma, USA

Rev. Prof. Nicola Bux

Priest, Archdiocese of Bari

Professor of Eastern Liturgy and Sacramental Theology

Sir James MacMillan C.B.E.

Composer and conductor

Peter Phillips

Founder and Director of the Tallis Scholars

Publisher of the Musical Times

Bodley Fellow, Merton College, Oxford

Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

Colin Mawby, K.S.G.

Liturgical Composer and Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral 1961–1977

Kevin Allen

Composer

Chicago, IL, USA

Frank J. La Rocca, Ph.D.

Composer

Emeritus Professor of Music, Oakland, California, USA

M° Giorgio Carnini

Organista, compositore e direttore d’orchestra

Presidente Associazione Camerata Italica

Direttore artistico del festival e progetto “Un organo per Roma”

Buenos Aires; Roma

Prof. Giancarlo Rostirolla

Musicologo, Ricercatore, Accademico

Presidente dell’Istituto di Bibliografia Musicale

Direttore Artistico della Fondazione Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

William Peter Mahrt, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University, Stanford, California

President, Church Music Association of America

Such love and practice of music is witnessed to throughout Christian literature and in the many documents that the Popes have devoted to sacred music, from John XXII’s Docta Sanctorum Patrum (1324) and Benedict XIV’s Annus Qui (1749) down to Saint Pius X’s Motu Proprio Tra le Sollecitudini (1903), Pius XII’s Musicae Sacrae Disciplina (1955), Saint John Paul II’s Chirograph on Sacred Music (2003), and so on. This vast amount of documentation impels us to take with utter seriousness the importance and the role of music in the liturgy. This importance is related to the deep connection between the liturgy and its music, a connection that goes two ways: a good liturgy allows for splendid music, but a low standard of liturgical music also tremendously affects the liturgy. Nor can the ecumenical importance of music be forgotten, when we know that other Christian traditions — such as Anglicans, Lutherans, and the Eastern Orthodox — have high esteem for the importance and dignity of sacred music, as witnessed by their own jealously-guarded “treasuries.”

We are observing an important milestone, the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of the Instruction on Music in the Liturgy, Musicam Sacram, on March 5, 1967, under the pontificate of Blessed Paul VI. Re-reading the document today, we cannot avoid thinking of the via dolorosa of sacred music in the decades following Sacrosanctum Concilium. Indeed, what was happening in some factions of the Church at that time (1967) was not at all in line with Sacrosantum Concilium or with Musicam Sacram. Certain ideas that were never present in the Council’s documents were forced into practice, sometimes with a lack of vigilance from clergy and ecclesiastical hierarchy. In some countries the treasury of sacred music that the Council asked to be preserved was not only not preserved, but even opposed. And this quite against the Council, which clearly stated:

The musical tradition of the universal Church is a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art. The main reason for this pre-eminence is that, as sacred song united to the words, it forms a necessary or integral part of the solemn liturgy. Holy Scripture, indeed, has bestowed praise upon sacred song, and the same may be said of the fathers of the Church and of the Roman pontiffs who in recent times, led by St. Pius X, have explained more precisely the ministerial function supplied by sacred music in the service of the Lord. Therefore sacred music is to be considered the more holy in proportion as it is more closely connected with the liturgical action, whether it adds delight to prayer, fosters unity of minds, or confers greater solemnity upon the sacred rites. But the Church approves of all forms of true art having the needed qualities, and admits them into divine worship. (SC 112)

The Current Situation

In light of the mind of the Church so frequently expressed, we cannot avoid being concerned about the current situation of sacred music, which is nothing short of desperate, with abuses in the area of sacred music now almost the norm rather than the exception. We shall summarize here some of the elements that contribute to the present deplorable situation of sacred music and of the liturgy.

1. There has been a loss of understanding of the “musical shape of the liturgy,” that is, that music is an inherent part of the very essence of liturgy as public, formal, solemn worship of God. We are not merely to sing at Mass, but to sing the Mass. Hence, as Musicam Sacram itself reminded us, the priest’s parts should be chanted to the tones given in the Missal, with the people making the responses; the singing of the Ordinary of the Mass in Gregorian chant or music inspired by it should be encouraged; and the Propers of the Mass, too, should be given the pride of place that befits their historical prominence, their liturgical function, and their theological depth. Similar points apply to the singing of the Divine Office. It is an exhibition of the vice of “liturgical sloth” to refuse to sing the liturgy, to use “utility music” rather than sacred music, to refuse to educate oneself or others about the Church’s tradition and wishes, and to put little or no effort and resources into the building up of a sacred music program.

2. This loss of liturgical and theological understanding goes hand-in-hand with an embrace of secularism. The secularism of popular musical styles has contributed to a desacralization of the liturgy, while the secularism of profit-based commercialism has reinforced the imposition of mediocre collections of music upon parishes. It has encouraged an anthropocentrism in the liturgy that undermines its very nature. In vast sectors of the Church nowadays there is an incorrect relationship with culture, which can be seen as a “web of connections.” With the actual situation of our liturgical music (and of the liturgy itself, because the two are intertwined), we have broken this web of connection with our past and tried to connect with a future that has no meaning without its past. Today, the Church is not actively using her cultural riches to evangelize, but is mostly used by a prevalent secular culture, born in opposition to Christianity, which destabilizes the sense of adoration that is at the heart of the Christian faith.

In his homily for the feast of Corpus Christi on June 4, 2015, Pope Francis has spoken of “the Church’s amazement at this reality [of the Most Holy Eucharist]. . . An astonishment which always feeds contemplation, adoration, and memory.” In many of our Churches around the world, where is this sense of contemplation, this adoration, this astonishment for the mystery of the Eucharist? It is lost because we are living a sort of spiritual Alzheimer’s, a disease that is taking our spiritual, theological, artistic, musical and cultural memories away from us. It has been said that we need to bring the culture of every people into the liturgy. This may be right if correctly understood, but not in the sense that the liturgy (and the music) becomes the place where we have to exalt a secular culture. It is the place where the culture, every culture, is brought to another level and purified.

3. There are groups in the Church that push for a “renewal” that does not reflect Church teaching but rather serves their own agenda, worldview, and interests. These groups have members in key leadership positions from which they put into practice their plans, their idea of culture, and the way we have to deal with contemporary issues. In some countries powerful lobbies have contributed to the de facto replacement of liturgical repertoires faithful to the directives of Vatican II with low-quality repertoires. Thus, we end up with repertoires of new liturgical music of very low standards as regards both the text and the music. This is understandable when we reflect that nothing of lasting worth can come from a lack of training and expertise, especially when people neglect the wise precepts of Church tradition:

On these grounds Gregorian Chant has always been regarded as the supreme model for sacred music, so that it is fully legitimate to lay down the following rule: the more closely a composition for church approaches in its movement, inspiration and savor the Gregorian form, the more sacred and liturgical it becomes; and the more out of harmony it is with that supreme model, the less worthy it is of the temple. (St. Pius X, Motu Proprio Tra le Sollecitudini)Today this “supreme model” is often discarded, if not despised. The entire Magisterium of the Church has reminded us of the importance of adhering to this important model, not as way of limiting creativity but as a foundation on which inspiration can flourish. If we desire that people look for Jesus, we need to prepare the house with the best that the Church can offer. We will not invite people to our house, the Church, to give them a by-product of music and art, when they can find a much better pop music style outside the Church. Liturgy is a limen, a threshold that allows us to step from our daily existence to the worship of the angels: Et ídeo cum Angelis et Archángelis, cum Thronis et Dominatiónibus, cumque omni milítia cæléstis exércitus, hymnum glóriæ tuæ cánimus, sine fine dicéntes...

4. This disdain for Gregorian chant and traditional repertoires is one sign of a much bigger problem, that of disdain for Tradition. Sacrosanctum Concilium teaches that the musical and artistic heritage of the Church should be respected and cherished, because it is the embodiment of centuries of worship and prayer, and an expression of the highest peak of human creativity and spirituality. There was a time when the Church did not run after the latest fashion, but was the maker and arbiter of culture. The lack of commitment to tradition has put the Church and her liturgy on an uncertain and meandering path. The attempted separation of the teaching of Vatican II from previous Church teachings is a dead end, and the only way forward is the hermeneutic of continuity endorsed by Pope Benedict XVI. Recovering the unity, integrity, and harmony of Catholic teaching is the condition for restoring both the liturgy and its music to a noble condition. As Pope Francis taught us in his first encyclical: “Self-knowledge is only possible when we share in a greater memory” (Lumen Fidei 38).

5. Another cause of the decadence of sacred music is clericalism, the abuse of clerical position and status. Clergy who are often poorly educated in the great tradition of sacred music continue to make decisions about personnel and policies that contravene the authentic spirit of the liturgy and the renewal of sacred music repeatedly called for in our times. Often they contradict Vatican II teachings in the name of a supposed “spirit of the Council.” Moreover, especially in countries of ancient Christian heritage, members of the clergy have access to positions that are not available to laity, when there are lay musicians fully capable of offering an equal or superior professional service to the Church.

6. We also see the problem of inadequate (at times, unjust) remuneration of lay musicians. The importance of sacred music in the Catholic liturgy requires that at least some members of the Church in every place be well-educated, well-equipped, and dedicated to serve the People of God in this capacity. Is it not true that we should give to God our best? No one would be surprised or disturbed knowing that doctors need a salary to survive, no one would accept medical treatment from untrained volunteers; priests have their salaries, because they cannot live if they do not eat, and if they do not eat, they will not be able to prepare themselves in theological sciences or to say the Mass with dignity. If we pay florists and cooks who help at parishes, why does it seem so strange that those performing musical activities for the Church would have a right to fair compensation (see Code of Canon Law, can. 231)?

Positive Proposals

It may seem that what we have said is pessimistic, but we maintain the hope that there is a way out of this winter. The following proposals are offered in spiritu humilitatis, with the intention of restoring the dignity of the liturgy and of its music in the Church.

1. As musicians, pastors, scholars, and Catholics who love Gregorian chant and sacred polyphony, so frequently praised and recommended by the Magisterium, we ask for a re-affirmation of this heritage alongside modern sacred compositions in Latin or vernacular languages that take their inspiration from this great tradition; and we ask for concrete steps to promote it everywhere, in every church across the globe, so that all Catholics can sing the praises of God with one voice, one mind and heart, one common culture that transcends all their differences. We also ask for a re-affirmation of the unique importance of the pipe organ for the sacred liturgy, because of its singular capacity to elevate hearts to the Lord and its perfect suitability for supporting the singing of choirs and congregations.

2. It is necessary that the education to good taste in music and liturgy start with children. Often educators without musical training believe that children cannot appreciate the beauty of true art. This is far from the truth. Using a pedagogy that will help them approach the beauty of the liturgy, children will be formed in a way that will fortify their strength, because they will be offered nourishing spiritual bread and not the apparently tasty but unhealthy food of industrial origin (as when “Masses for children” feature pop-inspired music). We notice through personal experience that when children are exposed to these repertoires they come to appreciate them and develop a deeper connection with the Church.

3. If children are to appreciate the beauty of music and art, if they are to understand the importance of the liturgy as fons et culmen [source and apex] of the life of the Church, we must have a strong laity who will follow the Magisterium. We need to give space to well-trained laity in areas that have to do with art and with music. To be able to serve as a competent liturgical musician or educator requires years of study. This “professional” status must be recognized, respected, and promoted in practical ways. In connection with this point, we sincerely hope that the Church will continue to work against obvious and subtle forms of clericalism, so that laity can make their full contribution in areas where ordination is not a requirement.

4. Higher standards for musical repertoire and skill should be insisted on for cathedrals and basilicas. Bishops in every diocese should hire at least a professional music director and/or an organist who would follow clear directions on how to foster excellent liturgical music in that cathedral or basilica and who would offer a shining example of combining works of the great tradition with appropriate new compositions. We think that a sound principle for this is contained in Sacrosanctum Concilium 23: “There must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing.”

5. We suggest that in every basilica and cathedral there be the encouragement of a weekly Mass celebrated in Latin (in either Form of the Roman Rite) so as to maintain the link we have with our liturgical, cultural, artistic, and theological heritage. The fact that many young people today are rediscovering the beauty of Latin in the liturgy is surely a sign of the times, and prompts us to bury the battles of the past and seek a more “catholic” approach that draws upon all the centuries of Catholic worship. With the easy availability of books, booklets, and online resources, it will not be difficult to facilitate the active participation of those who wish to attend liturgies in Latin. Moreover, each parish should be encouraged to have one fully-sung Mass each Sunday.

6. Liturgical and musical training of clergy should be a priority for the Bishops. Clergy have a responsibility to learn and practice their liturgical melodies, since, according to Musicam Sacram and other documents, they should be able to chant the prayers of the liturgy, not merely say the words. In seminaries and at the university, they should come to be familiar with and appreciate the great tradition of sacred music in the Church, in harmony with the Magisterium, and following the sound principle of Matthew 13:52: “Every scribe who has been instructed in the kingdom of heaven is like the head of a household who brings from his storeroom both the new and the old.”

7. In the past, Catholic publishers played a great role in spreading good examples of sacred music, old and new. Today, the same publishers, even if they belong to dioceses or religious institutions, often spread music that is not right for the liturgy, following only commercial considerations. Many faithful Catholics think that what mainstream publishers offer is in line with the doctrine of the Catholic Church regarding liturgy and music, when it is frequently not so. Catholic publishers should have as their first aim that of educating the faithful in sane Catholic doctrine and good liturgical practices, not that of making money.

8. The formation of liturgists is also fundamental. Just as musicians need to understand the essentials of liturgical history and theology, so too must liturgists be educated in Gregorian chant, polyphony, and the entire musical tradition of the Church, so that they may discern between what is good and what is bad.

Conclusion

In his encyclical Lumen Fidei, Pope Francis reminded us of the way faith binds together past and future:

As a response to a word which preceded it, Abraham’s faith would always be an act of remembrance. Yet this remembrance is not fixed on past events but, as the memory of a promise, it becomes capable of opening up the future, shedding light on the path to be taken. We see how faith, as remembrance of the future, memoria futuri, is thus closely bound up with hope. (LF 9)This remembrance, this memory, this treasure that is our Catholic tradition is not something of the past alone. It is still a vital force in the present, and will always be a gift of beauty to future generations. “Sing praises to the Lord, for he has done gloriously; let this be known in all the earth. Shout, and sing for joy, O inhabitant of Zion, for great in your midst is the Holy One of Israel” (Is 12:5–6).

Signed (partial list)

Mº Aurelio Porfiri

Honorary Master and Organist for the Church of Santa Maria dell’Orto, Rome

Publisher of Choralife and Chorabooks, Editor of Altare Dei

Peter A. Kwasniewski, Ph.D.

Professor & Choirmaster

Wyoming Catholic College, WY, USA

Most Rev. Athanasius Schneider

Auxiliary Bishop of Astana

President of the Liturgical Commission of the Conference of the Catholic Bishops of Kazakhstan

The Most Reverend Rene Henry Gracida, D.D.

Bishop Emeritus of Corpus Christi

Abbot Philip Anderson

Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey

Hulbert, Oklahoma, USA

Rev. Prof. Nicola Bux

Priest, Archdiocese of Bari

Professor of Eastern Liturgy and Sacramental Theology

Sir James MacMillan C.B.E.

Composer and conductor

Peter Phillips

Founder and Director of the Tallis Scholars

Publisher of the Musical Times

Bodley Fellow, Merton College, Oxford

Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

Colin Mawby, K.S.G.

Liturgical Composer and Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral 1961–1977

Kevin Allen

Composer

Chicago, IL, USA

Frank J. La Rocca, Ph.D.

Composer

Emeritus Professor of Music, Oakland, California, USA

M° Giorgio Carnini

Organista, compositore e direttore d’orchestra

Presidente Associazione Camerata Italica

Direttore artistico del festival e progetto “Un organo per Roma”

Buenos Aires; Roma

Prof. Giancarlo Rostirolla

Musicologo, Ricercatore, Accademico

Presidente dell’Istituto di Bibliografia Musicale

Direttore Artistico della Fondazione Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

William Peter Mahrt, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University, Stanford, California

President, Church Music Association of America

David W. Fagerberg

Professor, Department of Theology

University of Notre Dame

Dr. Joseph Shaw

Senior Research Fellow, St Benet’s Hall, Oxford University

President of the Latin Mass Society of England & Wales

Martin Mosebach

German novelist & essayist

Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Roberto Spataro

Docente ordinario Università Pontificia Salesiana

Segretario della Pontificia Academia Latinitatis

Dottor Ettore Gotti Tedeschi

Economista e banchiere

Prof. Dr. Massimo de Leonardis

Ordinario di Storia delle relazioni internazionali

Direttore del Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

Milano – Italia

Rev. George William Rutler, M. St. (Oxon.), S.T.D., LL.D.

Pastor, Church of Saint Michael

New York City, New York

Rev. Brian W. Harrison, OS, MA, STD

Associate Professor of Theology (retired), Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico

Chaplain, St. Mary of Victories Chapel,

St. Louis, Missouri, USA

Rev. Thomas M. Kocik

Parish Priest, Fall River, Mass., USA

Past Editor, Antiphon: A Journal for Liturgical Renewal

Rev. Richard G. Cipolla

Pastor, St. Mary’s Church

Norwalk, CT

Rev. James V. Schall, S.J.

Professor Emeritus

Georgetown University

Washington, DC, USA

Prof. Pier Paolo Donati

Direttore di “Informazione Organistica”

Già docente di Storia della Musica all’Università di Firenze

Rev. John Zuhlsdorf

Madison, WI, USA

Vytautas Miskinis

Composer, Conductor, Professor

Artistic Director of Boy’s and Male Choir AZUOLIUKAS

Professor of Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre

President of Lithuanian Choral Union

Wilko Brouwers

Utrecht Center for the Arts

Gregorian Circle Utrecht

Scott Turkington

Director of Sacred Music

Holy Family Church & Holy Family Academy

Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

Jeffrey Morse

Schola Gregoriana of Cambridge

Rev. J. W. Hunwicke

Priest of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham

sometime Head of Theology, Lancing College

formerly Senior Research Fellow, Pusey House, Oxford

Right Reverend Archimandrite John A. Mangels

St. Augustine Antiochian Orthodox Christian Church, Denver CO, USA

Founder of the Ambrosian Choristers

Professor, Department of Theology

University of Notre Dame

Dr. Joseph Shaw

Senior Research Fellow, St Benet’s Hall, Oxford University

President of the Latin Mass Society of England & Wales

Martin Mosebach

German novelist & essayist

Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Roberto Spataro

Docente ordinario Università Pontificia Salesiana

Segretario della Pontificia Academia Latinitatis

Dottor Ettore Gotti Tedeschi

Economista e banchiere

Prof. Dr. Massimo de Leonardis

Ordinario di Storia delle relazioni internazionali

Direttore del Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

Milano – Italia

Rev. George William Rutler, M. St. (Oxon.), S.T.D., LL.D.

Pastor, Church of Saint Michael

New York City, New York

Rev. Brian W. Harrison, OS, MA, STD

Associate Professor of Theology (retired), Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico

Chaplain, St. Mary of Victories Chapel,

St. Louis, Missouri, USA

Rev. Thomas M. Kocik

Parish Priest, Fall River, Mass., USA

Past Editor, Antiphon: A Journal for Liturgical Renewal

Rev. Richard G. Cipolla

Pastor, St. Mary’s Church

Norwalk, CT

Rev. James V. Schall, S.J.

Professor Emeritus

Georgetown University

Washington, DC, USA

Prof. Pier Paolo Donati

Direttore di “Informazione Organistica”

Già docente di Storia della Musica all’Università di Firenze

Rev. John Zuhlsdorf

Madison, WI, USA

Vytautas Miskinis

Composer, Conductor, Professor

Artistic Director of Boy’s and Male Choir AZUOLIUKAS

Professor of Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre

President of Lithuanian Choral Union

Wilko Brouwers

Utrecht Center for the Arts

Gregorian Circle Utrecht

Scott Turkington

Director of Sacred Music

Holy Family Church & Holy Family Academy

Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

Jeffrey Morse

Schola Gregoriana of Cambridge

Rev. J. W. Hunwicke

Priest of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham

sometime Head of Theology, Lancing College

formerly Senior Research Fellow, Pusey House, Oxford

Right Reverend Archimandrite John A. Mangels

St. Augustine Antiochian Orthodox Christian Church, Denver CO, USA

Founder of the Ambrosian Choristers

Christopher Mueller

Founder & President

Christopher Mueller Foundation for Polyphony & Chant

Massimo Lapponi O.S.B.

Monaco sacerdote professo dell’Abbazia Benedettina di Farfa

già docente di Etica e Filosofia della Religione presso il Pont. Ateneo di Sant’Anselmo

Patrick Banken

President of Una Voce France

Vice President of the International Federation Una Voce

(The full list of over 200 signatories is available here.)

Founder & President

Christopher Mueller Foundation for Polyphony & Chant

Massimo Lapponi O.S.B.

Monaco sacerdote professo dell’Abbazia Benedettina di Farfa

già docente di Etica e Filosofia della Religione presso il Pont. Ateneo di Sant’Anselmo

Patrick Banken

President of Una Voce France

Vice President of the International Federation Una Voce

(The full list of over 200 signatories is available here.)

↧

↧

In Honor of St. Thomas Aquinas: A Portion of St. Francis Borgia’s “Litany of the Attributes of God”

On the eve of the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas, recalling the very day of his passing from this life to life eternal (March 7, 1274), I would like to share with readers a translation of a curious little piece in the vast history of scholasticism and Counter-reformation piety.

Years ago, Fr. John Saward placed in my hands a remarkable little book written by St. Francis Borgia. It turned out to be a detailed litany, or rather, a series of litanies, modeled after and drawn from the text of the Summa theologiae of St. Thomas Aquinas. Apparently, Borgia, to prevent the study of Aquinas from becoming abstract and bloodless, decided to turn every article into a prayer. The result is intriguing. While I would not claim that these litanies ought to be introduced into the public worship of the Church, they do remind us that the ultimate goal of theology is union with God, whose praises we sing by inquiry into the truth. The right use of the intellect to ponder the truth is pleasing to God and can be offered to him as incense of the spirit.

Below is translated the litany that is based on the first treatise of the Prima Pars, namely, of the existence and attributes of God. The slim volume from which I translated it furnishes litanies similar to this one for every major treatise in the Summa.

Years ago, Fr. John Saward placed in my hands a remarkable little book written by St. Francis Borgia. It turned out to be a detailed litany, or rather, a series of litanies, modeled after and drawn from the text of the Summa theologiae of St. Thomas Aquinas. Apparently, Borgia, to prevent the study of Aquinas from becoming abstract and bloodless, decided to turn every article into a prayer. The result is intriguing. While I would not claim that these litanies ought to be introduced into the public worship of the Church, they do remind us that the ultimate goal of theology is union with God, whose praises we sing by inquiry into the truth. The right use of the intellect to ponder the truth is pleasing to God and can be offered to him as incense of the spirit.

Below is translated the litany that is based on the first treatise of the Prima Pars, namely, of the existence and attributes of God. The slim volume from which I translated it furnishes litanies similar to this one for every major treatise in the Summa.

St. Francis Borgia

LITANY

of the attributes of God taken from the Prima Pars of St. Thomas (qq. 1–26)

LITANY

of the attributes of God taken from the Prima Pars of St. Thomas (qq. 1–26)

| O highest God, whom no one save Thyself can perfectly know, | have mercy on us. | ||

| q. 1 a. 1 | Thou, who art the subject of theology, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | Thou, who in Thyself art unknown to us, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 2 a. 1 | Thou, whose existence as God is perfectly demonstrable, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, who art, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | O incorporeal God, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 3 aa.1,2 | Thou, in whom is no composition of matter and form, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 5 | Thou, who art Thy existence and Thy divinity, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | Thou, who art Thy existence and Thy essence, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 5 | Thou, who art in no genus, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | Thou, in whom is no accident, | have mercy on us. | |

| O God, wholly simple, | have mercy on us. | ||

| a. 7 | Thou, who are commingled in composition with no others, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 4 a. 1 | O perfect God, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, O God, who contain in Thyself most eminently the perfections of all things, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 5 a. 2 | O highest Good, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who art good through Thy own essence, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 7 a. 1 | O infinite God, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 8 a. 1 | O God, existing in all things, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | O God, who art everywhere, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | O God, who art everywhere by essence, presence, and power, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, to whom alone it belongs to be everywhere, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 9 a. 1 | O changeless God, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | O God, to whom alone it belongs to be changeless, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 10 a. 2 | O eternal God, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | O God, to whom alone it belongs to be simply eternal, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 11 a. 1 | Thou, who art one God, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who art one in the highest way, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 12 a. 3 | O divine essence, whom the bodily eye does not see, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O divine essence, whom the created intellect cannot see by its natural powers, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 5 | O divine essence, the vision of whom demands a created light, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | O divine essence, seen more perfectly by the more perfect, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | O divine essence, incomprehensible to its beholders, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 9 | O divine essence, through whom all things that the blessed see are not gazed upon through any likenesses, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 10 | O divine essence, in whom all that the blessed see is known at once, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 12 | O divine essence, of whom grace gives a higher knowledge than natural reason, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 13 a. 1 | All-powerful God, whom we name in order to know, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | O God, of whom all names are said substantially, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | O God, whose names are truly applied according to that which they signify, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 5 | O God, whose names with respect to creatures are said by way of analogy, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | O God, of whom this name, god, is the name of Thy nature, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | O God, whose name is incommunicable, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 8 | O God, to whom this name, he who is, is most proper of all, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 14 a. 1 | O God, the height of riches, of wisdom, and of knowledge, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, who art known to Thyself through Thyself, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who comprehend Thyself, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, whose knowing is Thy very substance, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | Thou, who know things other than Thee by proper knowledge, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | O God, whose knowledge is not discursive, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 8 | O God, whose knowledge coupled with will is the cause of things, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 9 | Thou, who have knowledge of non-being, of things called ‘those which are not,’ | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 10 | O God, who know evil things by knowing good things, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 11 | Thou, who know each and every particular, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 12 | O God, who know the infinite, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 13 | O God, whose knowledge extends to future contingents, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 15 | O God, whose knowledge is unvarying, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 16 | Thou, who have a gazing knowledge of things, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 15 a. 1 | Thou, who have ideas of all good things, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 16 a. 5 | Thou, who art the highest truth, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | Thou, who art the one only truth according to which all things are true, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | Thou, who art eternal truth, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 8 | Thou, who art unchanging truth, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 18 a. 3 | O God, in whom is the highest and most perfect life, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, in whom all things are the same divine life, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 19 a. 1 | O God, in whom is will, by which Thou lovest Thyself, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, who will even things other than Thee through Thy will, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who dost not will of necessity the things which are created by Thee, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, whose will is the cause of things, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 5 | O God, for whose will no efficient cause can be assigned, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | O God, whose will is always accomplished, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | O God, whose will is unchanging, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 8 | O God, whose will does not impose necessity upon free will, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 20 a. 1 | O God, in whom is love, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, who love all that Thou hast made, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who love all with one simple act of will, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | Thou, who love more the better things, in that Thou willest a greater good to them, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 21 a. 1 | O God, in whom is a justice that grants all things their due, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, who art justice and truth, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who art merciful and compassionate, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, in all of whose works are found mercy and justice, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 22 a. 1 | Thou, who govern all things by providence, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | O God, to whose providence all things are subjected, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who provide immediately for all things, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, who by Thy providence do not impose necessity upon the free, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 23 a. 1 | O God, by whom are predestined those who are chosen, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | O God, in whose mind predestination is the reason for the ordering of some to eternal salvation, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | O God, who cast off some by permitting them to fall away, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | O God, who choose the predestined, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 5 | O God, who save us according to Thy mercy and not from our works of justice, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 6 | O God, whose predestination is unfailing, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 7 | O God, who foreknow the exact number of the predestined, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 24 a. 2 | O God, whose conscription, which firmly retains those who are predestined to eternal life, is the Book of Life, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | O God, by falling away from whose grace those abounding in present justice are said to be blotted from the Book of Life, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 25 a. 3 | Thou, who can do all things more abundantly than we seek or understand, | have mercy on us. | |

| q. 26 a. 1 | O God, to whom blessedness belongs, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 2 | Thou, who art blessed according to intellect, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 3 | Thou, who, as object, art the very blessedness of the saints, | have mercy on us. | |

| a. 4 | Thou, who enfold all happiness in Thy divine blessedness, | have mercy on us. | |

| Prayers that follow | |||

| From those who say that God is the soul of the world, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From those who say that God is the formal principle of all things, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From David of Dinant, asserting that God is prime matter, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From asserting that an infinite body is the principle of things, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From saying that God does not know things other than Himself except in what they have in common, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From those who say that God does not know singulars except by applying universal causes to particular effects, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From those who say that God creates nothing other than the first creature, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From the vanity of philosophers who attribute contingent effects to secondary causes alone, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From the Epicureans who maintain that the world came to be by chance, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From those who maintain that only incorruptible things are subject to divine providence, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From those who attribute to man the beginning of good works, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| From those who say that divine predestination can be changed by prayers, | deliver us, O Lord. | ||

| That theological study may inflame our hearts, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That through tracing effects we may arrive at the first cause, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That contemplating the divine simplicity, we may imitate it in simple hearts, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That full of praise we may admire the abyss of divine goodness, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may know God even as we are known, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may name Him with fear and trembling, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That the divine essence may enlighten us, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That loving the highest truth we may merit that the same truth will free us, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may live for Him who is our life, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may love Him who first loved us, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may follow the traces of divine mercy, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may contemplate divine providence, giving thanks in everything to God, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That He who predestines us to the adoption of sons may not see us ungrateful, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may be humbled in our knowledge by dwelling on the power of God, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| That we may enjoy the God who is our blessedness, | We beseech Thee, hear us. | ||

| V. What god is like unto our God for greatness? | |||

| R. Thou who alone dost wonders. | |||

| PRAYER. | |||

| Look upon our weakness, O God, and make us not to grow faint in the praises of Thy attributes; that as Thou eternally takest delight in them without beginning, so we too, having been made partakers in them by rejoicing with Thee, may merit to praise them endlessly with Thy angels, for worthy is the Lamb that was slain, to receive wisdom, glory, and blessing, for ever and ever, Amen. | |||

↧

Melkite Bishop Nicholas to Celebrate Divine Liturgy on Berkeley Campus, March 11th

The third in the series of monthly liturgies of the Melkite Outreach of Berkeley will be held on Satruday, March 11th, 5pm, at the Gesu Chapel of the Jesuit School of Theology, 1735 Leroy Ave., Berkeley.

The liturgy is usually celebrated by Fr Christopher Hadley, who teaches at the Jesuit School; Fr Sebastian Carnazzo, pastor of St Elias Melkite Church in Los Gatos, California, has told me “This time we will be honored to host his Grace, Nicholas Samra, bishop of the Melkite Diocese of the United States, who will be celebrating the Divine Liturgy and giving us his episcopal blessing and exhortation.”

Hope to see you there.

Here is a recording of the Hymn of Lent: Open to Me the Gates of Repentance

The Divine Liturgy will be that of Sunday, March 12th, which is the Sunday of St Gregory Palamas in the Byzantine Rite.

Years ago, I was told of a difference between East and West in the interpretation of the Transfiguration. St Thomas Aquinas stated that Christ changed when he shone with light, and this was an anticipation of the beatific vision. St Gregory Palamas, on the other hand, argued that the Apostles changed spiritually and they were able, temporarily, to see the uncreated light of Christ - their climbing of the mountain was a metaphor for their spiritual upwards movement towards a greater purity in heart. Through the sacramental life of the Church, it is possible for all of us to grow by degrees in purity and be transformed, so that we can both witness and shine with the uncreated light of Christ. As Our Lord told us, blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

I once raised this point, which I thought was a contradiction, with a Benedictine monk at Pluscarden Abbey in Scotland. He told me that I should “think liturgically,” and suggested that these two interpretations were not mutually exclusive. There might be a dual motion taking place in some way, so that just as God comes down to us, so to speak, as Christ is present in the Eucharist, so in taking communion we are supernaturally transformed and so are raised up to meet Him.

The liturgy is usually celebrated by Fr Christopher Hadley, who teaches at the Jesuit School; Fr Sebastian Carnazzo, pastor of St Elias Melkite Church in Los Gatos, California, has told me “This time we will be honored to host his Grace, Nicholas Samra, bishop of the Melkite Diocese of the United States, who will be celebrating the Divine Liturgy and giving us his episcopal blessing and exhortation.”

Hope to see you there.

Here is a recording of the Hymn of Lent: Open to Me the Gates of Repentance

The Divine Liturgy will be that of Sunday, March 12th, which is the Sunday of St Gregory Palamas in the Byzantine Rite.