Matthew P Hazell & Dr. Peter A Kwasniewski (Foreword),

(Lectionary Study Press, 2016.

The creation of a new form of the Mass was the single most dramatic change to Roman Catholic life out of all the many changes that followed the Second Vatican Council. Pope Paul VI’s Apostolic Constitution, Missale Romanum, which was published in 1969, along with the subsequent publication of the new missal with the same name in 1970, altered the Mass in many ways. One of the most significant differences between the Mass of 1969 (which is now called the Ordinary Form) [1], and the Mass according to the Missale Romanum of 1962 (which is now called the Extraordinary Form) was the introduction of many more Scripture readings along with many changes to where and how much of the previously included readings were used in the liturgy of the Mass.

One unexpected and disquieting thing that becomes obvious when you take a close look at the tables in Index Lectionum, which compare the two sets of Mass readings, is how much Scripture was removed from the new Mass, even though the stated goal was to include more Scripture.

Let’s start with some of the history and stated motives behind the revisions to the Scriptures read in Masses during the liturgical year. Later on, this article gives an example of the consequences of one notable omission of verses that are doctrinally important: verses 27-32 of 1 Corinthians 11 no longer appear in the New Mass lectionary at any time during the year, even though these verses are essential for understanding why the Church prohibits Catholics in an illicit marriage from receiving Communion and why the doctrine should not be changed.

Paul VI and Sacred Scripture in the Mass

Blessed Pope Paul VI was a strong proponent of including more Scripture in the Mass. “Paul VI exhibited a long and consistent record, dating from the years prior to his election to the See of Peter, of promoting, encouraging, and emphasizing at every opportunity the value of the greatly extended use of Sacred Scripture that became such a major feature of the post-conciliar liturgical reform. Indeed, it seems clear that, in his mind, this was the most important and valuable single feature of the reform.”[2]

Before the council ended, and within a few months after Pope Paul VI’s election, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), was released as the council’s first document. The readings used at Masses were changed based four sections of SC: 24, 35, 51, 92. The most frequently quoted section in support of this change is number 35. § 35: In the sacred rites, a more abundant, more varied, and more appropriate selection of readings from Sacred Scripture is to be restored.[3]

In 1964, Pope Paul VI established the

Consilium ad exsequendam Constitutionem de Sacra Liturgia, the council for implementing the constitution on the liturgy. Part of the consilium’s assigned task was to create a new lectionary. [4]

The consilium expanded the lectionary from a single-year cycle to a three-year cycle for Sundays and a two-year cycle for weekdays. The Latin edition of the lectionary was published in 1969, the English edition for the USA in 1970; use of the revised lectionary[5] and the revised Roman Missal began on the First Sunday of Advent: November 30, 1970.

For Sundays and major feast days, each yearly cycle begins on the first Sunday of Advent (the last Sunday of November or first Sunday of December). In the new lectionary, the readings for each of the three years of the A, B, C cycle for Sundays are mostly taken from the Synoptic Gospels. Matthew’s Gospel was assigned to year A, Mark’s to year B, and Luke’s to year C.

• Year A: Gospel of Matthew (November 2013 through 2014)

• Year B: Gospel of Mark (December 2014 through 2015)

• Year C: Gospel of Luke (December 2015 through 2016)

Readings from the Gospel of John are assigned during Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide during every year. (For more about the changes to which Johanine verses are used when, see an interesting discussion in Dr. Peter Kwasniewski’s Foreword to the

Index Lectionum.)

For Sundays and feast days, a third reading was added before the Epistle and Gospel, which is taken from the Old Testament except during Eastertide, when the third readings is taken from the Acts of the Apostles. On ordinary weekdays, readings are taken from the remaining parts of the Bible.

For weekdays, odd-numbered years use the readings for Cycle I; even-numbered years are Cycle II.

A Responsorial Psalm [6] was also added between the Epistle and Gospel.

Overview of the Changes

“The Catholic Lectionary” website by Father Felix Just, S.J., is one useful resource for learning more about the lectionaries before and after the Second Vatican Council. The following summary of the differences between the two lectionaries for the Extraordinary and Ordinary Form is based on the “Historical Overview” page found at

Fr. Just’s website. [7]

Extraordinary Form Lectionary

Roman Missal / Missale Romanum (various pre-Vatican II editions, based on the Missal of Pope Pius V from 1570)

• The same readings are read each year on the Sundays and feast days.

• Most Masses had only two readings: the Epistle and the Gospel.

• Parts of the Old Testament were read only on a few feasts, vigils, ember days, and within some liturgical octaves.

• Most weekday Masses did not have their own assigned readings (Propers). On feast days, the readings were from the feast. Otherwise, the readings were usually from the prior Sunday.

• The biblical texts used for Sundays, vigils, and major feasts include about 22% of the NT Gospels, 11% of the NT Epistles, and only 0.8% of the OT (not counting the Psalms).

Ordinary Form Lectionary

Lectionary for Mass (first and second edition after the Second Vatican Council, 1963)

• A greater variety of readings is included in a three-year cycle for Sundays (A/B/C) and a two-year cycle (I/II) for weekdays.

• Three main readings are now prescribed for Sundays and major feasts: Reading 1, usually from OT books; Reading 2, from NT Epistles; Reading 3, from NT Gospels.

• The biblical texts used for Sundays, vigils, and major feasts now include about 58% of the NT Gospels, 25% of the NT Epistles, but still only 3.7% of the OT (not counting the Psalms).

• Including all the Masses for Sundays, weekdays, rituals, votives, the propers and commons of saints, and special needs and occasions, the

Lectionary for Mass now covers much of the NT (about 90% of the Gospels, 55% of the rest: Acts, Epistles, Revelation), but still very little of the OT (slightly over 13%).

One commentator noted, “It is interesting to know that only 13.5% of the OT and 71.5% of the NT is read in the Ordinary Form. The ‘read the Bible in 3 years’ idea is a myth.”

Index Lectionum

Index Lectionum is the first volume in a proposed series titled

Lectionary Study Aids, by Matthew P. Hazell. The index is a straightforward book of tables that list all the readings from the Old and New Testaments and indicate where they are used in both forms of the Mass. The index does not cover the use of the Bible in liturgies outside of the Mass, except for the blessings and sacramental celebrations found in each Missal.

Matthew Hazell is a convert to Catholicism from evangelical Protestantism who lives in Sheffield England. He is a scholar whose particular interest is in the Roman Catholic liturgical reform of the twentieth century. He maintains a blog about his projects and studies at “Lectionary Study Aids”, [8] which is a good resource for anyone interested in liturgical studies, and he is a contributor to the New Liturgical Movement website at http://newliturgicalmovement.org.

Hazell is preparing a second volume dealing with the Psalms. The planned second volume will include the entrance (introit), offertory, and postcommunion chants and antiphons, as well as the graduals, tracts, alleluias, and responsorial psalms in both forms of the Roman Rite.

Hazell mentioned in his Introduction that he hopes also to create another Index to compare the use of Scriptural and other readings in the Divine Office and Liturgy of the Hours.

An Illustrative Example

The

Index Lectionum is made up of tables with three columns. The first column lists all the verses and pericopes of the Old and New Testaments book by book. (A pericope is a collection of verses that make up a story or a unit of thought.) The middle and left columns indicate where each verse or pericope is included in the liturgical year for both.

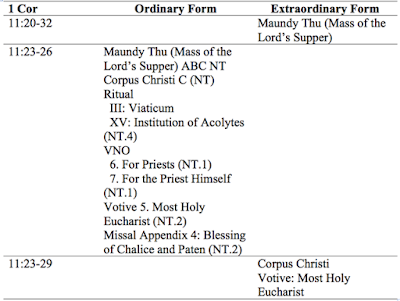

This example excerpt from

Index Lectionum shows how certain significant verses from 1 Corinthians 11 are used and not used in the readings for both forms.

Note: Where a number is shown after NT in the example, it refers to the reading’s place in the ordered list of possible options. So, in the entry for Ritual XV: Institution of Acolytes, NT.4 means the reading is the fourth in a list of options for the New Testament reading that may be chosen for reading in that ritual.

As shown in the excerpt from the

Index Lectionum, the entirety of 1 Corinthians 11:20-32 is read in the Extraordinary form on Maundy Thursday, and verses 23-29 are read on the feast of Corpus Christi and during the Votive Mass of the Most Holy Eucharist. In contrast, the verses show in italics in the passage below (1 Corinthians 11:20-2 and 27-32) are never used in the revised lectionary.

20 Brethren, When you come therefore into one place, it is not now to eat the Lord's supper. 21 For every one taketh before his own supper to eat. And one indeed is hungry and another is drunk. 22 What, have you not houses to eat and to drink in? Or despise ye the church of God and put them to shame that have not? What shall I say to you? Do I praise you? In this I praise you not. 23 For I have received of the Lord that which I also delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus, the same night in which He was betrayed, took bread, 24 And giving thanks, broke and said: Take ye and eat: This is My Body, which shall be delivered for you. This do for the commemoration of Me. 25 In like manner also the chalice, after He had supped, saying: This chalice is the new testament in My Blood. 26 This do ye, as often as you shall drink, for the commemoration of Me. For as often as you shall eat this bread and drink the chalice, you shall show the death of the Lord, until He come. 27 Therefore, whosoever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the Body and the Blood of the Lord. 28 But let a man prove himself; and so let him eat of that bread and drink of the chalice. 29 For he that eateth and drinketh unworthily eateth and drinketh judgment to himself, not discerning the Body of the Lord. 30 Therefore are there many infirm and weak among you: and many sleep. 31 But if we would judge ourselves, we should not be judged. 32 But whilst we are judged, we are chastised by the Lord, that we be not condemned with this world.

A Catholic who attends Extraordinary Form Masses is going to hear all of these verses about receiving the Eucharist worthily at least once a year if he or she attends the Mass on Maundy (Holy) Thursday and will hear most of them on the feast of Corpus Christie, or at a votive Mass of the Most Holy Eucharist. A Catholic who attends Ordinary Form Masses is never going to hear any four of these verses during any of the three year cycles. This omission is one of the many striking details that one can discover by studying the

Index Lectionum.

These verses were probably omitted because they fall under the category of difficult verses, which are mentioned in the General Introduction to the Lectionary in sections 76 and 77:

76. In readings for Sundays and solemnities, texts that present real difficulties are avoided for pastoral reasons. The difficulties may be objective, in that the texts themselves raise profound literary, critical, or exegetical problems; or the difficulties may lie, at least to a certain extent, in the ability of the faithful to understand the texts. 77. .... certain readings of high spiritual value for the faithful [are omitted] because those readings include some verse that is pastorally less useful or that involves truly difficult questions.[9]

It is not my job or my inclination to criticize the revised lectionary. But, on the other hand, it is obvious to me that the deletion of the warning of St. Paul in verses 27-32 of 1 Corinthians 11 is highly significant because the verses are important doctrinally. To give one recent example of a hotly debated moral issue, these verses are an important help in understanding why the Church teaches that divorced and remarried Catholics in an illicit marriage should not receive Communion. (The verses also apply to anyone who is habitually committing the sin of fornication, or cohabiting, supporting abortion, or engaging in any unrepented mortal sin.)

As one blogger at National Catholic Register explained, after quoting the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

“A person who is habitually engaging in sexual relations outside the bonds of marriage (between one man and one woman) is in mortal sin and is not "in a state of grace." St. Paul emphasizes the grave consequences of failure to consider one's spiritual state when going forward to receive Christ in the Eucharist. In 1 Corinthians 11:27, Paul writes: If one eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner, he will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord.” [10]

As another commentator has written, for the Jews to be guilty of someone’s body and blood was to be a murderer. Someone who has never heard 1 Corinthians 11 verses 27 and 30 may think the Church’s prohibition of Communion for those who are living in mortal sin is prejudiced meddling and heartless interference, instead of as a lovingly offered protection against the sinner becoming “guilty of the body and blood of the Lord,” to help keep the sinner from sinning even more gravely by receiving a sacrilegious communion, and from becoming like those “who have become weak and sick and some have even died.”

Interpreting the Differences

In the Foreword, “Not Just More Scripture, But Different Scripture,” Dr. Peter Kwasniewski discusses and interprets the kinds of changes that can be discerned from a close look at the

Index Lectionum. He praises the inclusion of prophetic readings for the weekdays of Advent, the “enrichment” of weekday readings in Pascaltide, and the “occasional felicitous pairing of certain Old Testament and New Testament pericopes that bring out the interrelationships of the covenant.”

Dr. Kwasniewski goes on to point out that there are many deletions of pericopes, and that some of the verses that were traditionally part of the pericopes included in the traditional Mass are deleted.

Dr. Kwasniewski prefers the Extraordinary Form for many reasons, and he is far from neutral in his criticisms of the reformed lectionary. To give just one example of his tone, Dr. Kwasniewski’s interpretation of the rationale behind the omission of 1 Corinthians verses 27-32 is as follows, “The methodical elimination of one of St. Paul’s gravest admonitions plays smoothly into the hands of those who wish to redefine morality from the ground up, and with it sacramental theology.”

You may or may not agree with Dr. Kwasniewski assessment of the motivations behind those who made the changes to the lectionary, but in any case, the Index Lectionum will show you what the changes are, and you may draw your own conclusions.

---------------

[1] Pope Benedict XVI first introduced the terms Ordinary Form and Extraordinary Form in Summorum Pontificum in 2007, to differentiate between the Mass of Pope Blessed Paul VI according the Missal of 1970 (which is often called the Novus Ordo Mass) and the Mass of Pope Saint John XXIII according to the Missal of 1962 (which is often called the Traditional Latin Mass or the Tridentine Mass). In Summorum Pontificum, Pope Benedict affirmed that there are not two Masses in the Roman rite, but two forms of the Roman rite. The Mass of Pope Paul VI is the Ordinary Form, while the Mass of Pope Saint John XXIII is the Extraordinary Form.

[2] Rev. Fr. Brian W. Harrison, “The Biblical Dimension of Paul VI's Liturgical Vision” (Living Tradition: Organ of the Roman Theological Forum) No. 154; PDF. http://www.rtforum.org/lt/lt154.pdf

[3] Other relevant SC sections are:

• § 24: Sacred scripture is of the greatest importance in the celebration of the liturgy. For it is from scripture that lessons are read and explained in the homily, and psalms are sung; the prayers, collects, and liturgical songs are scriptural in their inspiration and their force, and it is from the scriptures that actions and signs derive their meaning. Thus to achieve the restoration, progress, and adaptation of the sacred liturgy, it is essential to promote that warm and living love for scripture to which the venerable tradition of both eastern and western rites gives testimony.

• § 51: The treasures of the bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God's word.

• § 92: Readings from sacred scripture shall be arranged so that the riches of God's word may be easily accessible in more abundant measure.

[4] The lectionary is a book that contains the collection of scripture readings appointed for each day in the liturgical year and for each feast.

[5] The post-Vatican II Roman Missal is usually published in two parts: the Sacramentary (texts and prayers spoken by the priest at the altar or presider's chair, but not including the readings), and the Lectionary for Mass (biblical readings proclaimed from the lectern or ambo). The current USA edition of the lectionary is in four volumes:

• Sundays and Major Feast Days - Years/Cycles A, B, C

• Weekdays, Year I - odd-numbered years, incl. feasts of saints with proper readings

• Weekdays, Year II - even-numbered years, incl. feasts of saints with proper readings

• Common of Saints, Rituals, Votives, Masses for Various Needs and Occasions - many more choices of readings than before

[6] It’s a little known fact, except among cognoscenti in sacred music circles, but the General Instruction of the Roman Missal allows the traditional Gradual to still be recited or sung instead of the Responsorial Psalm before the Gospel in Ordinary Form Masses. One reason why the Gradual is seldom used in the OF is that the Gradual does not appear in the order of the Mass any of the missals; it is available in the Graduale Romanum, which is a separate book that contains music for the Mass, and whose existence is another little-known fact among Roman Catholic church musicians. See also: • “The Real Catholic Songbook” by Jeffrey Tucker at

http://www.catholicity.com/commentary/tucker/03414.html• “A Primer on the Gradual” by Jeffrey Tucker at

http://www.chantcafe.com/2011/04/primer-on-gradual.html[7] “Lectionary Statistics” at the “Catholic Lectionary”

http://catholic-resources.org/Lectionary/Statistics.htm. Links to various editions of the Lectionary and related resources,

see also the Bibliography page.

[8] Matthew Hazell Lectionary Study Aids:

http://catholiclectionary.blogspot.com. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

[9] General Introduction to the Lectionary (Second Edition). Sacred Congregation for the Sacraments and Divine Worship. 21 January, 1981.

[10] “Philly Mayor Attacks Eucharistic Doctrine as ‘Not Christian’” by Kathy Schiffer (

http://www.ncregister.com/blog/kschiffer/philadelphia-mayor-attacks-catholic-belief-on-eucharist-as-not-christian).