No, this article is not a plea for bending and breaking the Church’s matrimonial rules. In fact, it has almost nothing to do with the subject of marriage — except perhaps in a sense to which I will return at the end.

The irregularity to which I refer is none other than the many beautiful differences that characterize the various seasons of the liturgical year in the

usus antiquior. The traditional rubrics, texts, and chants of Lent and Easter bring the contrasting characters of their seasons strongly to the fore: in Lent we suppress the Alleluia while in Paschaltide we sing it repeatedly; the Gloria disappears and then returns with exultation; the Gloria Patri drops away in Passiontide and enters the liturgy anew with Easter. There are many such elements and structures of differentiation, and while the Ordinary Form retains some of them, many, even most, were abandoned.

The traditional Latin Mass and Divine Office display a plethora of differences between seasons as well as on certain special days of the year, be it Ember Days, Rogation Days, All Souls, Candlemas, or what have you. These irregularities or deliberate departures from the “standard” approach magnify the psychological power of the rites and augment their spiritual impact. They also help worshipers enter more deeply into particular mysteries, seasons, or feasts by, on the one hand, startling them out of rote habit, and, on the other hand, building up over the years subliminal associations that reinforce the particular graces besought by the Church at that time.

Three of my favorite distinctive marks take place in Masses around and after Easter. First, there is

the use of the Gradual Haec dies during the entire Octave, albeit with changing verses for each day.[1] The constant refrain in the Mass (and in the Office, too) of “THIS is the day that the Lord has made” strongly reinforces the idea of the Octave as one gigantic celebration, and therefore paves the way to

experiencing it thus. Moreover, the liturgy preserves the important formulation: “exultemus et laetemur

in ea,” let us rejoice and be glad

in it, that is, in this wonderful Day of the Lord, the Dayspring from on high, the New Song, the Risen Christ Himself. The postconciliar translation “Let us rejoice and be glad,” period, sounds like a generic exhortation to be happy. “Let us rejoice and be glad

in it” points us to the object of our rejoicing, the cause of our gladness, which is none other than the Easter mystery itself, in the Person of the ever-living Christ. While the

Haec dies is an option for every day of Easter Week in the Ordinary Form (simply consult the

Graduale Romanum of 1974), it is almost never met with in the wild. When the responsorial psalm of year-round familiarity is chosen, an opportunity is lost — from a textual and structural point of view — for emphasizing the differentness, uniqueness, and unity of the Octave by means of the interlectional psalm.

A second distinctive mark in the

usus antiquior is

the addition of “alleluia” to almost everything: the versicles of Mass and Office (e.g., “V. Ostende nobis…alleluia / R. Et salutare tuum…alleluia”) and all the antiphons at Mass, not to mention the word’s prominence in the

Vidi aquam, the

Regina caeli, and other Paschal chants and hymns. The sequence

Victimae Paschali, which is required to be used every day of the octave, ends with an intense “Amen, alleluia.” Holy Mother Church, the immaculate bride, cannot contain her joy at the resurrection of her Lord, and sings this word of jubilation whenever and wherever she can. Again, it makes a difference that these numerous Alleluias are required to be said or sung in the

usus antiquior, whereas they are rarely exercised options in the Ordinary Form. The

usus antiquior pours forth a joyous flood of alleluias — indeed, like water flowing from the temple — enacting with potent literalness the well-known line from St. Augustine, “we are an Easter people and Alleluia is our song.”

This brings me to a third distinctive mark of the ancient Roman liturgy in Easter season, and my personal favorite:

the use of a double Alleluia before the Gospel during the weeks of Paschaltide. When the priest or subdeacon finishes chanting the Epistle, the Schola begins to sing — not a Gradual as throughout the year, nor a Tract as in Lent, but a special Alleluia with a verse of its own, followed by another Alleluia and verse, both drawing more heavily than usual upon New Testament texts (e.g., Mt 28:7 and Jn 20:26 on Low Sunday, Lk 24:35 on Good Shepherd Sunday, Lk 24:46 on the Third Sunday after Easter, etc.). The chanted alleluias for the Sundays after Pentecost are already lavish in their contemplative splendor; add

another of the same character, and you are starting to swim in the shallows of the Eighth Day. There is a kind of suspension of time and place in these great Paschal alleluias, as if one would wish to linger forever in the more-than-mortal joy of the Resurrection, in the sober inebriation of the Spirit, remembering and resting in the victory of our King, before resuming the fight against the world, the flesh, and the devil.

Traditionally, the Gradual, Tract, and Alleluia are all fairly lengthy interlectional chants, written in a melismatic style for the sake of meditating on the Word of God, allowing it to soak in, and preparing the ground for the Gospel as by the application of a long, slow dripline. Although the twin chanted Alleluias are an option in the Ordinary Form (see once more the

Graduale Romanum of 1974), they are rarely used, for two simple reasons. First, in the reformed liturgy, the Responsorial Psalm was introduced as an opportunity for verbal participation and the Alleluia changed into a short and easily-repeatable acclamation that rouses people to stand for the Gospel. In this way the historic character and liturgical function of the interlectional chants were fundamentally altered, and with them, the requisite aesthetic forms. If the expectation is that people will speak or sing the psalm and the alleluia (and stand up for the latter), it is obvious that two melismatic Alleluias back to back will not serve the purpose. Of course, this is not to say that Alleluia acclamations cannot be done beautifully—my own choir, when assisting at the Ordinary Form, sings either a Bach setting or a Mozart setting at this juncture, either of which comes across nobly—but we must recognize that we are dealing with a different thing from what the Alleluia had been for most of the history of the liturgy.[2]

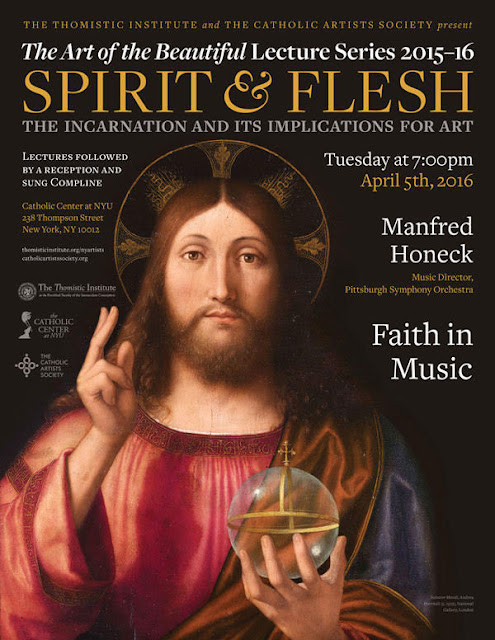

![]() |

| The double Alleluia from the Fourth Sunday after Easter (EF) |

In the traditional Latin Mass, such beautiful Paschal “touches” or “flourishes” are built into the liturgy itself, and no choice is given about whether to exercise them or not. It offers us a privileged spiritual freedom of experiencing more sharply, more

actively, the mysteries of the Lord by demanding of us that we modify certain musical habits, adjust our singing and praying according to the seasons, and in all things submit ourselves to a certain cosmic and sacramental rhythm that is far greater than ourselves and our generation.

The foregoing examples (and there are more as we range across the liturgical year and its celebrations — particular during Holy Week) show how, in the name of a certain drive towards simplification and ease of access, some of the inner riches, one might even say the well-regulated irregularities, of the sacred liturgy were lost. As Catherine Pickstock has pointed out, it is ironic that on the cusp of postmodernity and its (at least purported) appreciation for otherness, difference, and pluralism, institutional choices valorized sameness, uniformity, standardization. This is certainly one legacy that the recovery of the

usus antiquior can help the Church to move decisively beyond, as we seek to reconnect with the history and anthropology of Catholic worship. Thus, learning about the origin and meaning of special Paschal elements in the

usus antiquior will awaken clergy and musicians to the desirability of exercising them in the Ordinary Form as the permissible and choiceworthy options they are, in this way not only rebuilding fallen bridges between old and new, but, more importantly, offering Catholics today a more intense and memorable experience of the bright victory of Easter.

I said at the start that this post had little to do with marriage, but there is one parallel worth pointing out. In a healthy marriage, the spouses make an effort to do things that are out of the ordinary for one another. On special occasions like anniversaries or birthdays, flowers or chocolates may enter the home, or the couple may go out on a date. Married people do this sort of thing because they know that a uniform monotonous routine, which takes too much for granted, is a recipe for mental and emotional stagnation. They know, in other words, that sometimes the best rule is to have a certain irregularity. Christ’s beautiful Bride, the Church, has known and lived the same secret: her liturgical traditions are the evidence. It will be wise for us to know and live this secret, too.

NOTES[1] The Roman liturgy is fairly austere and reserved in its Easter celebrations as compared with the Eastern rites or even the other medieval Western rites (as Gregory DiPippo recently discussed

in connection with Vespers), and yet it still has its own treasures that must not be allowed to vanish owing to the pressure of "market forces." An example would be the distinctive sections of the Roman Canon for Easter week, which, of course, are printed in the OF altar missal, but will be heard only by those fortunate enough to have a priest who chooses the venerable Roman Canon during the Octave.

[2] For discussion of the meaning and importance of interlectional chants, see William Mahrt’s

The Musical Shape of the Liturgy.