Like the prayers before the altar at the beginning of Mass and the priest’s communion prayers, the Offertory prayers are a medieval addition to the Order of the Mass, one of the many ways in which the Church has enriched the center of Her prayer life. In all three of these additions, there is a great deal of variety to be found between the different Uses of the Roman Rite; this series will continue by examining the various forms of the Offertory prayers and the rites that accompany them. It is not my intention to be exhaustive, of course, but merely to present a selection of some of the more widely used and interesting texts. I will begin with those of the three non-monastic religious orders which maintained their own proper uses after the Council of Trent and until the post-Conciliar liturgical reform.

(In these descriptions, the incensing at the Offertory will for the most part be omitted, partly because it is not especially important to the specific topic of the series, partly because there is no description of it in many of the missals of the medieval Uses. The term “medieval” here is used in reference to Uses of the Roman Rite that trace their origins to the Middle Ages, even though the printed sources out of which I will describe them are post-Medieval.)

Two fundamental texts

First of all, we must make note of two texts which occur in the great majority of Offertory Rites. One is the prayer

Suscipe sancta Trinitas, which first appears in the basic form used throughout the Middle Ages in the Sacramentary of Echternach, written in the year 895; it occurs with variants in the great majority of medieval Uses.

Suscipe, sancta Trinitas, quam tibi offero in memoriam Incarnationis, Nativitatis, Passionis, Resurrectionis, Ascensionisque Domini nostri Jesu Christi, et in honore omnium Sanctorum tuorum, qui tibi ab initio mundi placuerunt, et quorum hodie festivitates celebrantur, et quorum hic nomina et reliquiae habentur, ut illis proficiat ad honorem, nobis ad salutem, quatinus illi omnes pro nobis intercedere dignentur in caelis, quorum memoriam facimus in terris.

Receive, o holy Trinity, this offering, which I offer to Thee in memory of the Incarnation, Birth, Passion, Resurrection and Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ, and in honor of all the Saints who have pleased you from the beginning of the world, and whose feasts are celebrated today, and whose names and relics are kept here; that it may profit unto their honor and our salvation; that all those whose memory we keep on earth, may deign to intercede for us in Heaven.

The second is the prayer

In spiritu humilitatis, which I give here in the form used in the Roman Missal of St. Pius V. The medieval variants in this texts are usually no more than small differences in the order of the words.

In spiritu humilitatis, et in animo contrito suscipiamur a Te, Domine: et sic fiat sacrificium nostrum in conspectu Tuo hodie, ut placeat Tibi, Domine Deus. - In a spirit of humility, and in contrite heart, may we be received by Thee, o Lord; and so may our sacrifice take place in Thy sight this day, that it may please Thee, o Lord.

The Dominican Use

In the Dominican Missal, as in many other medieval Uses, the chalice is prepared before the Mass begins. The priest pours wine into the chalice, and then the server offers him the cruet with the water and says “Benedicite”. (“Bless” in the imperative.) The priest makes the sign of the Cross once over the water, saying “In nomine Patris et Filii

+ et Spiritus Sancti. Amen.”, and pours a small amount of water into the chalice as in the Roman Rite. The chalice is then covered with the pall and veil.

At the Offertory, the priest uncovers the chalice, then lifts and closes his hands as he says the words of Psalm 115, “What shall I render to the Lord, for all the things he hath rendered unto me? I will take the chalice of salvation; and I will call upon the name of the Lord” He then lifts the chalice, together with the paten and host that rest on top of it, saying the following prayer, a much simplified version of

Suscipe, sancta Trinitas.

Suscipe, sancta Trinitas, hanc oblationem, quam tibi offero in memoriam passionis Domini nostri Jesu Christi; et præsta ut in conspectu tuo tibi placens ascendat, et meam et omnium fidelium salutem operetur æternam.

Receive, o Holy Trinity, this offering, which I offer to Thee in memory of the passion of our Lord, Jesus Christ; and grant that in Thy sight it may be pleasing and ascend to Thee, and effect my eternal salvation and that of all the faithful.

After laying the host on the corporal, he washes his fingers, saying only three verses of Psalm 25, where the Roman Rite has seven and the doxology. “I will wash my hands among the innocent; and will compass thy altar, O Lord: that I may hear the voice of thy praise: and tell of all thy wondrous works. I have loved, O Lord, the beauty of thy house; and the place where thy glory dwelleth.” He then returns to the middle of the altar, and bowing lay says the Dominican version of

In spiritu humilitatis, with the addition noted in bold type.

In a spirit of humility, and in contrite heart, may we be received by Thee, o Lord; and so may our sacrifice take place in Thy sight this day, that it may be received by Thee, and please Thee, o Lord.

Turning to the people, he then says “Orate, fratres: ut meum ac vestrum pariter in conspectu Domini sit acceptum sacrificium. – Pray, brethren, that my sacrifice, which is equally yours, may be accepted in the sight of the Lord.” As in a number of medieval uses, no response is made to the

Orate fratres. Before the Secret, the priest adds “Hear, o Lord, my prayer: and let my cry come to thee. Let us pray.”

Here we must note in particular the presence in the

Orate fratres of the word “pariter – equally”, an adverb modifying the word “vestrum”, to express the union of the faithful with the priest in the offering of the Eucharistic sacrifice. This is a variant common to a number of medieval Uses, including the two which follow here, those of the Carmelites of the Old Observance and the Premonstratensians.

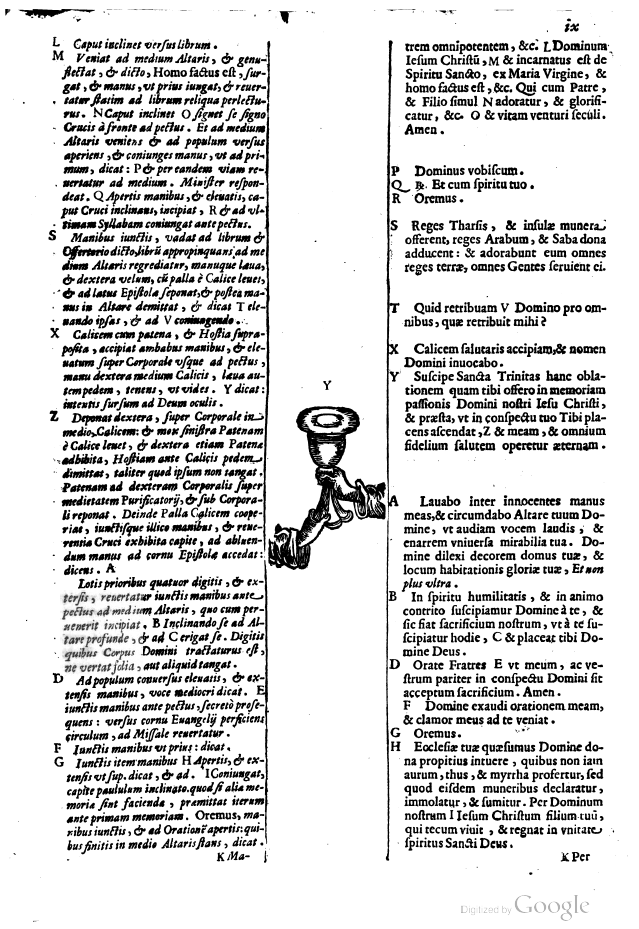

![]() |

| A page of the Ritus servandus of a Dominican Missal from 1687, explaining the Offertory ritual. (available on googlebooks) |

The Old Carmelite Use

The traditional Use of the Carmelite Order derives from that of the Latin Rite canons installed in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem at the time of the Crusades. As such, it is, like the Dominican Use, a tradition whose earliest roots lie in France; the Carmelites Offertory, however, is longer and more complex than that of the Dominicans. (In 1584, the Discalced Carmelites, as part of the process of separating themselves from the Old Observance, passed over to the use of the Roman books.)

The chalice is prepared before the Mass, as noted above in the Dominican Use. After saying the Offertory antiphon, the priest uncovers the chalice, then makes the sign of the Cross over the chalice and host, saying “In nomine Patris etc.” He then lifts them all together with both hands, “raising his eyes to God”, as the rubric says, “and with devout mind” says the Carmelite version of Suscipe, sancta Trinitas.

Suscipe, sancta Trinitas, hanc oblationem, quam tibi offerimus in commemorationem Incarnationis, Nativitatis, Passionis, Resurrectionis Ascensionisque Domini nostri Jesu Christi: et adventus Spiritus Sancti, et in honore beatæ et gloriosæ Dei Genitricis semperque Virginis Mariæ, et omnium sanctorum tuorum, qui tibi placuerunt ab initio mundi; et pro salute vivorum et requiem omnium fidelium defunctorum.

Receive, o holy Trinity, this offering, which we offer to Thee in commemoration of the Incarnation, Birth, Passion, Resurrection and Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ, and of the coming of the Holy Spirit, and in honor of the blessed and glorious Mother of God and ever-Virgin Mary, and of all the Saints who have pleased you from the beginning of the world, and for the salvation of the living, and the rest of all the faithful departed.

The priest lays the chalice and host on the corporal, and arranges the paten, the pall and the purificator in their places. He then lifts his eyes, opens and closes his hands, bows, and makes the sign of the Cross once again over the host and chalice saying, “Benedictio Dei omnipotentis, Patris et Filii

+ et Spiritus Sancti, descendat super hanc oblationem, et maneat semper. – May the blessing of Almighty God, the Father, Son

+ and Holy Spirit, come down upon this offering and abide forever.”

There follows the washing of the fingers, with the same verses of Psalm 25 and as in the Roman Missal. Returning to the middle of the altar, he once lifts his eyes, opens and closes his hands, and bows, saying

In spiritu humilitatis as in the Dominican Use (with a slight difference in word order). He then makes the sign of the Cross over himself.

The

Orate fratres reads as follows: “Orate pro me, fratres: ut meum pariter et vestrum Deo sit acceptabile sacrificium – Pray for me, brethren, that my sacrifice, which is equally yours, may be acceptable to God.” An edition of the Carmelite Missal printed at Brescia, Italy, in 1490 indicates no response, but pre-Tridentine missals are sometimes rather imprecise. In the 1621 edition printed at Venice, a response is given, words of Psalm 19, “May the Lord be mindful of all thy sacrifices: and may thy whole burnt offering be made fat. May he give thee according to thy own heart; and confirm all thy counsels.” (A similar response was given in the Use of York in England.) The priest then says “Hear O Lord... Let us pray.” as noted above in the Dominican Use, before the Secret.

![]() |

| The frontispiece of a Carmelite Missal printed in 1621, showing the lamentable habit of updating liturgical books in ink. (available on googlebooks) |

The Premonstratensian Use

Shortly after the Council of Trent, the Abbot of Prémontré, Jean des Pruets, elected in 1572, ordered the publication of a new edition of the order’s Missal. This edition, printed six years later in Paris, remained closely faithful to the pre-Tridentine customs of the Order, retaining the medieval form of the Offertory, and, inter alia, a large corpus of sequences and proper votive Masses. In 1622, however, under Abbot Pierre Gosset, the Missal was heavily Romanized; most of the sequences were suppressed, and both the corpus of votive Masses and the Offertory assimilated to that of the Roman Missal. Here I shall give the text of the 1578 des Pruets edition, which, however, contains no

Ritus servandus, (the general rubric on how to say the Mass), and is rather sparse on rubrics generally. (More recent Premonstratensian liturgical books go quite far in the opposite direction.)

When pouring water into the chalice, the priest says “Fiat hæc commixtio vini et aquæ pariter in nomine Domini nostri Jesu Christi, de cujus latere exivit sanguis et aqua. – May this mingling of water and wine together be done in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, from whose side there came forth blood and water.” This reference to the blood and water that flowed from Christ’s side, as recounted in John 19, 34, is found in other missals as well, such as those the Ambrosian Rite and the Carthusians.

The rubric that follows says “While the host and chalice are offered”, but it is not specified how. The words said here are “Panem cælestem

+ et calicem

+ salutaris accipiam, et nomen Domini invocabo. – I will take up the bread of heaven and the chalice of salvation, and call upon the name of the Lord.” Presumably he makes the sign of the Cross over them at the places marked. After the chalice has been covered, the priest says, “Veni, invisibilis sanctificator; sanctifica hoc sacrificum tibi praeparatum. – Come, invisible Sanctifier; sanctify this sacrifice prepared unto Thee.”

Bowing before the altar, he then says the

Suscipe sancta Trinitas as follows.

Suscipe, sancta Trinitas, hanc oblationem, quam tibi offerimus in memoriam passionis, resurrectionis et ascensionis Domini nostri Jesu Christi: et in honorem beatæ Mariæ semper Virginis, et sancti Joannis Baptistæ, et omnium cælestium virtutum, et omnium sanctorum qui tibi placuerunt ab initio mundi; ut illis proficiat ad honorem, nobis autem ad salutem: et ut illi omnes pro nobis et pro cunctis fidelibus vivis et defunctis orare dignentur in cælis, quorum memoriam facimus in terris. Qui vivis et regnas in sæcula sæculorum. Amen.

Receive, o holy Trinity, this offering, which we offer to Thee in memory of the Passion, Resurrection and Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ, and in honor of the blessed Mary ever-Virgin, and of Saint John the Baptist, and all of the heavenly powers, of all the Saints who have pleased you from the beginning of the world, that it may profit unto their honor, and to our salvation; and that all those whose memory we keep on earth, may deign to pray in Heaven for us and for all the faithful, living and deceased. That livest and reignest for ever and ever. Amen.

In spiritu humilitatis is not said. The

Orate fratres is labelled in the rubric “The priest’s supplication to the people.” “Orate, fratres, pro me peccatore: ut meum pariter ac vestrum in conspectu Domini sit acceptum sacrificium. – Pray for me, a sinner, brethren, that my sacrifice, which is equally yours, may be accepted in the sight of the Lord.” The people’s response begins with words taken from the prayer by which the celebrant blesses the deacon before he sings the Gospel. “Dominus sit in corde tuo et in ore tuo; suscipiatque Dominus Deus de manibus tuis sacrificium istud, et orationes tuæ ascendant in memoriam ante Deum pro nostra et totius populi salute. – May the Lord be in thy heart and in thy mouth, and may the Lord God receive this sacrifice from thy hands, and may thy prayers ascend in remembrance before God, for our salvation and that of all the people.”

The same

Orate fratres and response to it are found in the Use of the Cistercians, an order contemporary with the Premonstratensian; the offertory of the Cistercian and Carthusian Missals will be described in the next article in this series.

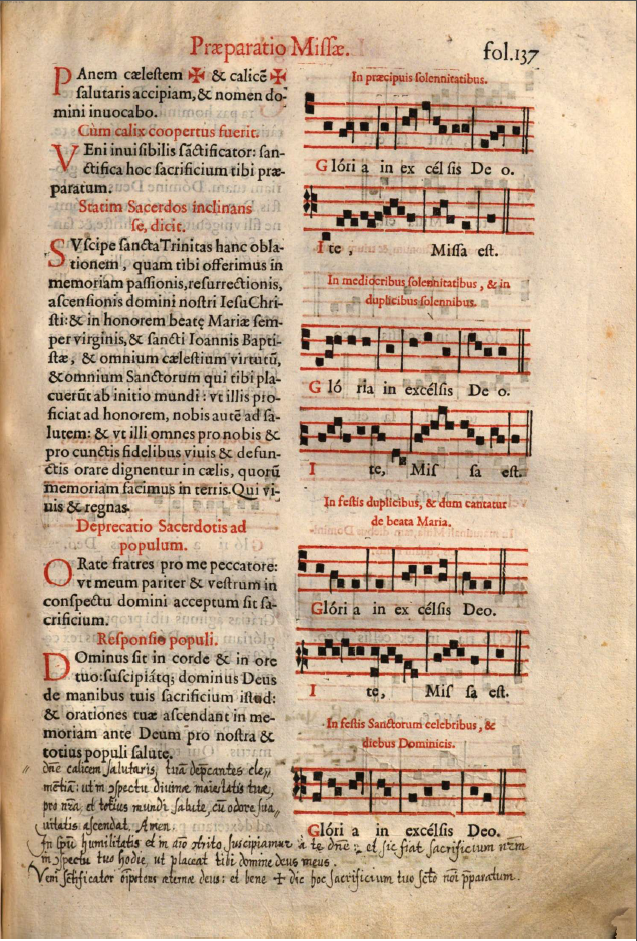

![]() |

| A page of the 1578 Premonstratensian Missal. The Offertory prayers are on the left side, and various intonations of the Gloria, with the corresponding Ite, missa est, on the right. Pre-modern liturgical books were often printed with a surprising lack of logic in ordering the material. At the bottom, the Roman Offertory prayers were written in after the Romanization of the Premonstratensian liturgical books (in ink, again.) |

.jpg)