The joint commemoration of the Apostles Peter and Paul is one of the most ancient customs of the Roman Church, attested already in the oldest surviving Roman liturgical calendar, the

Depositio martyrum, written in 336 A.D. A verse of the hymn

Apostolorum passio, agreed by most authorities to be an authentic work of St Ambrose († 397), and still used in the Ambrosian liturgy, says that “the thick crowds make their way through the circuit of so great a city; the feast of the sacred martyrs is celebrated on three streets.” These “three streets” are the via Cornelia, the main street running up to and over the Vatican hill; the via Ostiensis, where the burial and church of St Paul are; and the via Appia, on which sits the cemetery “in Catacumbas”.

This last is the ancient Christian cemetery now called the Catacomb of St Sebastian; the word “catacomb” was in fact originally the name of the site of this cemetery specifically, and only later came to be used as a generic term for ancient subterranean Christian burial grounds. The basilica over the cemetery, now also entitled to St Sebastian, was originally known as the “Basilica Apostolorum”, in memory of a tradition that the bones of Peter and Paul were kept there for a time, probably to save them from destruction in the era of persecutions. This is referred to in various ancient sources, including the

Depositio martyrum, and confirmed by modern archeological research. The celebration of the feast “on three streets” would refer then to a procession to visit the site of St Peter’s burial at the Vatican, that of St Paul on the via Ostiensis, and the cemetery where their remains were once kept.

![]() |

| The building of which this wall is a part was constructed over the Catacomb of St Sebastian about 250 A.D., and is covered with dozens of devotional graffiti like the one seen here. “Paule ed (et) Petre, petite pro Victore - Paul and Peter, pray (lit. ‘ask’) for Victor.” |

The poet Prudentius, writing in the very early fifth century, calls the day “bifestum – a double feast”, and attests that on that day the Pope would say a Mass at the Basilica of St Peter, and then hasten to say another at St Paul’s. He does not refer to a visit to the Catacombs on the via Appia, but assuming this visit was made on the way back to the Papal residence at the Lateran, the total circuit is nearly nine-and-half miles, to be made at the height of the Italian summer. However, only seven years after Prudentius visited Rome in 403, the city was sacked by the Goths, then sacked again by the Vandals in 455; over the sixth and seventh centuries, it was largely reduced to ruins and depopulated by the long wars between the Goths and Byzantines, and the invasion of the Lombards.

It should not be surprising, then, that at a certain point the double feast was divided, and kept in a more manageable way as two separate feasts. In the Gelasian Sacramentary, we find three Masses of Ss Peter and Paul assigned to June 29th; the oldest copy of the Gelasianum dates to roughly 750, but much of the material is considerably older, some of it reaching back even to the days of St Leo the Great 300 years earlier. In some manuscripts, however, one of the three, “the proper Mass of St Paul”, has already been assigned to June 30th. In the Gregorian Sacramentary, written roughly a century later, we find the feast of St Peter on June 29th, and that of St Paul on the 30th; each Mass contains references to the other Apostle, but they are nevertheless clearly distinct. Thus, by the time of Charlemagne, the “bifestum” of Prudentius had already been separated into a two day feast.

At the traditional Mass of June 29th, the majority of the texts refer either to St Peter alone (Introit, Epistle, Alleluia, Gospel, Communion) or to Apostles generically, as in the Gradual “Thou shalt make them princes over all the earth.” The sole reference to St Paul is in the Collect, “O God, who hast consecrated this day by the martyrdom of Thy Apostles Peter and Paul, grant Thy Church to follow in all things the teaching of those through whom she first received the faith.” The Office is likewise dedicated almost entirely to St Peter, the notable exceptions being the hymns of Vespers and Lauds, and the antiphon of the Magnificat at Second Vespers. This latter is in both the structure of its text and in its Gregorian melody very similar to the Magnificat antiphon at Second Vespers of Pentecost, to indicate that the mission of the Holy Spirit is fulfilled in the lives and deaths of the Apostles, and thereafter in their successors.

Ant. Hodie * Simon Petrus ascendit crucis patibulum, alleluia: hodie clavicularius regni gaudens migravit ad Christum: hodie Paulus Apostolus, lumen orbis terrae inclinato capite pro Christi nomine martyrio coronatus est, alleluia.

On this day, Simon Peter ascended the gibbet of the cross, alleluia: on this day, he that beareth the keys of the kingdom of heaven passed rejoicing to Christ: on this day, Paul the Apostle, the light of the world, inclining his head, for the name of Christ was crowned with martyrdom, alleluia.

The following day, therefore, the whole of the liturgy is dedicated to St Paul, and is not called a day within the octave of the Apostles, but rather “the Commemoration of St Paul.” The variable texts of the Mass all refer to him, but a commemoration of St Peter is added to the feast, in accordance with the tradition that the two are never entirely separated in the veneration paid them by the Church. (The same is done on the feast of St Paul’s Conversion, and commemorations of him are added to the feasts of St Peter’s Chairs and Chains.) The Office is likewise dedicated entirely to him; both the Mass and Office, however, make use of St Paul’s own testimony in Galatians 2 to the mission of the two Apostles: “For he who worked in Peter for the apostleship of the circumcision, worked in me also among the gentiles; and they knew the grace of God that was given to me.” In the 1130s, a canon of St Peter’s Basilica named Benedict writes that it was still the custom in his time for the Pope to keep the feast of St Peter at the Vatican, but then celebrate Vespers at the tomb of St Paul in the great Basilica on the Ostian Way, “with all the choirs” of the city.

![]() |

| The apsidal mosaic of the St Paul’s Outside-the-Walls, executed in the 1220s, and heavily repaired after most of the ancient church was destroyed by fire in 1823. To the left of Christ are St Luke and St Paul, on the right St Peter and his brother St Andrew. |

Originally, the Gospel for the feast was St Matthew 19, 27-29, and from this passage are taken the antiphon of the Benedictus and the Communion of the Mass. This same Gospel is used on several other feasts of Apostles, including the days within the octave of Ss Peter and Paul, and the feast of St Paul’s Conversion. It was changed in the Tridentine liturgical reform to St Matthew 10, 16-22, evidently because of the words “you shall be brought before governors, and before kings for my sake, for a testimony to them and to the gentiles,” an eminently appropriate choice for this feast. It also used on the feast of St Barnabas, who, after Paul’s conversion, when the members of the Church feared that it was perhaps a ruse to further the persecution, “took him, and brought him to the Apostles, and told them how he had seen the Lord, and that he had spoken to him.” (Acts 9, 27) The Epistle of the Mass, Galatians 1, 11-20, has been added to the traditional readings for the vigil of Ss Peter and Paul as the Epistle of the vigil Mass in the new rite.

![]() |

| The Apostles Paul and Barnabas at Lystra (Acts 14, 5-18), by Jacob Jordaens, 1645; Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna |

The liturgical tradition of Milan was not formed in reference to the Roman Basilicas and the tombs of the Apostles, and never adopted the Commemoration of St Paul. Both the Mass and Office of June 29th in the Ambrosian Rite give more space to St Peter, often referring to him without mentioning Paul, and elsewhere referring to them both, but never to Paul alone, with the sole exception of the Epistle of the Mass. The first reading is the same as that of the Roman Rite, Acts 12, 1-11, telling of the liberation of Peter from prison in Jerusalem; the Gospel is that of the Roman vigil, John 21, 15-19, in which Christ prophesies the manner of his death. The Epistle between them is the Roman Epistle of Sexagesima Sunday, on which the Roman Station is kept at the Basilica of St Paul. This is Saint Paul’s apologia for his status as an Apostle in Second Corinthians; the church of Milan adds two verses to the beginning of the longest Sunday Epistle of the year from the Roman lectionary. (2 Cor. 11, 16 – 12, 9) The Ambrosian Preface, however, beautifully redresses this inequality.

Truly it is fitting and just, right profitable to salvation to give Thee thanks always, here and everywhere, in honor of the Apostles Peter and Paul. Whom Thy election did so deign to consecrate, that it might change blessed Peter’s worldly trade as a fisherman into divine teaching; so that he might deliver the human race from the depths of hell with the nets of Thy precepts. And then Thou didst change the mind of his fellow Apostle Paul, along with his name; and whom the Church at first feared as a persecutor, She now rejoices to hold as the teacher of divine commandments. Paul was blinded that he might see; Peter denied, that he might believe. To the one Thou gave the keys of the kingdom of heaven, to the other, knowledge of the divine law, that he might call the nations; for the latter brought them in, as the other opened (the door of heaven). Therefore both received the rewards of eternal virtue.

In the Novus Ordo, the Commemoration of St Paul has been abolished, and the texts of both Mass and Office for June 29th rewritten to give equal space to both Apostles. So for example, of the two responsories in the Office of Readings, the first refers to Peter, and the second to Paul. (Inexplicably and unjustifiably, the Magnificat antiphon “Hodie” cited above was not retained.) June 30th is now the feast of the “Protomartyrs of the Roman Church”, the Christians whose martyrdom at the hands of the Emperor Nero is described in a famous passage of the Annals of Tacitus.

But all human efforts … did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration (which destroyed much of Rome in July of 64 A.D.) was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their center and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed. (Book XV, chapter 44)

![]() |

| The Torches of Nero, by Henryk Siemiradzki, 1876 |

Despite the early and explicit attestation of this martyrdom by an historian with no bias in favor of the Christians, there is no historical tradition of devotion to this group of martyrs “whose number and names are known only to God”, as we read in Donald Attwater’s revision of

Butler’s Lives of the Saints. A notice of them was added to the Roman Martyrology in the post-Tridentine revision of Cardinal Baronius, but their feast was not added to the calendar of the diocese of Rome until the early 20th century, by Pope Benedict XV.

The “circus” to which Tacitus refers as the site of the martyrdom was a chariot racing facility that sat immediately to the south of the via Cornelia, next to where St Peter’s Basilica is today. It was allowed to fall to ruins after the death of Nero, and apparently razed to the ground by Constantine to make space for the original basilica. Left in place, however, was the Egyptian obelisk brought to Rome by Caligula, and set up on the “spine” of the circus, as the Romans called it, the wall down the middle around which the chariots raced. The turning posts on the end are called “metae” in Latin, and the apocryphal Acts of Peter, a work of the mid-2nd century, say that Peter was crucified “inter metas”; the obelisk, then, would have been among the last things St Peter saw in this world. After sitting next to the old Basilica for over 12 centuries, it was moved in 1586 to the area in front of the new church, then still under construction, later to be surrounded by Bernini’s Piazza. Its former location is marked by a plaque in the ground to the side of the modern basilica; the surrounding area was renamed by Benedict XV “Piazza of the First Martyrs of Rome.”

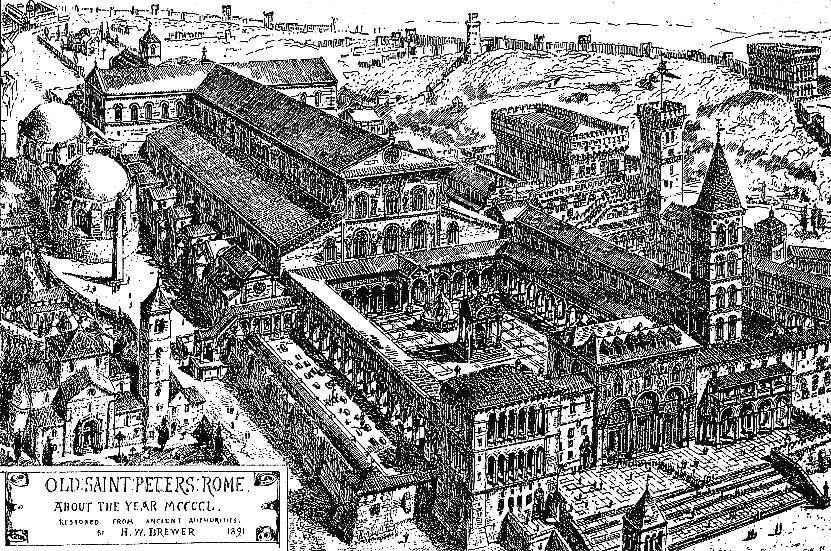

![]() |

| The Basilica of St Peter in 1450, according to the reconstruction of H.W. Brewer, 1891. The obelisk is seen immediately in front of the first rotunda on the left side of the basilica. |

Gratias quam maximas refero Bono Homini, quo sagacior et diligentior consulendus non invenitur!